By Ken Rosenberg

Linked paper: Untangling cryptic diversity in the High Andes: Revision of the Scytalopus [magellanicus] complex (Rhinocryptidae) in Peru reveals three new species by N.K. Krabbe, T.S. Schulenberg, P.A. Hosner, K.V. Rosenberg, T.J. Davis, G.H. Rosenberg, D.F. Lane, M.J. Andersen, M.B. Robbins, C.D. Cadena, T. Valqui, J.F. Salter, A.J. Spencer, F. Angulo, and J. Fjeldså, The Auk: Ornithological Advances.

Unraveling the mysteries of Neotropical bird diversity has captured the attention of scientists for more than 100 years. Well into the 21st Century, new species of birds are still being found. Many newly described birds are so-called cryptic species, which look so much like other, already-recognized species that they’ve remained “hidden in plain sight” until careful attention to vocalizations, behaviors, or new molecular analyses revealed their existence.

Contrary to popular notion, the vast majority of Neotropical birds are “little brown jobs”— just open any South American field guide to plate after plate of look-alike woodcreepers, spinetails, or tyrannulets. Even among these challenging birds, one group stands out as almost impossibly indistinguishable: the small mouse-like birds known as tapaculos. With most Andean tapaculos placed in a single large genus, Scytalopus, the number of known species within this genus has grown steadily from 10 in 1951 to 44 in 2019. Our study adds three new species, all endemic to Peru, highlighting the continued potential of this complex geographical region to change our understanding of avian diversity and speciation. Our story spans 40 years of field and lab work by multiple research teams, combining traditional specimen-based comparisons with the latest DNA sequencing and analysis of community-shared birdsong archives into an integrative framework for taxonomic study.

