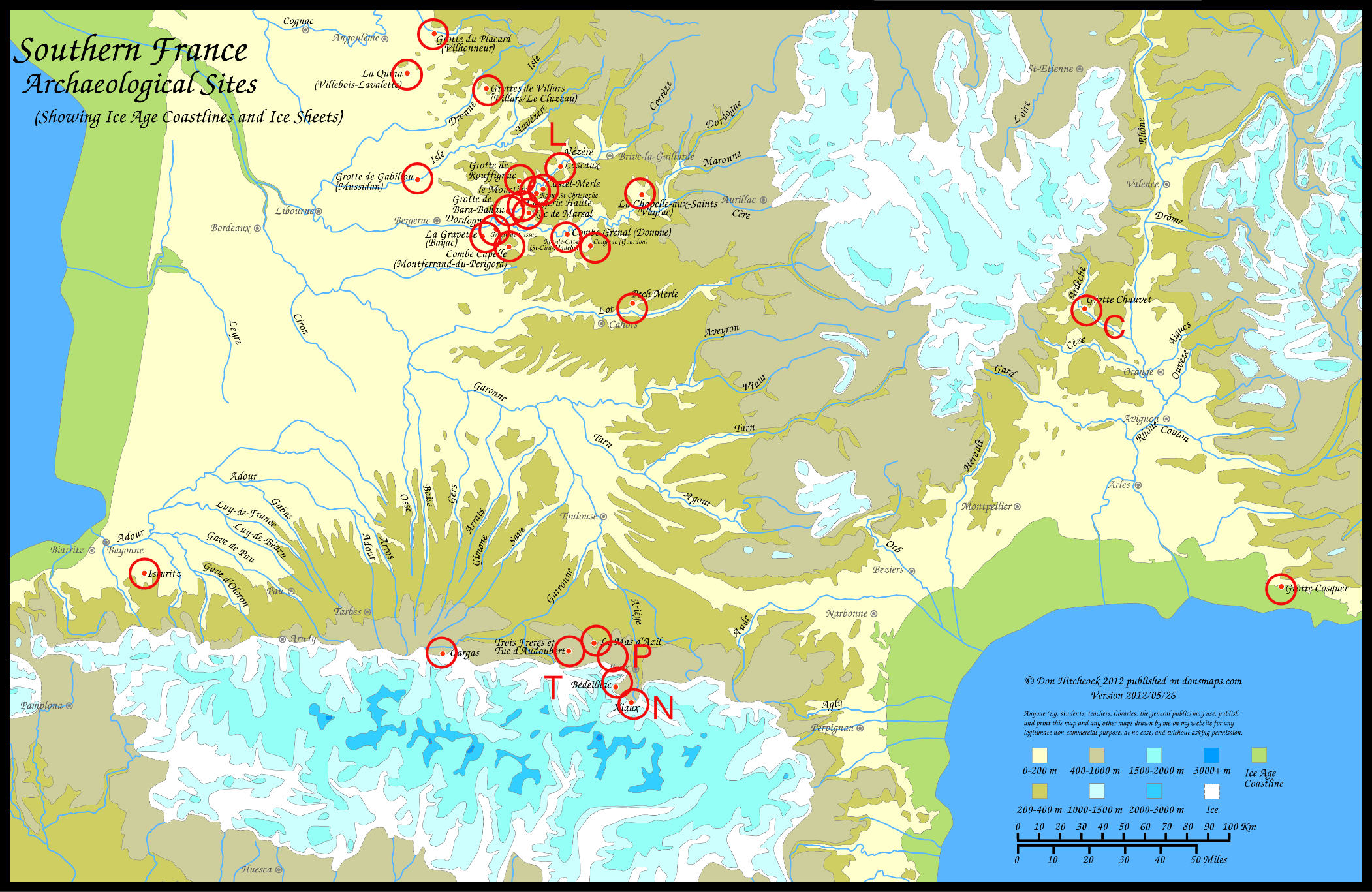

At the AOU (now AOS) meeting in Jacksonville, Florida, in 2011, Peter Stettenheim [1] gave a talk on ‘Cultural Images of Birds: A neglected source of information’. He suggested that the many images of birds in prehistoric cave paintings, hieroglyphics, carvings, rock art, and mosaics might yield useful ornithological information about former ranges and the process of domestication. I was not entirely convinced by his examples but my attention was piqued when he showed what looked like two owls scratched into the wall of the Cave of the Trois-Frères in Ariège départment in the south of France. Like the more famous caves at Lascaux and Chauvet, Trois-Frères had many images of animals and symbols painted and etched on its walls 15,000 to 35,000 years ago in the Upper Paleolithic period of human culture in western Europe.

