26 February 2018

Mr Charles Darwin

Westminster Abbey

UK

My Dear Charles

My apologies for not writing last Monday as I had suggested I might when I wrote to you on your birthday. We were still on the Santa Cruz II ‘steaming’ from Floreana to Baltra on Monday morning and there was no way yo get a message out. I thought of leaving a postcard for you in the barrel at Post Office Bay on Floreana but that might take months to get to you, or be stolen by a tourist.

We had a great visit to the Galápagos Islands, stopping on Baltra, Santa Cruz (Cerro Dragon and Puerto Ayora), Isabela (Punta Vincente Roca), Fernandina (Punta Espinoza), and Floreana (Punta Cormoran and Post Office Bay) to hike, snorkel and/or simply watch and photograph wildlife. I see from your Voyage of The Beagle that you, too, stopped on Charles Island (now called Floreana) and Albermarle (now Isabela), but you also went to Chatham Island (now San Cristobal) and James Island (now Santiago). Certainly, things have changed since you were in the islands in Sept-Oct 1835.

First, and maybe most strikingly, there are now a lot of people on the Galápagos Islands. There are now settlements on Santa Cruz, Baltra, San Cristobal, Floreana and Isabela, by far the largest being Puerto Ayora on Santa Cruz with maybe 25,000 inhabitants (though ‘officially’ 15,000). On top of that a staggering 225,000 people visited the islands in 2015, by boat or plane. The islands are now almost entirely a national park, so travel is restricted to 54 sites on land and 62 for diving in the surrounding ocean. Visitors are limited to about 4 hours per site and must be accompanied by a trained guide.

Fortunately, the places we visited (except Puerto Ayora and vicinity) seemed to be in a relatively pristine state with well-marked trails, no trash, and abundant wildlife close at hand. The birds and reptiles are still exceptionally tame and the waters clear and teeming with life.

The (your) finches were also common to abundant just about everywhere we went. They certainly have not been scared off by human developments as we saw them even inside the airport buildings on Baltra and throughout the town of Puerto Ayora. Even we seasoned ornithologists and birders found the species hard to distinguish on any given island so you are to be forgiven for not initially noticing the proliferation of finch species there. The downside of increased human traffic to the islands is that we saw a high incidence of foot pox in the finches on Baltra, and a parasitic nest fly (Philornis downsi) is now posing a serious threat to some finch populations [1]. The finches are so closely associated with humans in some places that there now signs posted to tell people not to feed the birds.

You will recall that John Gould identified 12 species of ‘Galápagos’ finches from your collections. There continues to be debate about how many finch species are actually on the islands, especially as we are now using new molecular tools to help distinguish evolutionarily stable populations that might be worth designating as distinct species. During the 20th century biologists often defined species as reproductively isolated populations (the ‘Biological Species Concept’) but that has proven to be difficult to test empirically and not always useful, in my opinion. At my count there are now at least a half dozen ways to define species and the debate continues in a lively (and I think very productive) fashion.

The Handbook of Birds of the World Online now lists 14 species of Geospiza, plus the Vegetarian Finch (Platyspiza crassirostris), the Grey Warbler-finch (Certhidea fusca), and the Green Warbler-finch (Certhidea olivacea) for a total of 17 species of Darwin’s Finches. I expect that DNA analysis will add to this total in the coming years.

