Most of my birder friends don’t do much birding in the summer unless they are involved in breeding bird surveys. Once the flush of spring migration, Global Big Days, and the frenzy of territory establishment have passed, most of them spend the summer months from mid-June to mid-August catching up on their reading, bringing their e-bird lists up-to-date, and planning birding trips for the fall.

It wasn’t always like this. For many bird enthusiasts, the summer months were the most exciting, because that’s when birds were nesting and egg-collecting was an all-consuming hobby. Even as recently as the 1970s, my old friend George Peck [1] and I spent most of our summer weekends haunting the woods and fields around Toronto in search of nests and eggs to photograph. George was what I might call a reformed öologist—an egg collector—who turned his attention to photographing rather than collecting birds’ eggs when that hobby became not only illegal [2] but scorned and prosecutable in the 1960s. George was a professional veterinarian who was well aware that prosecution for egg-collecting would destroy his career.

When I first met George in the mid 1960s he still had his boyhood egg collection, as it was still legal to possess one then, even though you could not legally collect wild birds’ eggs. With the advent of Kodachrome II and decent colour photography George made it his goal—his life list, if you will—to photograph the nest and eggs of every North American breeding bird, and to building the Ontario Nest Record Scheme into one of the largest and most accurate records of nesting birds ever compiled. George called himself a nidiologist, a term I never hear anymore.

Back in the day—as in the late 1800s—hundreds, no thousands, of men and boys (rarely women) would spend their spare time in summers hunting for birds’s nests and collecting eggs, for fun, for profit, or for science. Some wealthy men—like Walter Rothschild and Johnny Dupont—made huge collections that became the nucleus of many of the large collections in museums today.

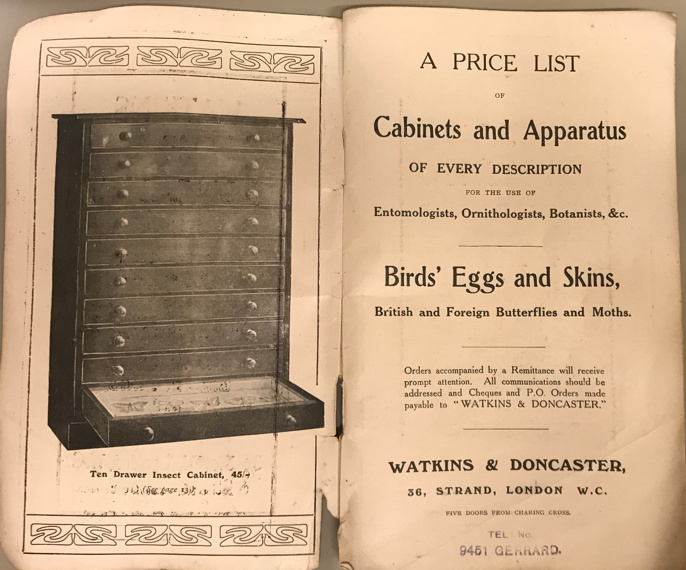

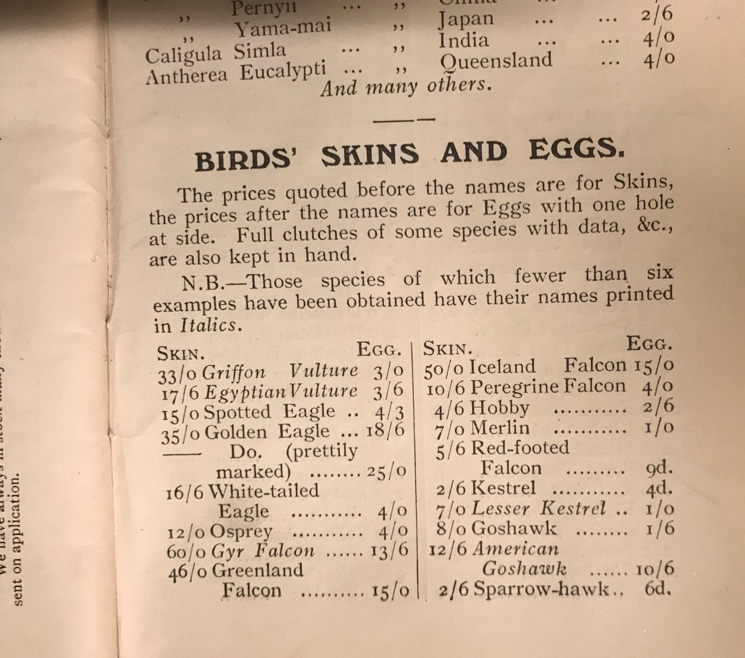

And there was money to be made because often the wealthiest of collectors did not go into the field at all, but amassed their collections through barter and purchase. For some men, egg collecting was an important source of seasonal income, and thousands of eggs were bought and sold both in personal transactions and by dealers. One dealer, Watkins & Doncaster [3], in 1900, would sell you a Golden Eagle egg for 18/6 ($119.64 in today’s $US), or a Honey Buzzard egg for 7/0 ($45.36 today) [4]. Even the egg of a common British garden bird like the Blackbird would cost 7d (54 cents). As you might expect, price was driven by supply and demand, and demand was driven by the rarity of the bird and the egg pattern [5]. Even given the vendor’s markup, a man could make a decent wage collecting birds’ eggs during the summer.

