CELEBRATING

THE HISTORY OF WOMEN IN ORNITHOLOGY

In one of my earliest memories—I must have been about 6 years old—it is summer and I am sitting in my grandfather’s garden as his seven hens and a rooster forage around me, almost within touch. I am watching them closely, giving each of them personalities, figuring out who is boss, who is good at finding worms and grubs, and who is mainly stealing from the others rather than scratching for food of its own.

I was not interested in birds then, but as long as I can remember I have loved watching animals close up. To that end, I kept all manner of snakes, frogs, salamanders, fishes and insects in my bedroom when I was a teenager, often much to the horror of my poor mother when they escaped, as they did with alarming regularity. My second paying job (Dream Job #2)—for two summers right after high school—was to raise and care for hundreds of ducks, geese, swans, hawks, owls, racoons and skunks at the Niska Waterfowl Research Station [1], near Guelph, Ontario. Every day I got to watch at close range dozens of domestic and exotic species from all over the world, and to raise their babies.

This week I highlight the lives of two woman ornithologists who kept and raised hundreds of bird species over a span of 40 years, and in so doing made immense—and virtually unknown and unsung— contributions to our knowledge of bird behaviour, growth and development during the first half of the twentieth century.

Magdalena Wiebe [2] was born in Berlin, Germany in 1883 and became interested in birds at a very early age. By the time she was 20, she was already a skilled taxidermist and aviculturist. After her marriage in 1904, she stayed at home where she kept and reared hundreds of birds over the next 28 years, gathering data on the breeding, behaviour and development of almost all of the species commonly found in Europe.

Katharina Berger was born in 1897 in Breslau, Germany, and also developed an abiding interest in animals at an early age. At university she studied both botany and zoology and did her PhD with Otto Koehler, one of the pioneers of ethology. Along with Konrad Lorenz, Koehler founded the journal Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. Katharina, like Magdalena, was an expert bird keeper. She published several key papers on pigeon orientation and behaviour. In 1945 she was appointed director of the Berlin Zoo, a position she held until her retirement in 1957.

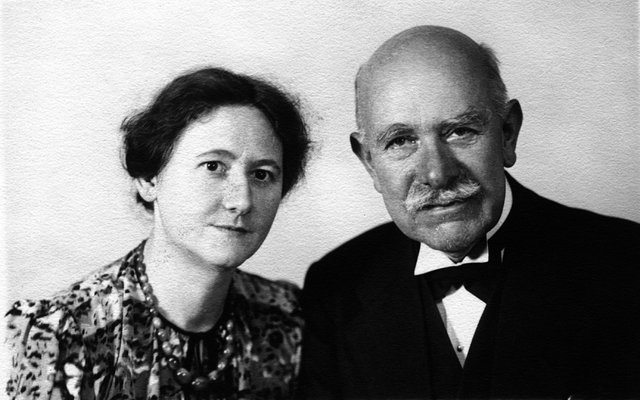

What Magdalena and Katharina had in common was that they were both married to Oskar Heinroth, though not, of course, at the same time. Heinroth also became interested in animals when he was very young. Though trained as a medic, Oskar took a position at the Zoological Garden in Berlin in 1904 when he was in his early 30s, and spent the rest of his life studying birds, with Magdalena, then Katharina, both responsible for looking after the birds they studied, and devoting their lives with Oskar to studying their birds at close range.

Magdalena learned taxidermy from Oskar at the Natural History Museum, before they were married. At their engagement, Oskar gave Magdalena a ‘pet’ Blackcap in lieu of a ring. That pet was a portent of things to come as Magdalena spent the next 28 years raising birds in their apartment. During that period Oskar was assistant director then director at the Berlin Zoo, and studied waterfowl behaviour in his spare time.

Magdalena clearly did not like the idea of sitting idly at home so began raising small birds to learn more about their behaviour and development. She bought some of them at local bird markets but often went afield to collect eggs to incubate and raise at home. Eventually they devoted an entire room in their apartment to the birds, though Oskar was initially a little skeptical about the value of Magdalena’s hobby.

Magdalena was a wizard at bird husbandry and fearless attempted to raise many species known to be tough to keep, let alone rear, in captivity: Goldcrests, Dippers and Tree Creepers, for example. Soon her goal was to try to raise every single bird species native to Germany no matter how big, small or difficult. Over that 28-year period she raised about 1000 individuals of 236 species, many of which were exceptionally tame and remained in the apartment as adults. This must have strained their domestic relationship and their neighbours as the birds were often noisy and undoubtedly smelly. And how did they keep the raptors from eating the smaller birds?

After 9 years, the Heinroths moved to a more more spacious apartment in the Aquarium building where they could devote several rooms to their birds and have a somewhat less impact on their personal lives and the neighbourhood. The Aquarium was built in 1913 and was (and is) part of the Berlin Zoological Garden where Oskar was Director. This must have been a much more convenient living/working situation for the couple. With both facilities and subjects close at hand, the Heinroths were able to greatly expand the scope of their research (and, presumably, the size of the birds that they could house!).

