I did my PhD field work in Nayarit, Mexico, mainly in the coastal town of San Blas. On our first long drive there from Montreal, my fellow PhD student—Neil Brown—and I attempted to learn some basic Spanish, using a small Berlitz guide. Neil dropped me off just outside town, then headed off to his own study area near Tepic, in the mountains. I soon found a place to stay and went to the local tienda to get food. Wanting to try out my new Spanish, I asked the young male owner “¿Tiene huevos?” to which he gave a sheepish smirk and pointed to a basket on the counter full of fresh eggs. After a couple of weeks of this, he said he’d help me learn some Spanish, beginning with the proper way to ask for eggs (¿Hay huevos?)—I was really asking him if he had any testicles. My Spanish has not much improved in the intervening 45 years but my scientific interest in both eggs and testes has vastly expanded.

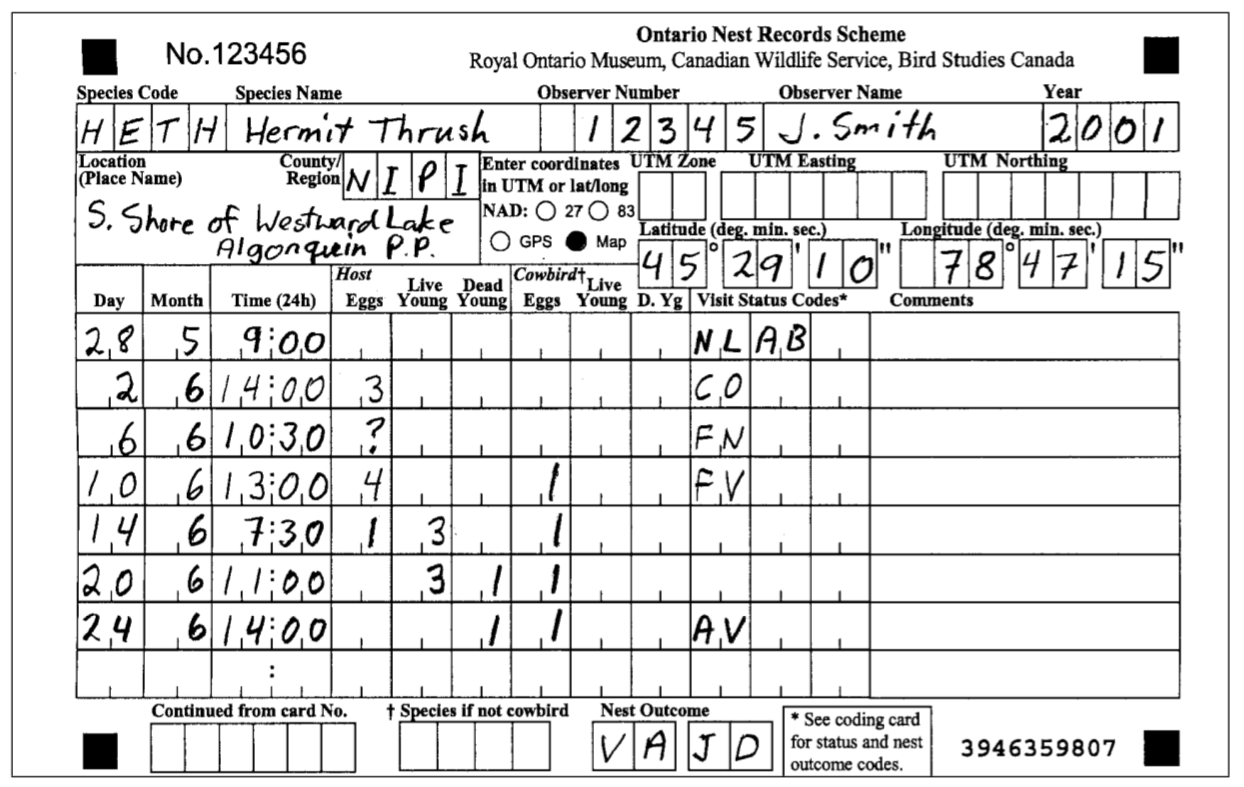

Like generations of teenage boys before me, I collected birds’ eggs. Unlike most of them, however, my collection was almost entirely photographic. In 1965, while still in high school, I had the good fortune to meet George Peck, a veterinarian who had just volunteered at the Royal Ontario Museum to coordinate the Ontario Nest Records Scheme (ONRS). This ‘scheme’ began in 1956 as a collection of file cards, one per nest, summarizing details about the location, clutch or brood size, and, sometimes, the history and fate of a nest found in Ontario. The ONRS was modeled after a similar scheme run by the British Trust for Ornithology.

