For the past week or so the internet has been abuzz about a cockatoo depicted 4 times in the margins of Frederick II’s De Arte Venandi cum Avibus written around 1245 CE [1]. The story is that this bird suggests a mediaeval trade route from Australia to Italy, overturning the Eurocentric notion that Australia was a dark continent until ‘discovery’ by Dutch sailors early in the 17th century. This story has already been retweeted about 2000 times on Twitter, and has appeared in the popular press worldwide, including CNN, Reuters, ABC (Australia), Japan Times, and The Guardian [2].

This story began with an original paper published last month in the journal Parergon [3] by Heather Dalton, Jukka Salo, Pekka Niemelä and Simo Örmä. That paper is wonderfully detailed about the creation and provenance of De Arte, about the source of Frederick’s cockatoo, and the details of the four coloured drawings of the cockatoo in the surviving copy of the original manuscript housed in the Vatican Library in Rome [4]. The popular press has been remarkably accurate in reporting the details of that paper, avoiding the hyperbole and small misleading errors that too often characterize science journalism.

Here, in a nutshell, are 5 quotes that summarize what I think are the important features of this story:

-

Frederick II “Frederick II of Sicily made contact with the Kurdish al-Malik Muhammad al-Kamil in 1217… The two rulers communicated regularly over the following twenty years, exchanging letters, books and rare and exotic animals….[like] the Sulphur-crested or Yellow-crested Cockatoo the sultan sent Frederick.” [5]

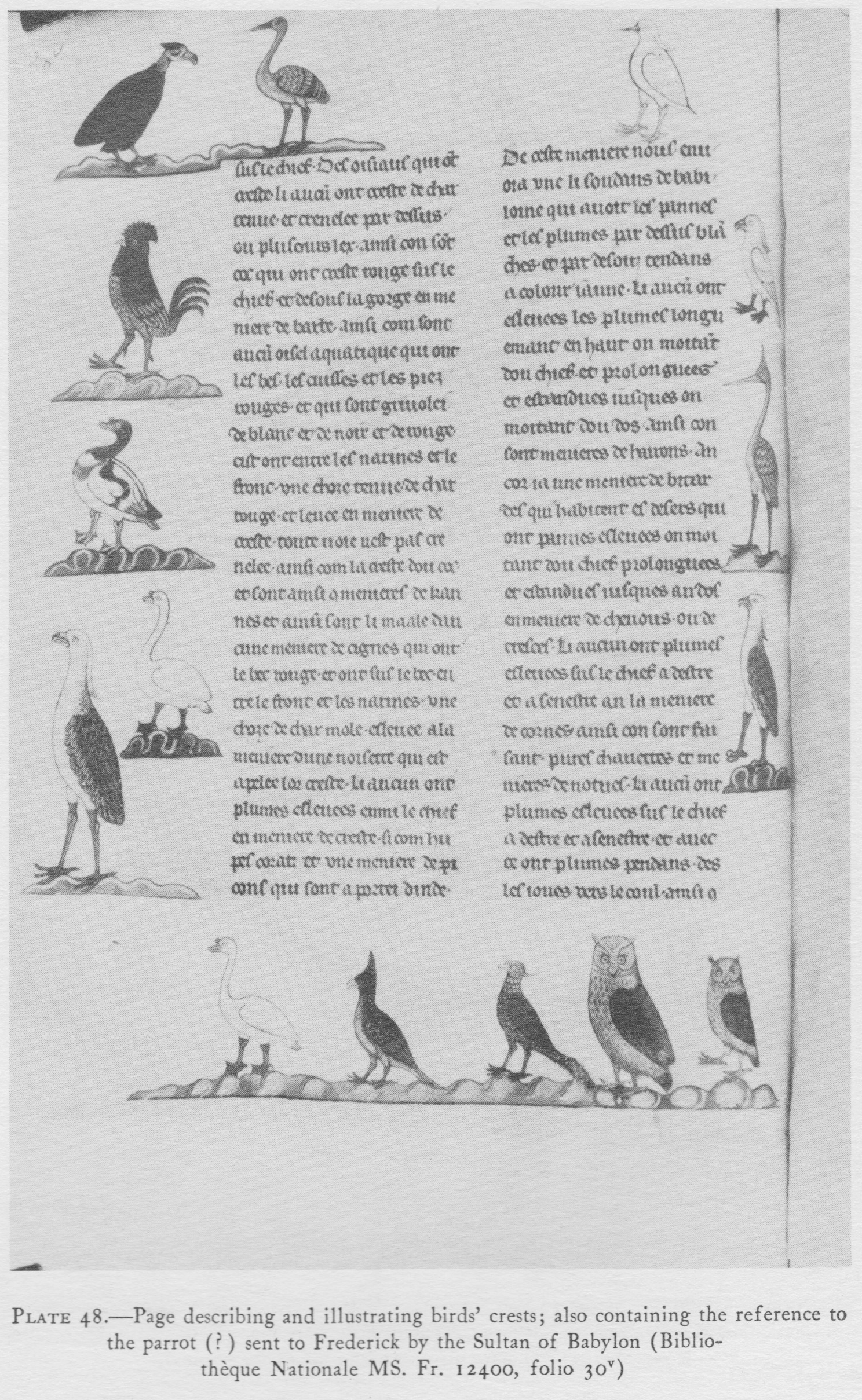

- “De arte was written in Latin by Frederick or a scribe under his direction between 1241 and 1244…Amongst the nine hundred marginal illustrations of birds, animals, falconers, perches, and falconry equipment are four coloured drawings of the white cockatoo gifted to Frederick II.” [5]