Both the birds and the research took their toll on the couple, as they functioned on precious little sleep during the busy spring and summer breeding season. Oskar was also allergic to either feathers or the mealworms that they raised to feed the birds. He only recovered from his asthma when he stopped having birds in the house when this project ended rather abruptly in 1932.

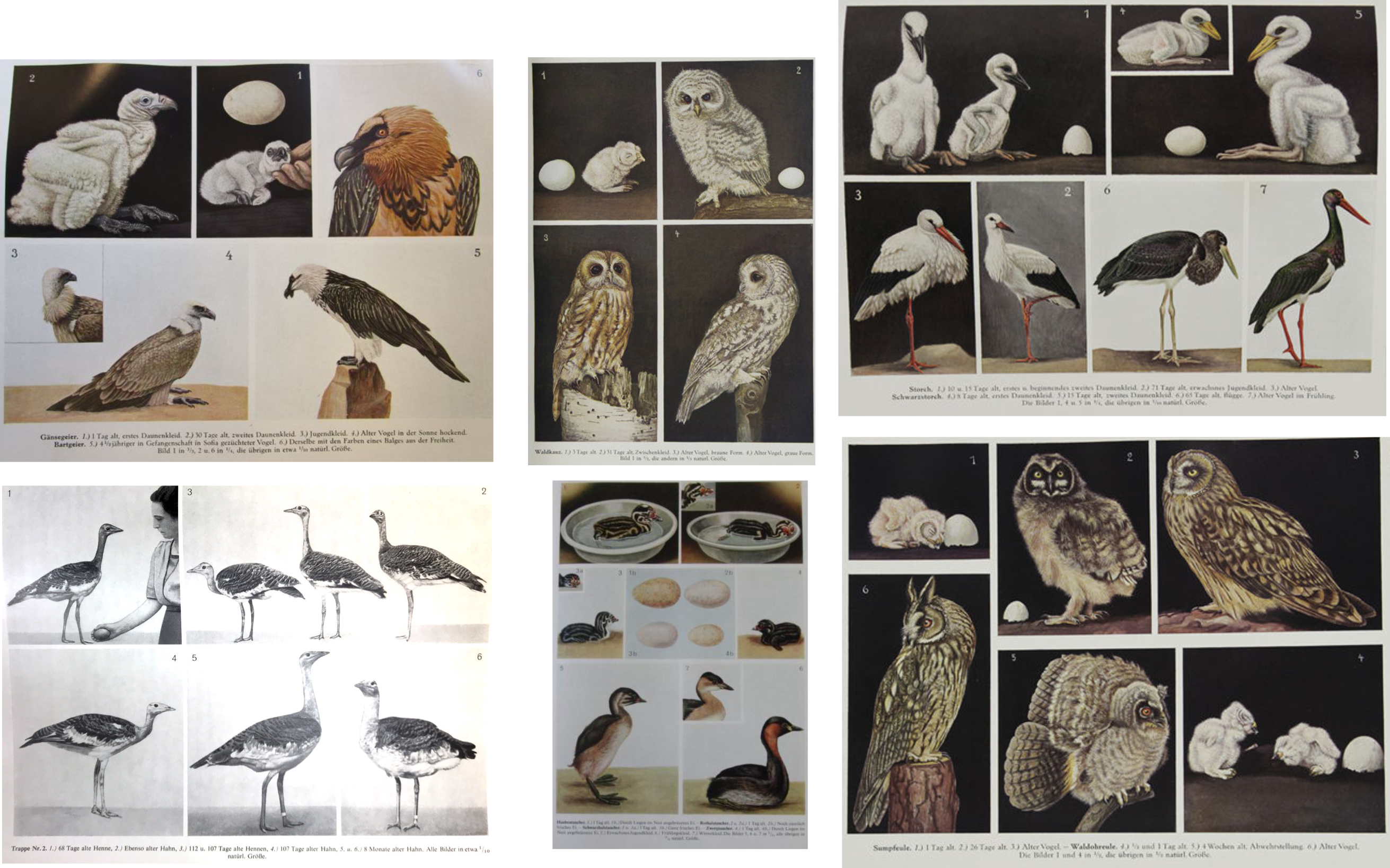

In addition to developing methods for the husbandry of a wide variety of species, the Heinroths measured growth, studied the development of locomotion, behaviour, and moult. They recorded everything in notebooks supplemented with more than 15,000 photographs of life stages and behaviours. For many of the birds they also drew or photographed the gapes of nestlings, realizing that this was an important signal to parents. It certainly did not escape Magdalena’s notice that they were on to something transformative in the study of behaviour: ‘‘Yes, it is often almost impossible to properly investigate the finer aspects of the habits of small birds in the wild …. If we … wish to get exact answers, the best thing is to keep the birds (in captivity), to do everything for them and observe them continuously’’ [3]

After 20 years of gathering this information and photographing their birds, the Heinroths began to put it all together in what was eventually a four-volume treatise published between 1924 and 1933. For each species they summarized all of their observations and measurements, and provided a series of 4040 photographs documenting various stages of development from egg to adult (see example pages below). In several of the photos, either Oskar or, more often, Magdalena, are visible, either for scale or simply to acknowledge the tameness of the birds. The book and their work in general is an important milestone in the history of ornithology, ethology and behavioural ecology. While their book was praised at the time, and is still monumentally useful, it and the Heinroths rather faded into obscurity [4].