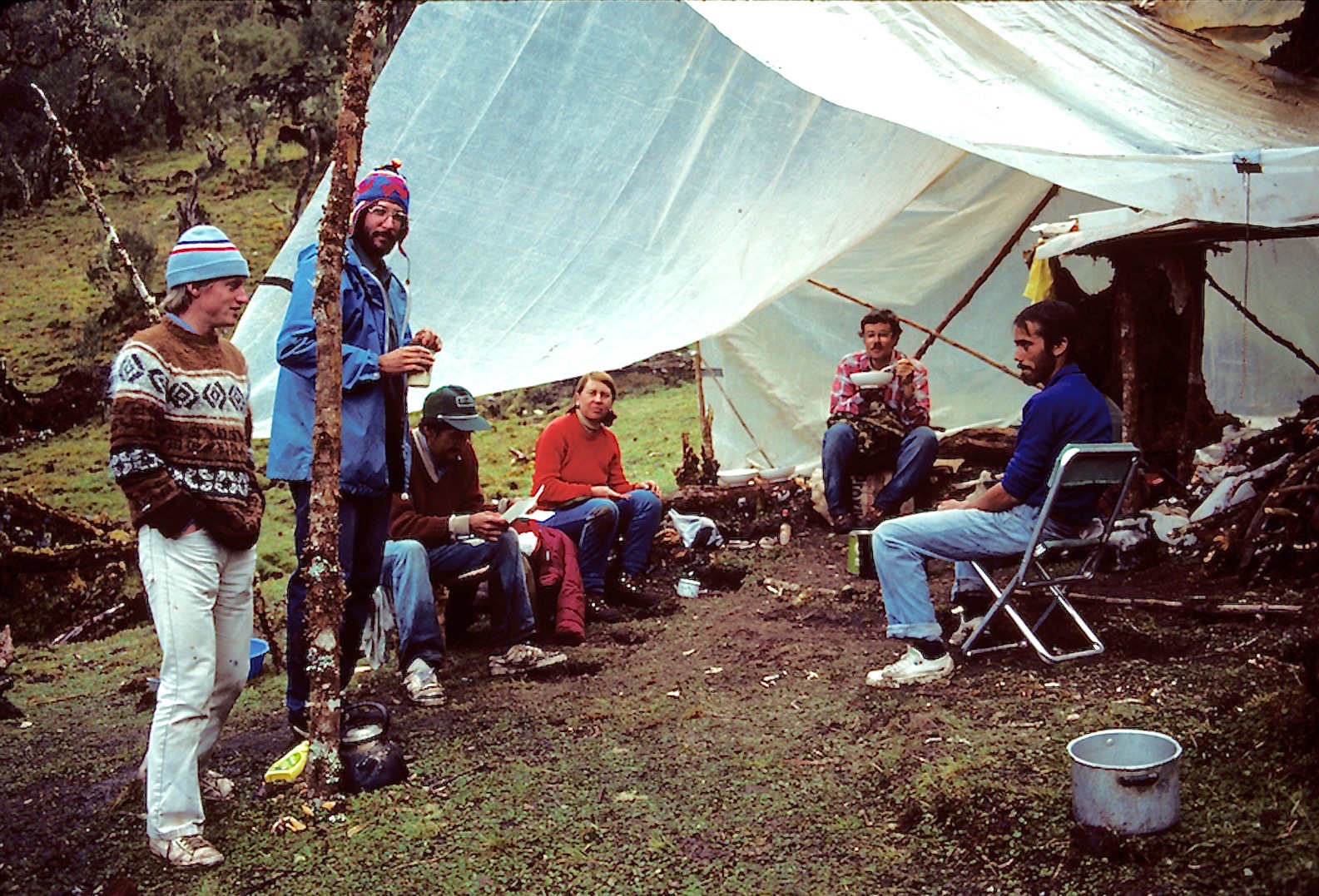

When I arrived at Louisiana State University’s Museum of Natural Science in 1985, John O’Neill was staring at maps of Peru, decades before Google Earth, strategically plotting the destination of LSU’s next expedition to the Andes with the hope of continuing a spate of new species discoveries. In July, I set out with fellow students Tristan Davis and Gary Rosenberg on a trek by truck, foot, and mule to a semi-isolated spur of eastern Andean tree-line forest in Huánuco. We were joined by O’Neill and Tom Schulenberg, as well as Peruvian ornithologists Irma Franke and Enrique Ortíz. A particular focus was documenting the precise distributions of several hard-to-detect species complexes, including tapaculos, with modern specimens, sound recordings, and the first-ever tissue samples, which we deposited in a 100-pound liquid nitrogen tank carefully hauled to our remote campsite on the back of a mule.

As we worked an elevational gradient from 2100 meters to 3800 meters, we had confidently identified four expected taxa of Scytalopus. It was thus a big surprise when a very different-looking (for a tapaculo) bird appeared in the rocky bunchgrass habitat above treeline — one more species of Scytalopus than we had a name for. We immediately suspected a new species; with its overall silvery coloration, broad whitish eyebrow, and wavy cinnamon barring on the flanks and tail, this was the most distinctive of the five tapaculos on our transect. Back at LSU, however, we discovered a great deal of confusion in the literature, dating back to early 20th century, regarding the application of species names to Peruvian tapaculos. In other words, as certain as we were that we had found an undescribed species, developing a formal description and determining its affinities among the Andean Scytalopus complex would need to wait.

Also in the 1980s, an independent research team from the University of Copenhagen that included Jon Fjeldså was studying high-elevation birds throughout the Andes. Between 1987 and 1989, they had similar encounters with an undescribed tapaculo in the mountains of southern Peru, at Bosque Ampay in Apurímac. It was clearly a member of the pale-browed, above-treeline complex of Scytalopus tapaculos, but as with our bird from Huánuco, the “Ampay tapaculo” has remained for decades without a formal description and name. In their seminal 1990 volume, Birds of the High Andes, Fjeldså and Niels Krabbe proposed that most previously described geographic variants across the Andean tapaculos deserved separate species status, and they provided the first published descriptions of plumage and voice of the two still-undescribed Peruvian taxa.

Fast forward nearly 30 years. New research teams from the University of Kansas, the University of New Mexico, and Peruvian institutions CORBIDI and Universidad Mayor de San Marcos made significant collections and contributions to our understanding of Andean birds. A re-examination of tapaculo holotypes by Niels Krabbe, some collected as early as the 1840s, clarified the links between names and taxa. Dozens of professional and amateur ornithologists deposited audio recordings in community-shared archives at Xeno-canto and Cornell’s Macaulay Library, facilitating a new analysis of tapaculo vocalizations. Recent eBird observations were helping to clarify the known distributions of both new taxa, still lacking formal names. The real breakthrough came when Daniel Cadena at the Universidad de los Andes in Colombia and colleagues completed the first comprehensive DNA analysis of the entire genus Scytalopus. Finally, we had a roadmap for preparing the formal descriptions.

Our current paper brings together multiple research teams and individuals instrumental to completing the tapaculo puzzle. An integrated framework of morphological, vocalization, and genetic analysis finally puts our species descriptions in their proper context. As with most complex studies, as many new questions were generated as answers. A serendipitous moment occurred when we realized that some puzzling vocal and morphological variation actually corresponded with a distinct (and also puzzling) genetic lineage in Cadena’s phylogeny — a third new tapaculo species right in front of our noses! To clinch this newest discovery, we obtained DNA sequences from the dried toepads of nine historic specimens, including several collected almost a century ago, and aligned these with Cadena’s dataset. Finally, a complete picture of three new species and their closest relatives across the Peruvian Andes emerged. By placing these cryptic gray pieces of the tapaculo puzzle, our study provides a tiny window into the still-underappreciated diversity of Andean birds.

This is one of the greatest publications and biodiversity stories. And inspiring! I’m proud of LSU where I received my MS. Plus, tapaculos are my fave groups of birds.