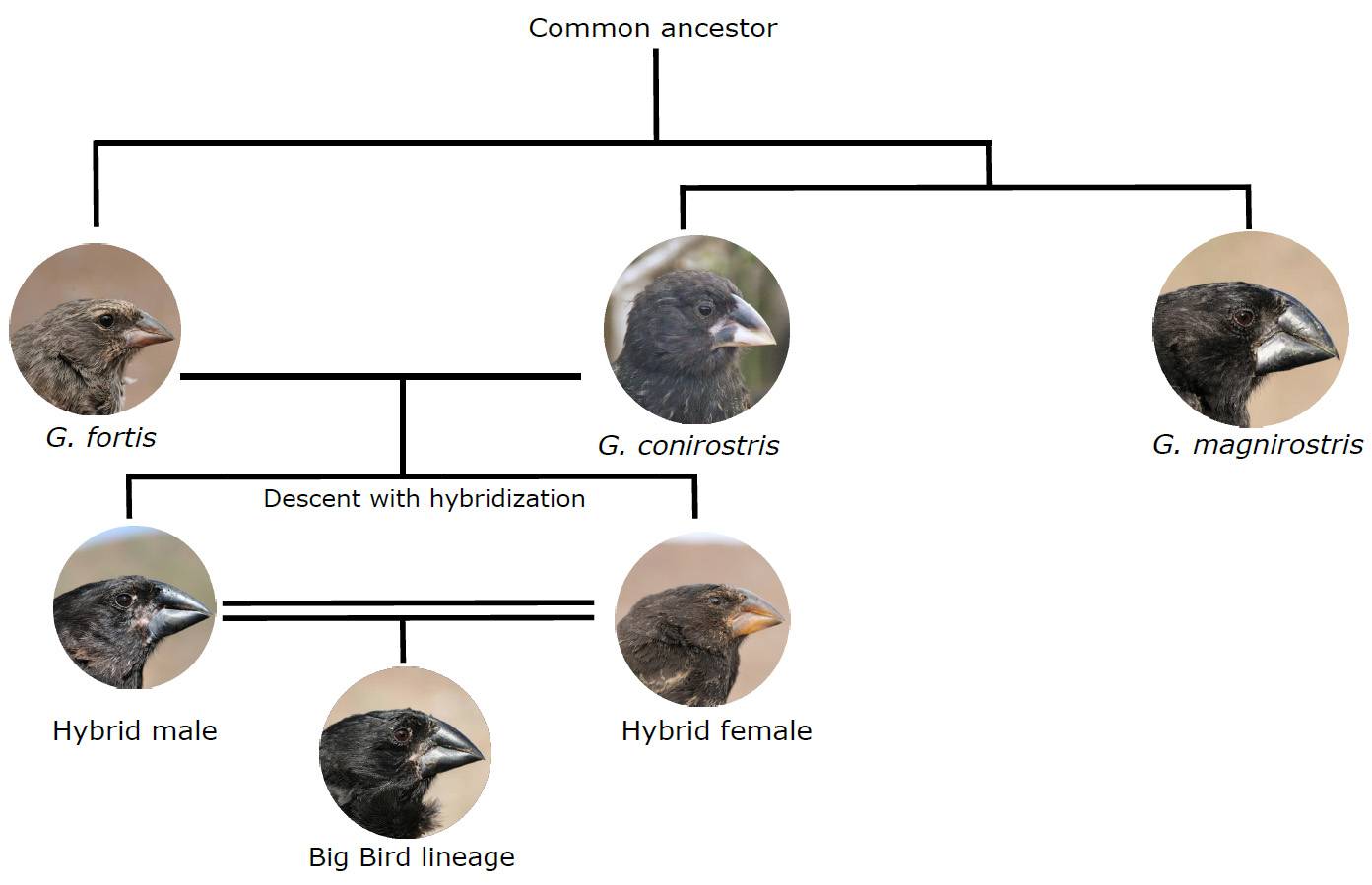

Peter and Rosemary Grant also discovered an instance of speciation through hybridization of an immigrant male Geospiza conirostris from Española Island with a female resident Geospiza fortis on Daphne Major in 1981 [2]. The descendants of this pairing (the Big Bird Lineage, see below) have only mated with each other over the last 37 years. These birds are reproductively isolated from the resident population of G. fortis by their distinctive song. Odds are that this tiny population of the hybrid species will go extinct, but the documentation of this event has given us an insight into a form of speciation that you may not have anticipated, though it is likely to be quite rare.

Sadly, some of the tortoises that you recognized as being distinct species are now extinct due to hunting by sailors, collecting by museums, predation by introduced rats and cats, and habitat destruction by goats. It is estimated, for example, that 200,000 tortoises were taken from the islands before 1900. The tortoise (Chelonoidis abingdoni) from Abingdon Island (now Pinta) went extinct only 6 years ago when the last male (“Lonesome George”) died in captivity at the (relatively young) age of just over 100 years. George was preserved as a taxidermic mount and is now on display at the Charles Darwin Research Station in Puerto Ayora. Also now extinct is C. nigra from Floreana, which you saw and collected, was extinct by 1846 having been hunted mercilessly by sailors and the penal colony on that island; and C. phantastica from Narborough Island (now Fernandina) which is known only from a single specimen collected by Rollo Beck for the California Academy of Sciences in 1906. All of the other tortoise species are considered to be endangered or at least vulnerable with populations <10,000 each and some only in the 100s. There is hope, however, in restoring some of them by captive breeding and the eradication of predators.

As you might expect, your name is intimately associated with the Galápagos with an island (formerly Culpepper Island) now named after you, as well as a research station and a hostel in Puerto Ayora, a tortoise (C. darwini), and, of course, those finches.

Yr obd srvt

Bob

SOURCES

- Darwin C (1840) The zoology of the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, under the command of Captain Fitzroy, R.N., during the years 1832 to 1836. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Grant BR, Grant PR (2008) Fission and fusion of Darwin’s finches populations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 363:2821–2829.

- Kleindorfer S, Dudaniec RY (2006) Increasing prevalence of avian poxvirus in Darwin’s finches and its effect on male pairing success. Journal of Avian Biology 37:69–76.

- Koop JAH, Kim PS, Knutie SA, Adler F, Clayton DH (2016) An introduced parasitic fly may lead to local extinction of Darwin’s finch populations. Journal of Applied Ecology 53: 511–518.

Footnotes

1. parasitic nest fly and foot pox: see Koop et al. 2016 on the fly and Kleindorfer and Dudaniek on the pox

2. speciation through hybridization: see Grant and Grant (2008)

IMAGES: Big Bird lineage from https://www.princeton.edu/news/2017/11/27/study-darwins-finches-reveals-new-species-can-develop-little-two-generations; Galapagos map from http://www.prairiefirenewspaper.com/2009/02/reflections-on-charles-darwin; Post Office Bay photo from Wikimedia Commons; all other photos by the author