The more I read about the history of ornithology, the more it strikes me how important serendipity—blind luck—has been to that history. Ernst Mayr’s career, for example, was a long series of fortunate events. No question that Mayr was brilliant, ambitious and creative, but the goddess of fortune was definitely smiling on him.

One hundred and twelve years ago today, San Francisco lay in ruins, decimated [1] by 4 days of fires that followed the earthquake that struck in the early morning on 18 April 1906. The earthquake itself was monstrous but it was the fires—fuelled by broken gas mains and the largely timber construction of much of the city—that wreaked the most havoc for four consecutive days following the initial quake. Charles Richter was only 6 years old in 1906—and thus had not yet invented his eponymous scale—but geologists figure that the Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake would have numbered 7.9 on that scale.

The California Academy of Sciences was destroyed by the quake and most of its specimen collections burned in those fires. Nonetheless, a particularly valuable portion of the herbarium [2] was rescued by the heroics of Alice Eastwood, the curator of botany. The museum director Leverett Loomis was able to rescue only two bird books and two bird specimens (both of the Guadalupe Storm Petrel [3]) but all of the other ornithological material was lost.

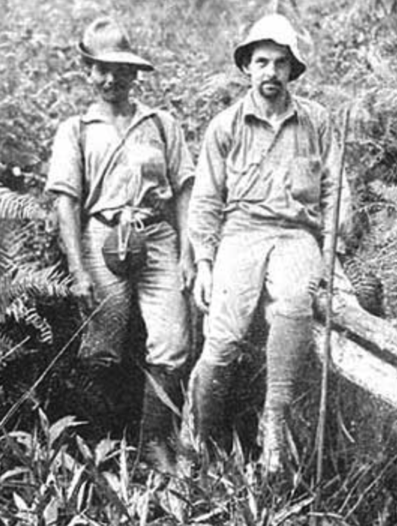

While the Cal Academy’s bird collection was lost, there was a serendipitous silver lining in that cloud of smoke. In 1904, Loomis had commissioned Rollo Beck to lead a 17-month-long collecting expedition to the Galápagos. Beck was a superb collector who lived in California making extensive collections of birds along the west coast of North America for museums and private collectors like Sir Walter

Rothschild, who figures prominently in Ernst Mayr’s story of success. Loomis, however, had a ton of trouble trying to find a suitable ship to either buy or lease for that expedition. So the departure date had to keep being advanced from October 1904 until the end of June 1905 when they finally were able to leave San Francisco on the rebuilt schooner Academy. If the expedition had left in 1904, as originally planned, it would have returned in March 1906 just in time to be burned by the fires of April.

Thus, in April 1906, when the Cal Academy collections burned, Beck was still in the Galápagos. He returned in November 1906 bringing with him more than 78,000 specimens—including 8688 birds (3200 of which were Galapagos Finches [4]) and 2000 birds’ eggs —that would form the nucleus of the collections in the rebuilt museum [5]. The Cal Academy restored the museum and reopened in 1916, then rebuilt the whole structure with improved earthquake and fire protection in 2008. It is a magnificent museum, aquarium and small zoo today and well worth a visit next time you are in San Francisco. It also still holds the largest collection of Darwin’s Finches in the world. Those specimens formed the basis for much of the work that Robert Bowman and David Lack did on the anatomical adaptations of those birds [6].

Beck was later hired by the American Museum of Natural History to head the Whitney South Sea Expedition to the south Pacific islands to collect birds and anthropological material. Beck set out with his crew in 1923 but in 1929 he got very sick and had to go home. That left the expedition without an ornithologist. Sir Walter Rothschild knew

about the 24-year-old Ernst Mayr then working as an assistant to the great German ornithologist Erwin Stresemann in Berlin. Rothschild had promised Mayr a collecting trip to the tropics on completion of his PhD in 1922 but no opportunities had presented themselves until 1928 when he was able to send Mayr to New Guinea. Thus Mayr was in the right place at the right time when the Whitney expedition needed a new ornithologist so Rothschild asked him if he could take over to complete the work that Beck had started. After returning to Europe in 1930, Mayr moved to New York to work on the specimens collected on the Whitney expedition and established his early career with those publications. And the rest, from those very lucky beginnings, is history.

The take home lesson from Serendipity 101 is that ‘shit happens’, but good things happen too and there is really nothing we can do about many of those devastating events like earthquakes. What we can do, as Ernst Mayr’s life so amply demonstrates, is to recognize and be prepared to take advantage of the good things, and to try not to be too discouraged when the goddess of fortune [7] takes a holiday.

SOURCES

- Bowman RI (1961) Morphological differentiation and adaptation in the Galapagos finches. University of California Publications in Zoology 58:1–302.

-

Godman FDC (1907) Monograph of the Petrels (order Tubinares). London: Witherby & Co.

- James MJ (2012) The Boat, the Bay, and the Museum: Significance of the 1905-1906 Galápagos expedition of the California Academy of Sciences. Pages 87-99 in Wolff M, Mark Gardener M (editors) The Role of Science for Conservation. London: Routledge

- Lack D (1945) The Galápagos finches (Geospizinae): A study in variation. Occasional Papers of the California Academy of Sciences 21:1–159.

- Lack D (1947) Darwin’s Finches. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lowe P (1936) The finches of the Galápagos in relation to their evolution. Ibis 1936:310–321.

Footnotes

1. Decimated: literally reduced to 1/10th of its former size as 90% of the homes were destroyed. See here for a summary of the effects of those fires

2. Valuable portion of the collection: these were type specimens that Eastwood had kept separate from the main collection. This was an unusual practice in those days but proved to be lucky as she was able to grab them in a few minutes. On arriving at the museum, she found that the marble staircase had collapsed so she climbed to the 6th floor herbarium on the iron railing. She then gathered up those type specimens with her friend Robert Porter. Eastwood then climbed back down the bannister to the ground floor to gather up the specimens that Porter lowered out the window, on a rope that they had put together from scraps. See here for more details.

3. Guadalupe Storm Petrel: although this bird was still considered to be abundant on its Guadalupe Island (Mexico) breeding grounds in 1906, it was being heavily preyed upon by cats that were introduced to the island in the late 1800s. The last two specimens were collected in 1911 and the last breeding was recorded in 1912. The species was never seen again (see here for more details). Loomis must have taken these two because they were the type specimens as he could not have guessed that the species was soon to be extinct. The painting by JG Keulmans is from Godman (1907)

4. Galápagos Finches: were not normally called Darwin’s Finches until Percy Lowe (1936) used that term

5. Galápagos expedition of 1905-06: see James (2012) for details

6. Lack and Bowman studies of Darwin’s Finches: see Lack (1945, 1947) and Bowman (1961)

7. Goddess of Fortune: Tyche to the Greeks, Fortuna to the Romans

IMAGES: all from Wikipedia, in the public domain