George Peck was then an avid birder and (former) egg collector who had made it his lifelong hobby to photograph the nest and eggs of every North American bird [1]. For several years we spent many a weekend searching for nests throughout southern Ontario, photographing their contents and, often, setting up blinds to watch and photograph the parents as well. By the mid-1960s egg-collecting was illegal in Ontario [2] so we only took (and preserved) eggs from abandoned nests. George was always extremely careful around birds’ nests to minimize the risk of disturbing the parents and he taught me a lot about being a careful observer and note-taker.

Today the ONRS contains more than 120,000 nest records and provides a superb historical record of the distribution and other details (that George liked to call ‘nidiology’) of breeding birds in Ontario. Peck and James used these records to compile the first distributional and nidiological survey of breeding birds in Ontario, an early and quite successful product of citizen science.

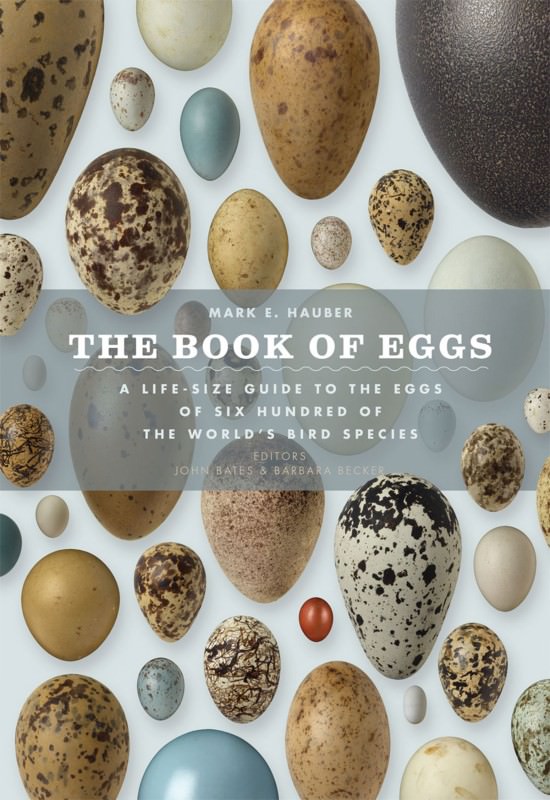

I am writing this post on Easter Egg Weekend, at a time when we are seeing something of a renaissance in the scientific study of birds’ eggs. Just last Saturday (31 March), BBC TWO aired a special on The Wonder of Eggs, hosted (of course) by David Attenborough [3]. And last year, birds’ eggs were on the cover of Science, with a comprehensive paper on the evolution egg shape by Cassie Stoddard (Princeton Univ) and her colleagues. Recent books by Tim Birkhead (Univ Sheffield) in 2016 and Mark Hauber (Univ Illinois) in 2014 have respectively highlighted both the exquisite biology and the amazing diversity of bird’s eggs.

As a budding oölogist [4], I devoured the Romanoff’s 1949 classic The Avian Egg, but by the time I started graduate school in the 1970s research on birds’ eggs had largely fallen by the wayside. I suspect that the scientific study of wild birds’ eggs was a victim of the demonization of egg-collecting by conservation groups and the very strict laws that eventually became established in Europe and North America. In some places, these laws even make the private curation of an egg collection illegal and have lead to the—in my opinion senseless—destruction of countless egg collections.

Freud would undoubtedly have had a field day speculating on the association between egg-collecting and adolescent males. But I suspect he would have been wrong, as he was in much of what he wrote. While I was doing my PhD field work in San Blas, I met a local Huichol artist named Fermin Gonzalez de la Cruz who sold me a couple of his excellent yarn paintings. The details of one are shown to the right and were featured on the cover of National Geographic several years ago.

Freud would undoubtedly have had a field day speculating on the association between egg-collecting and adolescent males. But I suspect he would have been wrong, as he was in much of what he wrote. While I was doing my PhD field work in San Blas, I met a local Huichol artist named Fermin Gonzalez de la Cruz who sold me a couple of his excellent yarn paintings. The details of one are shown to the right and were featured on the cover of National Geographic several years ago.

Many of the Huichol men that I encountered wore sombreros adorned around the rim with trinkets, and one of those men’s trinkets were mummified hummingbirds. I was studying hummingbirds, so this really intrigued me. When I asked him about it, he told me that hummingbirds were the traditional sombrero ornaments in his culture [5]. They were hard get, he said, so they became a sign that the bearer was a good hunter. As a budding behavioural ecologist, I interpreted that as a signal of status either to other males, or to potential mates.

Many of the Huichol men that I encountered wore sombreros adorned around the rim with trinkets, and one of those men’s trinkets were mummified hummingbirds. I was studying hummingbirds, so this really intrigued me. When I asked him about it, he told me that hummingbirds were the traditional sombrero ornaments in his culture [5]. They were hard get, he said, so they became a sign that the bearer was a good hunter. As a budding behavioural ecologist, I interpreted that as a signal of status either to other males, or to potential mates.

