By Ben Winger

Linked paper: Migration distance is a fundamental axis of the slow-fast continuum of life history in boreal birds by Benjamin M. Winger and Teresa M. Pegan, Ornithology

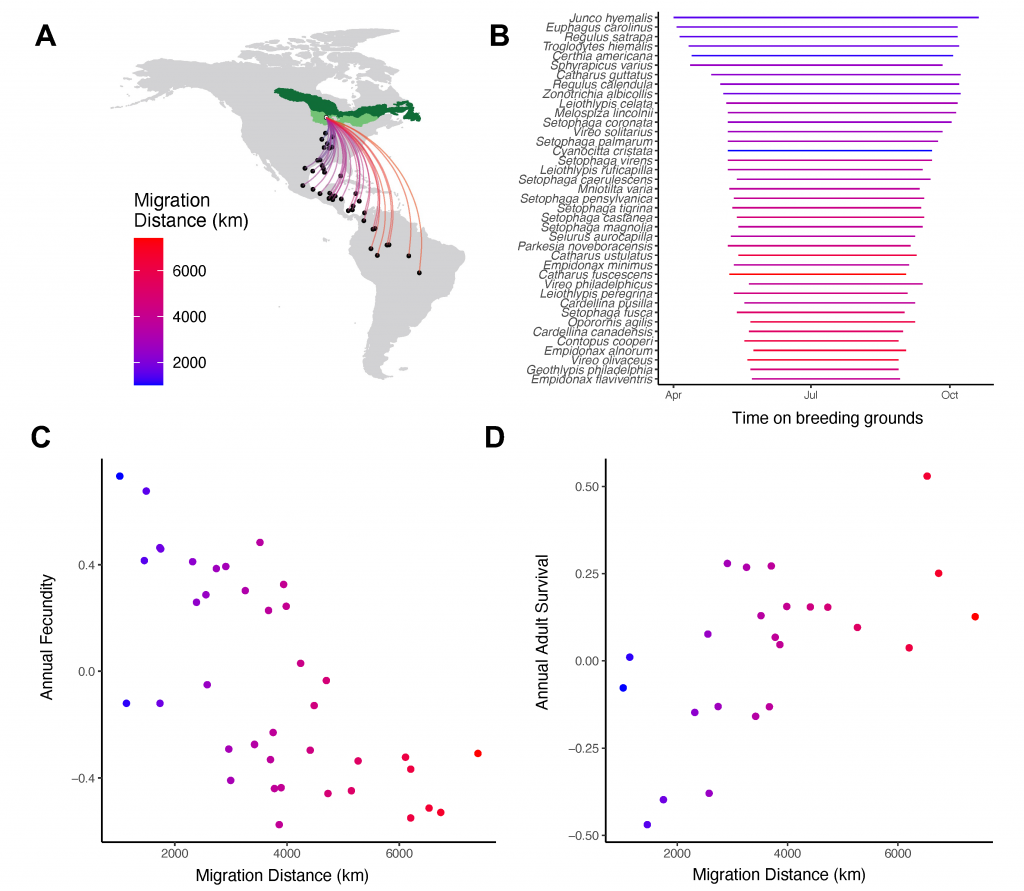

Recently, it occurred to me that the anticipation and excitement of my first spring migration—experienced more than twenty years ago—continues to inspire my research today, including for a new paper on the life history evolution of migratory birds co-authored with Teresa Pegan, a Ph.D. student in my lab at University of Michigan. In our paper, “Migration distance is a fundamental axis of the slow-fast continuum of life history in boreal birds,” which is published in Ornithology this week, we show that the staggered phenology of migration—wherein the longest-distance migrants spend the least amount of time on their breeding grounds—is intimately connected to broadly important life history tradeoffs in 45 species of boreal birds.