- “Discovery of earliest European depiction of cockatoo in medieval book rewrites history of global trade” [6] see also quote 7

- “Because the four images in the Vatican manuscript have rarely been reproduced in print, few people are aware of their existence. This may be because many scholars have relied on Casey Albert Wood and Florence Marjorie Fyfe’s 1943 English translation of all six books of the De arte. 11 Although Wood and Fyfe included many illustrations from the Codex Ms. Pal. Lat. 1071, they did not include those of the cockatoo. [5]

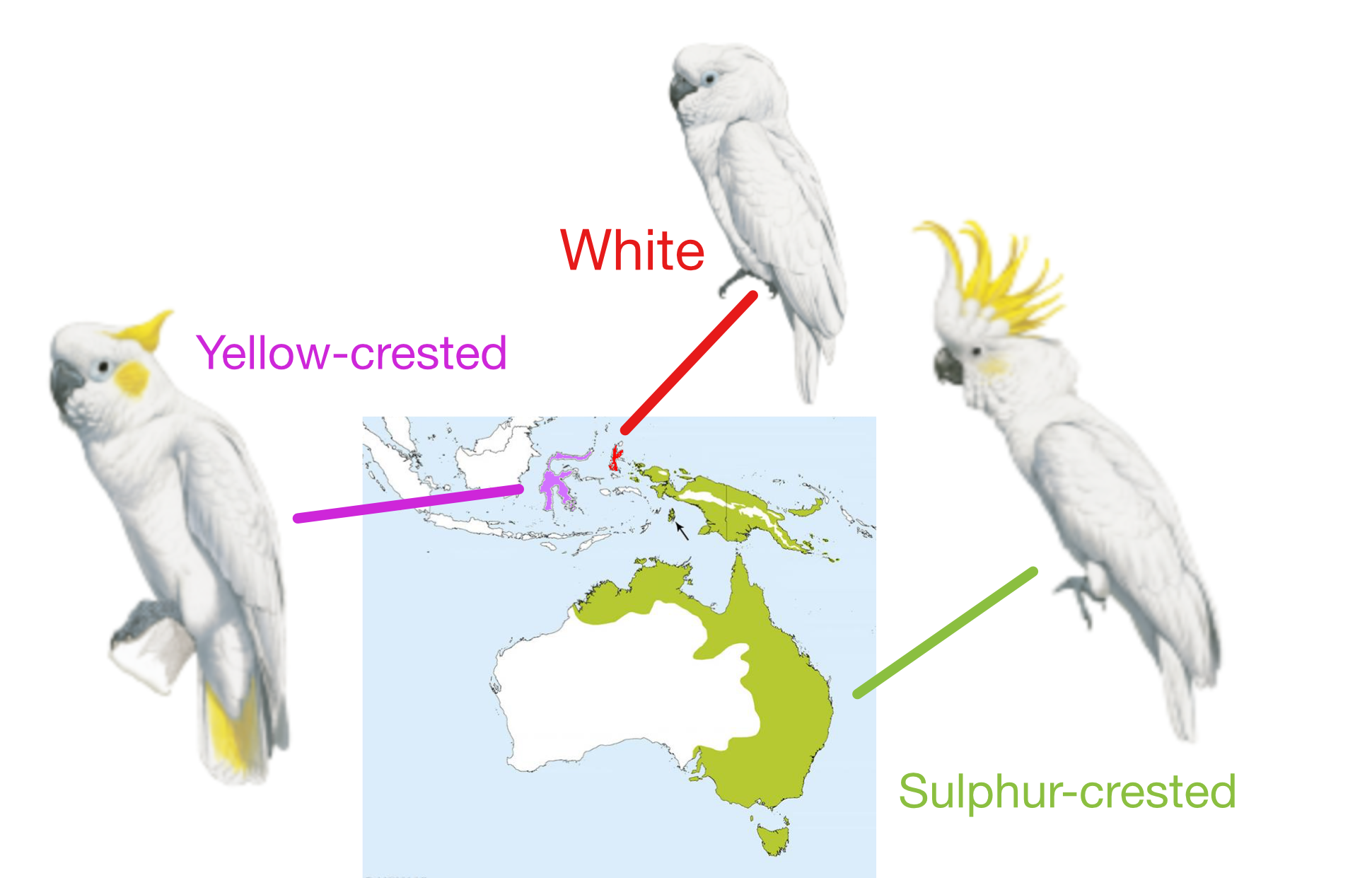

- “Bearing in mind the shape of the crest, the blue/grey of the periophthalmic ring and the lack of a yellow tinged ear patch, Frederick’s cockatoo was in all likelihood a Triton Cockatoo…or one of the three subspecies of Yellow-crested Cockatoos that have a yellow crest.” [5]

