…The Private Life of the Gannets, for Best Short Subject (One Reel). It is 1938, and this film is the first movie about wildlife to win an Academy Award. Julian Huxley was the producer and director, and Ronald Lockley was the writer. A. L. Alexander, the narrator, is listed on IMDB as the ‘star’, though the real stars of the film are the Northern Gannets of Grassholm, a small rocky islet off the western tip of Pembrokeshire, Wales.

…The Private Life of the Gannets, for Best Short Subject (One Reel). It is 1938, and this film is the first movie about wildlife to win an Academy Award. Julian Huxley was the producer and director, and Ronald Lockley was the writer. A. L. Alexander, the narrator, is listed on IMDB as the ‘star’, though the real stars of the film are the Northern Gannets of Grassholm, a small rocky islet off the western tip of Pembrokeshire, Wales.

Gannets was completed in 1934 and received a ‘special mention’ at the 3rd Venice International Film Festival in 1935. In 1937, it was picked up by a company called ‘Educational’ for distribution in the United States by 20th Century Fox. It was, apparently, one of the few ‘Educational’ films actually shown in schools, so it must have reached a wide audience of impressionable young minds. You can watch the entire 10 minutes and 39 seconds right here (expand to full screen to see the rather fuzzy details):

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lN_doZVuWEY]

The human ‘crew’ that made Gannets was decidedly world class. The production company London Films Productions was founded in 1932 by the producer-director-screenwriter Alexander Korda. Korda’s company made seven films in its first two years, one of which was The Private Life of Henry VIII, a movie that was wildly successful. In 1933, it was nominated for Best Picture at the Academy awards, and the lead actor, Charles Laughton, won for Best Actor. This was the first Academy Award won by any film made outside the United States, and it was undoubtedly the inspiration for the name of their gannet film to be released the next year, possibly trying to capitalize on the success of Henry VIII.

By 1933, Julian Huxley was a well-known and popular radio and television presenter. He and his brother Aldous were scions of the Huxley family, initially made famous by their grandfather, Thomas Henry Huxley. T. H. Huxley was a biologist who is probably best known today for his eloquent support of Darwin’s ideas following publication of The Origin of Species.

Julian began watching birds as a young boy and pursued the study of biology at school. In 1910, he got a job as Demonstrator at Oxford and began studying the courtship behaviour of grebes and redshanks. His 1914 paper on the Great Crested Grebe is landmark study in the emerging field of animal behaviour (ethology). Huxley went on to achieve greatness as one of the architects of the Modern Synthesis of evolutionary biology, as the first director of UNESCO, as one of the founders of the World Wildlife Fund, and as President of the British Humanist Association. He was knighted by the Queen in 1958.

I find it interesting that Huxley’s major studies of the courtship and mating behaviour of birds all focused on species—grebes, loons (divers), redshanks—like gannets, where the male and female are virtually indistinguishable. Possibly because he did not study birds that had extravagant male plumages, Huxley believed that courtship “ceremonies [are] just an expression of excitement and affection” as he says about gannets in the movie. He thought that Darwin’s ideas about sexual selection (and mate choice) were a mistake. His opinions were so well-regarded that he effectively put an end to the study of sexual selection for half a century [1]. His ideas about mate choice and monogamy are all the more surprising given his own sexual pecadilloes [2] .

Ronald Lockley probably provided the inspiration for the gannet movie. At the age of 24, he leased Skokholm, a small island 14 km east of Grassholm. Taking out a lease for 21 years, he moved there with his new wife, intending to sell rabbits that he caught or raised. He soon found he could earn more by writing, and over his lifetime published more than 60 books and myriad articles about seabirds, in particular, and natural history in general. In 1933, five years after moving to Skokholm, he established on the island the first bird observatory in the UK, and continued to conduct pioneering research on the island’s seabirds. The Lockley’s were forced to move to the Welsh mainland at the start of WWII.