For the past decade, I have been conducting research on boreal birds almost every summer, along with a great team of collaborators and students. Our focus has been on collecting genetic samples and specimens to support a variety of interconnected research projects on the evolutionary ecology of migratory birds. Most of our ongoing data collection paused due to the COVID-19 pandemic, so we tried to learn what we could about our study species from a rich multitude of published datasets.

In many ways, this paper was a “pandemic project”—a backburner idea that came to the forefront when our normal activities were shut down in 2020. However, it turns out that the original inspiration for this study came early in my birdwatching years, back when I was in middle school and growing up on the south shore of Lake Erie in Ohio. In the months leading up to that first spring migration, I had spent the better part of the frozen Cleveland winter poring over field guides to learn about all the colorful songbirds that would begin arriving in April. As winter turned to spring, I ventured daily to my local park, before or after school, hoping to see new arrivals. I was thrilled to spot my “lifer” Yellow-rumped Warblers and Ruby-crowned Kinglets on April 8. In the coming days, Black-throated Green and Palm Warblers eventually showed up, all passing through on their way to breeding grounds in boreal forests further north. But by late April, I was growing impatient—where were the charismatic Blackburnian and Mourning Warblers I had marveled at in the books?

My retired birding friend, Bob, told me to wait another week or two; that these species were coming from a long way away and wouldn’t arrive in our patch until May. This was my first lesson in the phenology of bird migration: In many places, the species that migrate the furthest arrive on their breeding grounds later than species that migrate shorter distances. I was surprised to learn a few months later that the inverse is true with autumn migration: I saw Blackburnian Warblers again that year starting in mid-August as they passed south on their way to the Andes, but Yellow-rumped Warblers, who have a much shorter journey, mostly didn’t appear in Cleveland until almost a month later.

Birdwatchers and migration researchers come to know these patterns as the predictable-but-always-exciting drumbeat of migration. But why does such profound variation in phenology exist, and what can it teach us about the evolution of bird migration? The implication is that in these boreal-breeding birds, the species that winter near the equator have shorter breeding seasons than species that winter in more temperate latitudes. By looking at the published data on breeding biology, Teresa and I show that the lengthier breeding seasons of short-distance migrants like Yellow-rumped Warblers occasionally allow these species to raise more broods than long-distance migrants like Blackburnian Warblers, increasing their annual reproductive output. This result is not terribly interesting on its own, but life history theory predicts that higher annual reproductive output should trade off with lower annual survival. This would imply a phenomenon wherein the long-distance migrants should have higher annual survival than species that migrate shorter distances. Such a pattern might seem unlikely. After all, isn’t migration a costly endeavor that carries a high mortality risk? Using data from the Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship project, we were excited to find that migration distance in boreal birds is, indeed, positively correlated with rates of annual adult survival.

Though counterintuitive at first, we argue that higher survival in long-distance versus short-distance migrants makes quite a bit of ecological and evolutionary sense and is consistent with a variety of other recent research on bird migration. In brief, birds that migrate long distances are really good at it—because they have to be. Owing to their shorter breeding seasons and low fecundity, long-distance migrants must have high survival. Another way to look at this pattern is that long-distance migration confers high survival by bringing species to places where they can survive better during the winter, an idea we explore by assessing the climates experienced by migratory species in the winter. By contrast, boreal birds that winter closer to their breeding grounds seem to suffer higher annual mortality, but their populations likely accommodate this through higher annual fecundity. That is, despite the intense pace of migration, long-distance migrants seem to have “slower” life histories than short-distance migrants.

Going forward, some of the main follow-up questions we hope to study in this system include assessing how the spectrum of migratory distance and breeding phenology influences dispersal and gene flow, and also to test whether the life history differences we observe in long- versus short-distance migrants predict patterns of molecular evolution that also vary on the slow-fast continuum. Teresa is investigating both topics for her Ph.D. dissertation, and will be giving a talk on migration and molecular evolution at the upcoming AOS & SCO-SOC 2021 Virtual Meeting!

COMMENTS