After a seminar last week, my colleague Jannice Friedman, a botanist, asked me if ‘oology’ was really a word, as it had appeared on one of the speaker’s slides. So, she asked, what is the ‘o’ that ‘ology’ (the study of) has been tacked on to? I explained to her that oology (or oölogy) is the study of eggs, and birds’ eggs in particular, but I had no idea why it was not something more logical like ‘ovology’ [1]. Oology is one of those words like ‘popsicle’ and ‘’castle’ that are familiar but then sound ridiculous when you think about them or repeat them too often [2].

The OED says that oology first appeared in print in English in 1830, in an advertisement [3] for the soon-to-be-published British Oology by William Hewitson. Hewitson published this ‘book’ as a series of fascicles, sold by subscription beginning in 1831 and completed in 1838. The second (1843-44) and third editions (1856) were called Coloured Illustrations of the Eggs of British Birds. Among the subscribers to that first edition were such notables as John James Audubon, John Gould, W. J. Hooker, Sir William Jardine, Prideaux John Selby, and William Yarrell [4]. It was clearly a popular publication on a popular topic.

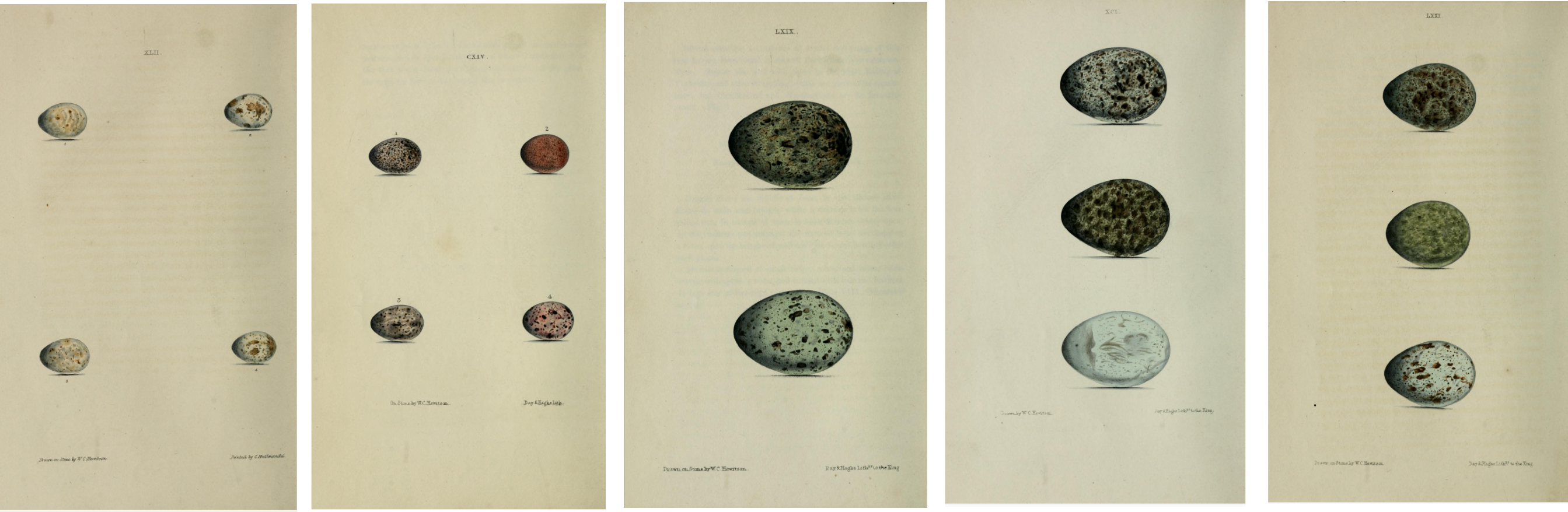

Hewitson’s British Oology starts with an Introduction in which he waxes poetic about his love of Nature, and the pleasures of egg-collecting: “who does not remember those joyous times when, at the first breaking loose from school, he has hied him to the wood and the hedge-row, in search of his painted prize?”[5] In that first edition, he describes the eggs and nests of 229 species that bred in Britain, illustrated with coloured plates that he drew on lithographic stone and then hand-coloured. Those plates, curiously, show no more than four eggs per page, all life size, and thus the plates are often mostly white space (see below).

Like most pre-Darwinian naturalists, Hewitson saw in the design of eggs some God-given purpose for the good of mankind: “For the same purpose for which they adorn the plumes of the Humming-bird, or the wing of the resplendent butterfly — to gladden our eyes, ‘To minister delight to man, to beautify the earth.’ And thus it is that the eggs of nearly all those birds (the Owl, Kingfisher, Bee-cater, Holler, Nuthatch, and the Woodpeckers) which conceal them in holes, are white, because in such situations colour would be displayed to no purpose.” [5].