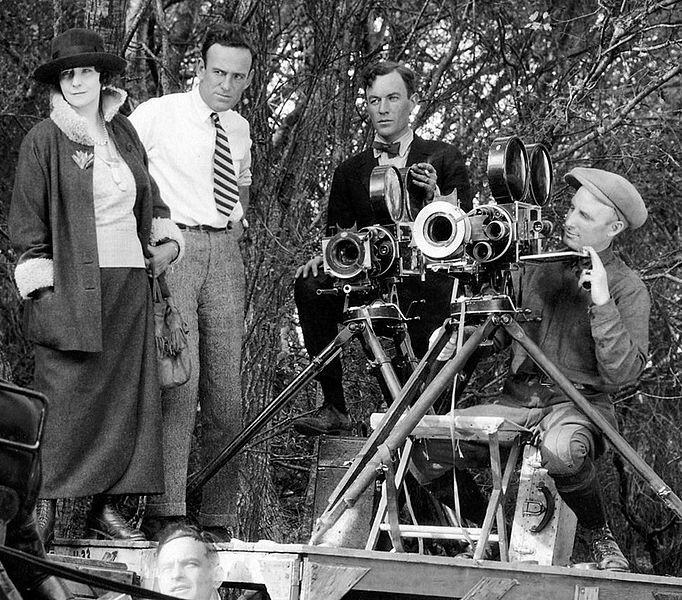

The cinematographer, Osmond Borradaile (behind the camera, below), was a Canadian from Manitoba. He got his start making silent films in Hollywood, but soon specialized in outdoor photography ‘on location’. In 1939 he shared the Academy Award for cinematography for his (outdoor) work on the film The Four Feathers. In the 1930s he began working for Korda’s London Films Productions, and so was an obvious choice for filming the gannets as he loved adventure and wild places. To capture the impression of a gannet returning to the colony, for example, he filmed from a Supermarine Stranraer flying boat as it power-dived toward the island.

It was Oscar night again last night, but no wildlife films were in the running. And no, the short film Animal Behaviour is not about wildlife, nor is Black Panther, Black Sheep or Isle of Dogs. A few wildlife films have, however, won an Oscar since 1938, though not always as good as Gannets in depicting and interpreting wildlife behaviour accurately [3]. The next nature film to win an Academy Award for Best Documentary [4] was The Sea Around us in 1952, followed by The Living Desert (1953), The Vanishing Prairie (1954), The Silent World (1956), White Wilderness (1958), Serengeti Shall Not Die (1959), World Without Sun (1964), and March of the Penguins (2005).

As good as Gannets was in its day, television has brought us an endless stream of superb wildlife cinematography since the 1980s, from NATURE on PBS with George Page and many National Geographic specials to the myriad BBC Natural History Unit productions and David Attenborough‘s Life series (on Earth, of Birds, of Mammals, Underground, in Cold Blood, on Land, in the Undergrowth), Planet series, and Dynasties series. I expect that the popularity of nature films on TV from the 1970s until today can account, at least in part, for the fact that only one wildlife documentary film to be shown in theatres has won an Academy Award since 1964.

SOURCES

-

Bartley MM (1995) Courtship and continued progress: Julian Huxley’s studies on bird behavior. Journal of the History of Biology 28:91–108.

-

Birkhead TR, Wimpenny J, Montgomerie R (2014) Ten Thousand Birds: Ornithology since Darwin. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

-

Darwin C (1859) On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. London: John Murray.

- Huxley J (1912) The Great Crested Grebe and the idea of secondary sexual characters. Science 36: 601-602.

-

Huxley JS (1914) The courtship-habits of the great crested grebe (Podiceps cristatus); with an addition to the theory of sexual selection. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 35:491–562.

-

Lockley RM (1936) Skokholm Bird Observatory. London: Macmillan.

- Nelson JB (2005). Pelicans, Cormorants and their relatives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Footnotes

- Huxley and sexual selection: see Birkhead et al. 2014 pages 332-337

- sexual pecadilloes: see Birkhead et al. 2014 pages 335-337

- depicting wildlife behaviour accurately: The Disney films, for example, were well known for nature fakery in the pursuit of a sensational, even if apocryphal, story. Gannets is very accurate with respect to what was known at the time, though whoever/whatever made the closed captions made some amusing errors. The written text in the closed captions, for example, says of the courtship that “the long beaks click against one another like rapists”!

- Best Documentary: this category was established in 1941, replacing the award for Best Short Subject that Gannets won

IMAGES: Lockley’s house and Osmond Borradaile from Wikipedia; gannets at Cape St Mary’s by the author

Lovely, thanks. I’m a Huxley fan. Off to read about Julian peccadilloes! BTW, he said rapiers, not rapists . . .

Yes, of course, the narrator said ‘rapiers’ but the closed captioning translated this as ‘rapists’. There are a few other amusing mis-captionings but this one was the best. It’s hard not to be a Huxley fan, he did so much, so well.

Nice post, as ever. And don’t forget that Julian Huxley started the biology department at Rice University. He found Houston so hot and mosquito-filled that he chose to return to England as WWI was beginning. He also wrote an influential book on individuality at that time.

Which is why Julian Huxley’s archives are at Rice and not in Britain.