After 28 consecutive years staying at home to rear birds, Magdalena took a holiday. The fourth volume of their book was now at the publisher, and Magdalena had suffered a couple of serious bouts of illness and really needed a break. After only two weeks away she suffered an intestinal blockage and died.

A year after Magdalena died and their project ended, Oskar married Katharina Berger. Kaethe had previously been married to Gustav Adolf Rösch, who was an assistant to Karl von Frisch [5] in Munich. When that union dissolved, she eventually moved to Berlin where she met and fell in love with Oskar. Like Magdalena, Kaethe also kept and studied birds, though presumably not in their apartment as the birds were pigeons and the subject was homing and orientation. With Oskar she published several influential papers on the subject. When Oskar died in 1945, Katharina was appointed scientific director at the zoo and initially spent her time restoring the zoo from the ravages of WWII. Long after Oscar died, Katharina wrote a book about his life and their lives together [6].

While Katharina’s life with Oskar was productive and undoubtedly rewarding, she outlived him by 43 years during which time she published many popular articles, an autobiography of her own life and a book about birds. That book, with Joachim Stenbacher, was illustrated by Ludwig Binder, and was published as the fifth in a series of looseleaf, boxed fascicles on a variety of European birds. This publishing methods is reminiscent of the subscription volumes of the 1800s, and the original printed species accounts in the Birds of North America series published by the American Ornithologists Union and the Academy of Natural Sciences (Philadelphia) in the 1990s [7].

SOURCES

- Heinroth K (1971) Oskar Heinroth––Vater der Verhaltensforschung. Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft

- Heinroth K (1979) Mit Faltern begann’s, Mein Leben mit Tieren in Breslau, München und Berlin. München: Kindler.

- Heinroth K, Stenbacher J (1962) Mitteleuropäische Vögel. Hamburg: Kronen-Verlag

- Heinroth M (1911) Zimmerbeobachtungen an seltener gehaltenen europa¨ischen Vo¨geln. Berichte V. Internat Ornithol Kongr Berlin 1910:703–764

- Heinroth O, Heinroth K (1941) Das Heimfindevermögen der Brieftauben. Journal für Ornithology 69:213–256

- Heinroth O, Heinroth M (1924–1933) Die Vögel Mitteleuropas—in allen Lebens- und Entwicklungsstufen photographisch aufgenommen und in ihrem Seelenleben bei der Aufzucht vom Ei an beobachtet. Band I–IV. Berlin: Hugo BehrmühlerVerlag

- Podos J (1994) Early perspectives on the evolution of behavior: Charles Otis Whitman and Oskar Heinroth. Ethology ecology & evolution 6:467–480.

- Rühl P (1932) Erinnerungen an Magdalena Heinroth. Journal für Ornithology 80: 542–551

- Schulze-Hagen K, Birkhead TR (2015) The ethology and life history of birds: the forgotten contributions of Oskar, Magdalena and Katharina Heinroth. Journal of ornithology 156:9–18.

Footnotes

- Niska Waterfowl Research Station: was the research wing of Kortright Waterfowl Park established by the Ontario Waterfowl Research Foundation in the 1960s. The research station collected, raised and looked after the waterfowl for the public park, as well as conducting research on the resident waterfowl. The Park was open to the public for about 40 years.

- Magdalena Wiebe: I exercised some artistic licence in calling her Magda in the title of this essay. Magda is the diminutive form of Magdalena in Polish, at least. Katharina, on the other hand, is referred to as Kaethe in various sources.

- quotation about birds in captivity: from Heinroth 1911, translated in Schulze-Hagen and Birkhead 2015 page 12

- faded into obscurity: as Schulze-Hagen and Birkhead (2015) point out, both political events and the changing focus of ornithology were probably responsible. In particular, it seems likely that publication of the work in German limited its potential audience among researchers in the English-speaking world who were leading the transformation of evolutionary and behavioural biology

- Karl von Frisch: one of the founders of ethology, he shared the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Konrad Lorenz and Niko Tinbergen

- Katharina’s book about Oskar: see Heinroth (1971), published 26 years after Oskar died

- Birds of North America: is now online here, and continues to be the most important source of information about all the birds of North America.

IMAGES: Kortright Park sign from article in Guelph Mercury here; Magdalena from Rühl 1932; Aquarium from Wikipedia; photo montages from Die Vogel Mitteleuropas scanned by the author; Katharina and Oskar from Wikipedia; Hooded Crow scanned by the author.

Oh, love this post. Here in Berlin I have been wondering about who the birders are in the area. I pass the Aquarium regularly. Who knew its avian history? I wonder if they knew my grandparents who lived here at the same time. I wonder if I can get my hands on any of these books. Hooded crows, shown in the post are an iconic bird of this area, though I have to say I love the timid hawfinches and bullfinches and the tiny but aggressive robins and tits.

Wow! Thank you for this knowledge-enriching piece. I love it!

The Catalyst