Just before that conference, I had been in Ariège, near the Spanish border, doing research for three months out of the CNRS research station in Moulis, about 70 km SSW of Toulouse. During that field trip, I had visited the fabulous Grottes de Niaux, about 25 km due south of Foix, where I went on a tour of the magical paintings of aurochs, bison horses, deer and an even an ibex that adorned the walls deep into that cave. It seemed almost unbelievable that paleolithic peoples would have gone more than a kilometre into a cave to makes those paintings, even if they were done for shamanic rituals as is now supposed.

I did not see any paintings of birds in the cave at Niaux, and a quick search on the internet after I heard Stettenheim’s talk did not reveal any birds on the walls of the cave at Lascaux and only one—a very nice owl— at Chauvet [2]. I asked my colleague Alexis Chaine, a CNRS researcher at Moulis, whether he knew of any birds in cave paintings and he in turn asked the former director of the research station, Alain Mangin, who was a cave biology expert. Alain was reasonably certain that there was an owl in a cave on private property about 50 km east of Moulis so we asked him if we could get permission to explore that cave. A year later that permission was granted so Alain, Alexis and I, led by two friends of the property owner, visited that private cave—called Le Portel—in June 2012.

To get to the cave entrance, we walked about 500 m through the forest to what looked like nothing more than a small hole beside a big rock. Inside the hole, a locked grate kept out intruders. We unlocked the grate and down we went, squeezing ourselves through the narrow entrance. I am somewhat claustrophobic so the descent into a small hole in the ground to crawl, slither and walk underground for a few hours in a dark place under thousands of tonnes of rock is not much fun for me. But, on the other hand, I have never been one to pass up on what seemed to be a once-in-a-lifetime adventure. So in I went with headlamp, waterproof gear, and an iPhone that I knew would be no use underground except to take some pictures.

Within a half hour, we came across the first paintings of the usual bison, horses, and even what looked like a human. Then all of a sudden there it was, the owl, distinctive in both overall shape and its v-shaped bill. We saw maybe 50 paleolithic paintings in our three hours underground but only the one bird. There have also been birds found in more recent cave paintings in Australia, but they are outnumbered by the mammals by at least 100 (or maybe even 1000) to 1 in cave art worldwide

When I told Stettenheim about this owl, he responded that “The owl image that you saw at Le Portel is new to me and very interesting. That cave is well known to paleo-archaeologists, but they seem to have noticed only the large mammals, never the bird. The occurrence of owls both here at and at Trois Frères indicates that the bird was important to the people who drew it.”

Assuming that the animals shown in cave art were important to the people who painted them, I think we can conclude, from their rarity in the caves, that birds were actually not very important to paleolithic peoples, at least in Europe. For most prehistoric peoples, large mammals were probably the main source of animal protein. Birds were probably too small and too hard to catch–except when breeding at high densities–to be worth bothering with. The Inuit of northern Canada, for example, seemed to take birds for food only during the breeding season and only at dense colonies like those of murres and geese where eggs, offspring and adults could be gathered in numbers [3].

As Jeremy Mynott describes in his new book [4], it was not until cities and towns sprang up during what is called the Neolithic Revolution, about 5500 years ago, that humans really started to pay much attention to birds. And the rest is history, literally.

SOURCES

- Lorblanchet M (1995) Les Grottes Ornées de la Préhistoire: nouveaux regards. Paris: Editions Errance.

- Lucas AM, Stettenheim PR (1972) Avian anatomy: integument. Parts I and II. Agriculture Handbook 362. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture.

- Mynott J (2018) Birds in the Ancient World: Winged Words. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sandars N (1992) Prehistoric Art in Europe, 2nd Edition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Sieveking A, Sieveking G (1962) The Caves of France and Northern Spain: a guide. London: Vista Books.

Footnotes

- Peter Stettenheim: (1928-2013) was an expert on the integument (including feathers) of birds (see Lucas and Stettenheim 1972). He was also editor of The Condor and one of the driving forces in the establishment of the Birds of North America series, now online here

- birds in other paleolithic caves: there is a bird-like totem painted on the wall at Lascaux, but it appears to be a staff or statue with a bird figure at the top, rather than a representation of a specific bird species

- prehistoric Inuit hunting birds: see this previous post for example

- new book: see Mynott (2018), which is now in my queue of books to read and review on this blog

IMAGES: all photos from Le Portel by the author; map modified from one online here; owls at Tros-Frères from Lorblanchet (1995) available with additional information here

Bob,

All the notes and much of the resources for Peter’s work on birds & art’ projects (there were several) have been deposited in the department of ornithology at the Yale Peabody museum.

I was asked to help archive this material by the Stettenheim family.

It is being curated under the direction of Rick Prum.

I had gone through this material in some detail and there are numerous notes, materials for a course he taught occasionally in the area, but no book outline.

FYI.

Cheers,

Alan