Birds eggs are one of several jewels of the bird world, not only beautiful but also delicate, hard to find, and (potentially) wearable. I do not know if there are any cultures that used bird eggs as ornaments but I do wonder if the European and North American obsession with egg collecting in the late 1800s was as much a signal of status as a desire to learn more about avian biology.

Regardless of the underlying psychology, the great egg collections now housed and curated in the museums of the world are a treasure trove of scientific and historical material—a subject that we will explore often on this site. Many avid (and, of course, male) collectors donated their large collections to—or indeed established—museums.

In Britain, the magnificent collection of more than a million eggs at the British Museum (Natural History), got a head start from an egg collector when Walter Rothschild donated his extensive collection (and his estate at Tring) in the 1930s. Similarly the superb egg collections at the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology in Camarillo, California (by Ed Harrison) and the Delaware Museum of Natural History (by John du Pont) were both established by avid, even obsessive, egg collectors. In Britain, once the Protection of Birds Act [6] was passed in 1954, many private egg collections were destroyed by fearful owners, or zealous enforcers of the law [7].

It is often said that we should study history to provide lessons for today. From the history of oölogy, we should have learned that egg collections: (i) are a valuable scientific resource, (ii) can help to solve some conservation problems [8], and (iii) are relatively easy to preserve. There is also no concrete evidence that the collecting of even thousands of eggs had any real impact on all but a very few very rare bird species. While I would never advocate the collecting of eggs as a hobby, as it once was, I feel that some of the current restrictions on scientific egg collecting are misguided.

When Paul Sweet of the American Museum of Natural History was asked recently how many eggs were in their collection [9], he answered, apparently without hesitation, 17,921. He knew that number precisely, he said, because it had not changed in years. That’s really a shame as there is much useful information being lost when museums do not maintain an active egg-collecting program, one that minimizes any possible damage to bird populations while maximizing the usefulness of the specimens through careful preservation, data collection and curation.

SOURCES

-

Birkhead T (2016) The Most Perfect Thing: Inside (and Outside) a Bird’s Egg. London: Bloomsbury.

-

Hauber ME (2014) The Book of Eggs: A Guide to the Eggs of Six Hundred of the World’s Bird Species. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hauber ME (2014) The Book of Eggs: A Guide to the Eggs of Six Hundred of the World’s Bird Species. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. -

Peck GK, James RD (1987) Breeding birds of Ontario: nidiology and distribution (2). Toronto: Alger Press.

- Ratcliffe DA (1967). Decrease in eggshell weight in certain birds of prey. Nature 215: 208-210.

- Romanoff AL, Romanoff AJ (1949) The Avian Egg. New York: John Wiley and Sons

- Stoddard MC, Yong EH, Akkaynak D, Sheard C, Tobias JA, Mahadevan L (2017) Avian egg shape: Form, function, and evolution. Science 356: 1249-1254.

Footnotes

- George Peck: managed the ONRS for the rest of the century, elevating it to probably the best such set of nest records in North America. He continued to photograph nests and eggs until his eyesight failed him, coming very close to his goal of photographing all North American species. His son, Mark, now works at the ROM and continues his father’s interest in eggs and photography.

- egg collecting illegal in Ontario: as far as I can tell, egg collecting actually became illegal across North America, at least for migratory birds, with the Migratory Birds Convention Act of 1918. Apparently, that part of the act was rarely, if ever enforced with respect to the hobby, until the 1050s at least

- Attenborough’s Wonder of Eggs: has not yet aired in North America but you might be able to watch all of it (if you are in the UK) or some short clips on the BBC TWO website, and you can read about it here

- oölogist: literally means ‘one who studies’ eggs, but the term has been applied only to birds’ eggs; during the late 1800s and early 1900s ‘oölogist’ meant ‘egg collector’ so the term is not used very often today, except by scientists

- hummingbirds on sombreros: Some recent sources suggest that this story is apocryphal (though my story is true); while the hummingbird was imbued with mythological powers by the Huicholes, they apparently adorned their sombreros with a wide variety of natural objects in prehistoric times but now, like satin bowerbirds, use readily available man-made objects as decorations

- Protection of Birds Act of 1954: you can read a little bit about it here; I suspect that the passing of this Act had some influence on egg-collecting in North America, as well, even though egg-collecting had already been ‘illegal’ here for 36 years.

- destroying egg collections: Freud would undoubtedly have had a field day speculating on the psychology of the egg crushers

- egg collections solving conservation issue: the measurement of the eggs of some species in collections was key in pinpointing the effects of DDT on declining Peregrine Falcon populations (see Ratcliffe 1967)

- number of eggs in AMNH collection: quoted in an article in The Atlantic

IMAGES: Huichol shaman from Wikipedia; all other photographs by the author

COMMENTS