Even in the interspecific variation in clutch size, Hewitson saw the hand of God providing for mankind: “In every instance we shall find the same beneficent influence acting for our welfare; increasing rapidly, by the number of their eggs, those species which are of the greatest use to us, and bestowing upon those intended for our more immediate benefit, a most wonderful power of ovo-production; and at the same time curtailing in their numbers those species which, in their greater increase would soon become injurious to us.” [5]

Despite all of that teleology, Hewitson was perceptive in noting that species with precocial offspring have eggs that are larger relative to female size compared to species with altricial hatchlings. He also concludes that egg colour cannot be generally useful for camouflage except in a few ground-nesting birds. With respect to the use of eggs in taxonomy, he has a mixed message but still seems to want to cling to the idea that egg traits will be useful for classification [6]. His descriptions of breeding habitats, nest construction, breeding seasons and clutch sizes provide a useful window on the state of knowledge about British birds almost two centuries ago.

I assume that the word ‘oology’ was already in general use when Hewitson published British Oology because he uses the term without definition or special mention, as if all readers would know what he was talking about. For the next century oology was a prominent topic among people interested in birds, the subject of several books, myriad papers, and even a museum of oology [7] in Santa Barbara, California. Hewitson later turned his attention to collecting and illustrating lepidoptera, but occasionally dabbled in oology, mainly updating his British Oology with papers on new discoveries in the British Isles and continental Europe.

So where did that word ‘oology’ come from? The OED says that it is a combination of ‘oo’ and ‘logy’ but that really does not make sense to me as ‘ology’— not ‘logy’—is the standard suffix meaning ‘the scientific study of’. For example, Wikipedia lists 342 ‘ologies’ all of which appear to append ‘ology’ onto a subject of study: bi-ology, ichthy-ology, ornith-ology. The OED also says that ‘oologia’ is the Latin version first used in 1691, probably derived from ‘oion’ Greek word for egg. My guess is that it’s a word that egg collectors made up to give their hobby a patina of science.

The word ‘oology’ became associated with egg-collecting in the Victorian era but largely disappeared from the ornithological literature in the 1920s, probably because egg-collecting fell out of favour (and was eventually outlawed). The study of eggs waxed and waned throughout the twentieth century with a monumental book—The Avian Egg—by AL and AJ Romanoff published in 1949 being one of the highlights. Over the past decade or so, the study of bird’s eggs has enjoyed a resurgence with new tools available for measuring colours and shapes but few ornithologists use the word oology any more.

SOURCES

- Anonymous (1908) Mr. W. C. Hewitson. The Ibis Jubilee Supplement 2: 182–185.

- Birkhead T (2016) The Most Perfect Thing: Inside (and Outside) a Bird’s Egg. Bloomsbury USA.

- Hewitson WC (1831-38) British oology: being illustrations of the eggs of British birds, with figures of each species, as far as practicable, drawn and coloured from nature : accompanied by descriptions of the materials and situation of their nests, number of eggs, &c. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Charles Empson [first edition available here]

- Hewitson WC (1859) Recent discoveries in European oology. The Ibis 1: 76-80

- Kiff L (2005) History, present status, and future prospects of avian eggshell collections in North America. The Auk 122: 994–999,

Footnotes

- ovology: is, according to the dictionary, one variant of oology but I have seen it in print

- sound ridiculous when you think about them or repeat them: this is called semantic satiation or wordnesia and can happen with any word

- advertisement: in Magazine of Natural History 3 (end matter)—”On the First of January, 1831, will be published, the First Number of British Oology, being illustrations of the Eggs, Nidification, &c. of British Birds“

- subscribers to British Oology: the full list is at the beginning of the first edition.

- Hewitson quotations: from Hewitson 1831 pages 3, 8, and 8-9, respectively

- useful for classification: this idea persisted well into the 20th century despite ample evidence that it eggs were not a useful trait for taxonomy. I expect that some of this persistence was driven by a desire to justify the collecting of eggs

- museum of oology: the Museum of Comparative Oölogy was started by William L. Dawson in 1916, and is now part of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History

“My guess is that it’s a word that egg collectors made up to give their hobby a patina of science.” Agree. You used Occam’s razor, the OED did not!

Our first book of eggs was 1948 – Priests Eggs of Southern African Birds.

http://weavers.adu.org.za/newstable.php?id=267

Thanks for that reference. I really want to write more about the history of ornithology in Africa, Australia/New Zealand, and Asia, and will try to do a post on that Priest book in the coming weeks.

I’d start with the fitztitute!

‘http://www.fitzpatrick.uct.ac.za/fitz/contacts’