I suspect that rather few birders or ornithologists have heard of, or know much about, Erwin Stresemann. Among his many accomplishments Stresemann wrote the first and most comprehensive history of ornithology, published originally in German in 1951 (Die Entwicklung Der Ornithologie von Aristotles bis zur Gegenwart) and then (thankfully for me) in English in 1974 as Ornithology: from Aristotle to the Present.

I suspect that rather few birders or ornithologists have heard of, or know much about, Erwin Stresemann. Among his many accomplishments Stresemann wrote the first and most comprehensive history of ornithology, published originally in German in 1951 (Die Entwicklung Der Ornithologie von Aristotles bis zur Gegenwart) and then (thankfully for me) in English in 1974 as Ornithology: from Aristotle to the Present.

Stresemann’s book does pretty well what its title says, covering the entire vast sweep of ornithology from its origins in Ancient Greece to ‘the present’ (i.e. 1951), or with respect to American ornithology up to the early 1970s. The extension to the 1970s was a consequence of Stresemann’s long friendship with Ernst Mayr who contributed a final chapter. modesty entitled Epilogue: Material for a History of American Ornithology. This title belied Mayr’s extraordinary scholarship and broad grasp of the history of science (see his magnificent The Growth of Biological Thought). Stresemann did not live long enough to see the publication of the English edition but, as Mayr says in the foreword, he knew about it.

Stresemann’s book does pretty well what its title says, covering the entire vast sweep of ornithology from its origins in Ancient Greece to ‘the present’ (i.e. 1951), or with respect to American ornithology up to the early 1970s. The extension to the 1970s was a consequence of Stresemann’s long friendship with Ernst Mayr who contributed a final chapter. modesty entitled Epilogue: Material for a History of American Ornithology. This title belied Mayr’s extraordinary scholarship and broad grasp of the history of science (see his magnificent The Growth of Biological Thought). Stresemann did not live long enough to see the publication of the English edition but, as Mayr says in the foreword, he knew about it.

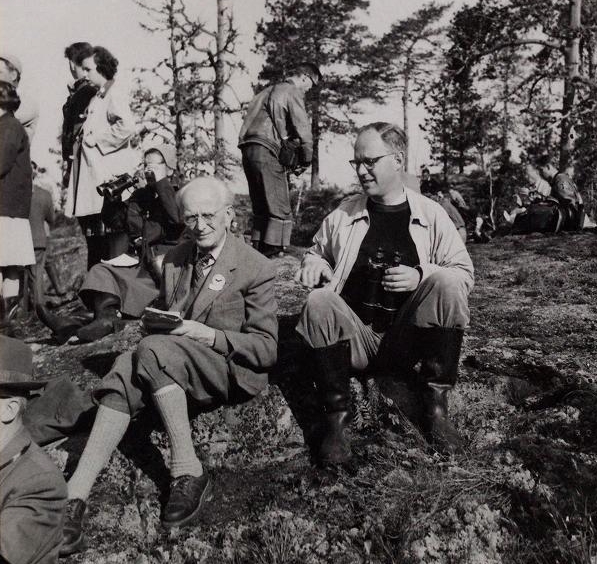

Stresemann is poorly known outside his native Germany, where he is an ornithological hero. He wrote almost entirely in German and I am sure that that, together with his nationality and rather formal manner, isolated him from many English and North American ornithologists, especially in the aftermath of WWII. However, it is essential to note that Stresemann opposed the regime in Germany during war and sent bird rings (bands) and other materials to British and American ornithologists incarcerated in German prison camps. Stresemann’s story and extraordinary contribution to ornithology was championed by my late friend Jürgen Haffer in some excellent papers [1].

An important reason why Stresemann is not better known is the lack of an English translation of the book that launched his career in Germany: the volume simply entitled Aves [Birds] in the Handbuch der Zoologie (edited by Willy Kükenthal) published in 1927-34. If you have a chance to look at this—even, if like me, you are unable to read German—you cannot fail to be impressed by the breadth and depth of the coverage of all aspects of ornithology — a staggering achievement that Stresemann was asked to produce when he was only 25 years old. His work on Aves was delayed by WWI but he started writing right after the war and sent the first installment of his manuscript to Kükenthal in 1920

Equally staggering is Stresemann’s book on the history of ornithology, written largely from memory in a tiny apartment during the years immediately following the end of WWII. This was an era referred to as the ‘hunger blockade’ during which Stresemann and his family had no electricity or gas, no heating, and no access to libraries. Extraordinary!

I re-read some of Stresemann’s Ornithology recently, and wondered how his book might be reviewed had it been published now. First, no one could challenge his scholarship. Inevitably—notwithstanding the excellent translation by Hans J and Cathleen Epstein and editing by G. William Cottrel—the text now seems a bit dated, but this is no impediment. Language evolves, and one has to adjust one’s expectations, just as one should adjust one’s expectations about the way science was conducted in the past [2].

Second, one could legitimately say that Stresemann was somewhat biased towards German-speaking ornithologists. However, central Europe was where a huge amount early ornithology was conducted, and Stresemann’s account makes that material readily accessible to non-German speakers.

Third, and particularly impressive to my mind, is the sheer volume of information that Stresemann was able to access and describe. Only fifteen years ago when I started the research for my own first book on the history of ornithology, The Wisdom of Birds, I had to visit libraries in Oxford, Cambridge, across Europe and North America to see particular books. A few years later, much I what I had consulted was available on-line. Stresemann (obviously) had no internet, and even though he had access to an excellent library at the natural history museum in Berlin where he worked, his scope was extraordinary.

Finally, re-reading Stresemann’s text, I could not help but be impressed by his wonderful grasp of history; his ability to put himself in the position of his predecessors and place ornithological history in its proper context.

SOURCES

- Haffer, J (1994) The genesis of Erwin Stresemann’s Aves (1927–1934) in the Handbuch der Zoologie, and his contribution to the evolutionary synthesis”. Archives of Natural History 21: 201–216.

- Haffer J (2008) The origin of modern ornithology in Europe. Archives of Natural History 35: 76–87.

- Haffer J, Rutschke E, Wunderlich K, editors (2004) Erwin Stresemann (1889-1972): Leben and Werk eines Pioniers der wissenschaftlichen Ornithologie [in German with English summary]. Acta Historica Leopoldina 34: 1-468.

- Kruuk H (2003) Niko’s Nature: The Life of Niko Tinbergen and His Science of Animal Behaviour. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mayr E (1982) The Growth of Biological Thought. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

-

Stresemann E (1927-34) Sauropsida: Aves. In W. Kukenthal & T. Krumbach (Eds.), Handbuch der Zoologie. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co.

- Stresemann E (1951) Die Entwicklung der Ornithologie von Aristoteles bis zur Gegenwart. Berlin: F. W. Peters

- Stresemann E (1975) Ornithology from Aristotle to the Present. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

- ten Cate C (2009a) Niko Tinbergen and the red patch on the herring gull’s beak. Animal Behaviour 77: 785-794

- ten Cate C (2009b) Tinbergen revisited: a replication and extension of experiments on beak colour preferences of herring gull chicks. Animal Behaviour 77: 795-802.

Footnotes

- papers about Stresemann: see Haffer 1994, 2008, Haffer et al. 2004

- science in the past: see ten Cate 2009a, b, for example

IMAGES: of Stresemann from Wikimedia, both in the public domain; book covers from Amazon.de (German edition) and R Montgomerie (English edition)