And there was money to be made because often the wealthiest of collectors did not go into the field at all, but amassed their collections through barter and purchase. For some men, egg collecting was an important source of seasonal income, and thousands of eggs were bought and sold both in personal transactions and by dealers. One dealer, Watkins & Doncaster [3], in 1900, would sell you a Golden Eagle egg for 18/6 ($119.64 in today’s $US), or a Honey Buzzard egg for 7/0 ($45.36 today) [4]. Even the egg of a common British garden bird like the Blackbird would cost 7d (54 cents). As you might expect, price was driven by supply and demand, and demand was driven by the rarity of the bird and the egg pattern [5]. Even given the vendor’s markup, a man could make a decent wage collecting birds’ eggs during the summer.

I would never advocate a return to egg-collecting as a hobby or a vocation, but as I have mentioned before, the great—and scientifically important and useful—egg collections of the world have stagnated, having added precious few specimens for decades. Many of them are also poorly curated, protected, and catalogued, though recently I have seen some renewed interest on the part of museum curators.

As a working scientist, I can’t even watch birds or record their songs without approval from our Animal Care Committee, let alone find nests and photograph eggs. The general public, of course, is not so restricted, but there is little amateur interest in nests and eggs anymore. Done carefully, and maybe under permit, there would seem to be some value in a renewed interest in nidiology, but that might be too fraught with conservation issues to be very attractive to most people.

There are, of course, always books to read in the summer, and this year there is a superb crop of books for those interested in reading about birds. I have the following pile of books relevant to the history of ornithology on my desk, and will write reviews of most of them in the coming weeks. For now, just a brief description of each book is about.

Birkhead TR (2018) The Wonderful Mr Willughby: The first true ornithologist. London: Bloomsbury. [Francis Willughy and John Ray tried to revolutionize natural history in the 17th century. Their classic Ornithologia Tres Libris was really the first encyclopedia of ornithology, with detailed description of all the species known to them. Willughby died when he was only 36, so Ray wrote up all of their findings in classic works on ornithology, fishes and insects. Ray got most of the glory….until now]

Birkhead TR (2018) The Wonderful Mr Willughby: The first true ornithologist. London: Bloomsbury. [Francis Willughy and John Ray tried to revolutionize natural history in the 17th century. Their classic Ornithologia Tres Libris was really the first encyclopedia of ornithology, with detailed description of all the species known to them. Willughby died when he was only 36, so Ray wrote up all of their findings in classic works on ornithology, fishes and insects. Ray got most of the glory….until now]- Brunner B (2017) Birdmania: A remarkable passion for birds. Vancouver: Greystone Books. [A somewhat eclectic compilation of interesting stories about some of the characters that populate the history of ornithology.]

- Johnson KW (2018) The Feather Thief: Beauty, obsession, and the natural history heist of the century. London: Hutchinson. [The intriguing story of Edwin List who stole valuable bird specimens from the British Museum to get feathers to make expensive flies for fishing]

MacGhie HA (2017) Henry Dresser and Victorian Ornithology: Birds, books and business. Manchester: Manchester University Press [While the focus here is on the life of Henry Dresser, from Manchester, UK, this book is a superb window on the state of ornithology in the late 1800s]

MacGhie HA (2017) Henry Dresser and Victorian Ornithology: Birds, books and business. Manchester: Manchester University Press [While the focus here is on the life of Henry Dresser, from Manchester, UK, this book is a superb window on the state of ornithology in the late 1800s]- Olina GP (2018) Pasta for Nightingales: A 17th century handbook of bird-care and Folklore. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press [this is the first English translation, by Kate Clayton, of one of the classics of early ornithology written ins 1622. Replete with contemporary watercolours from Olina’s day.]

Zalasiewicz J, Williams M (2018) Skeletons: The frame of life. Oxford: Oxford University Press [Despite the cover photo, there is not much in this book about birds, but what there is is fascinating, and nicely places birds in the evolution of skeletons. I have already reviewed this book for Times Higher Education in the 14-20 June 2018 issue]

Zalasiewicz J, Williams M (2018) Skeletons: The frame of life. Oxford: Oxford University Press [Despite the cover photo, there is not much in this book about birds, but what there is is fascinating, and nicely places birds in the evolution of skeletons. I have already reviewed this book for Times Higher Education in the 14-20 June 2018 issue]

Footnotes

- George Peck: was mentioned in my previous posts here, here and here

- egg-collecting illegal: In the UK the Protection of Birds Act of 1954 made the colection of birds’ eggs illegal. In tNorth America, that protection began with the Migratory Birds Treaty Act of 1918, but egg collecting continued largely unprosecuted until the UK act of the 1950s. The history of these laws and their enforcement is definitely complex and will be the subject of a later post

- Watkins & Doncaster: established in 1874, is still in business, though they no longer sell birds’ eggs. They moved from their location on The Strand in London in 1956, and are now in Hertfordshire (and, of course, on the internet)

- egg prices: are listed as shillings/pence in their catalog. I used this site to convert those amounts to today’s currency.

- rarity of egg pattern: see here for my previous post on an interesting and rare egg pattern

Hi Bob

Brunner´s book has been translated from German, but to tell you the truth not realy worth while to be read. A compilation of quite well known facts without going into depth, some myth and nothing new and no comparison to the other ones on your list

best regards

Josef