- “The main significance about it is we tend to think of our region, not just Australia, but the islands around it, as the very last things to be discovered; the European view is it’s almost this dead continent and nothing was happening until Europeans discovered it.” [7]

While Dalton and colleagues have done a great job summarizing all of the details in their paper, I do have a few quibbles with the final four points listed above. I was, for example, a little surprised to hear of the ‘discovery’ of these cockatoo drawings because I certainly knew about them. As so often happens, I wondered if I had simply failed to realize their significance.

But as the paper so nicely summarizes, previous authors [8] had written about the cockatoos, so this new work might be better characterized as a re-discovery. In fairness, Dalton and colleagues never claimed this to be a new discovery but this is the way that most of the popular press has characterized their work.

They do claim (point 4), however, that modern scholars are generally unaware of these illustrations, largely because everyone reads Wood and Fyfe’s translation from 1943. But that’s how I knew about the cockatoo—one of the pages (folio 18v) with the cockatoo in the margin is reproduced, albeit in black and white, on page 38 in Wood and Fyfe’s book. In the caption they even say “also containing the reference to the parrot (?) sent to Frederick by the Sultan of Babylon”, and in a footnote on page 59 they say it was likely a cockatoo from the Sunda Islands.

Dalton and colleagues do a really nice job of describing the four coloured marginal drawings and they use those details to try to identify the bird. They make the reasonable conclusion that it was likely a female Sulphur- or Yellow-crested Cockatoo. Others have suggested that it might be a White Cockatoo [8]. Nonetheless, I cannot agree with the authors’ assumption that those descriptions are very useful for identification.

For example, in the De Arte illustrations, it looks like the birds have yellowish flanks and back, whereas none of the potential cockatoos have that colouring [9]. They also interpret the shape of the crest as ruling out the White Cockatoo, but the shape and size of the bill, feet, and wing feathers are so inaccurate that I would not be inclined to assume that the crest is correctly drawn. Moreover, none of the illustrations in De Arte show the characteristic yellow cheek patch of the Yellow- and Sulphur-crested.

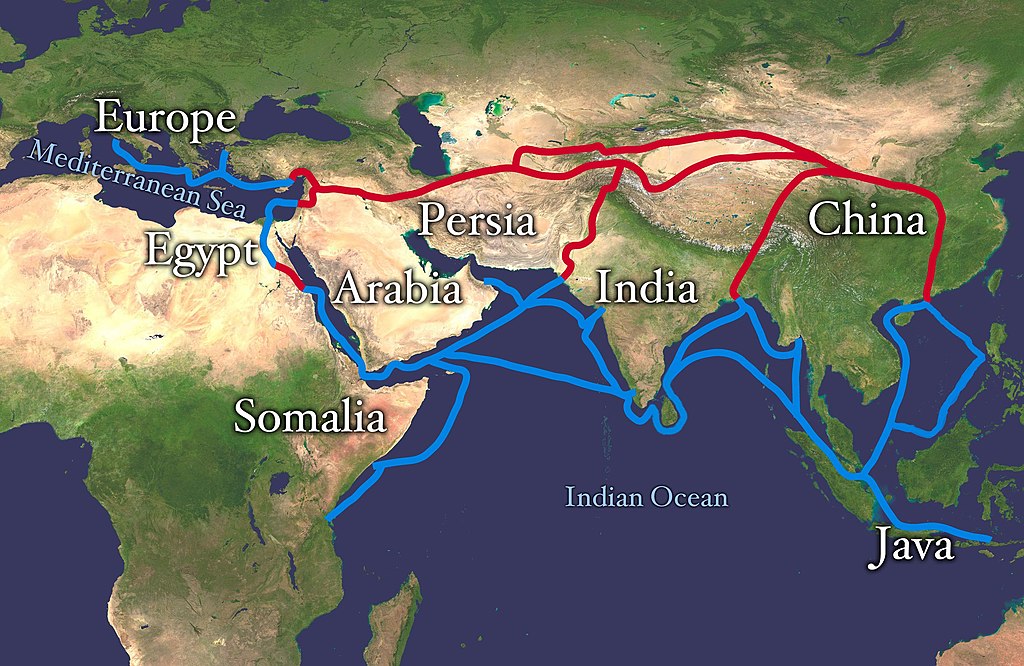

The marginal drawings are, after all, crude by modern standards, as you can see from the reproductions above. The manuscript has at least 7 marginal drawings of peacocks [10], for example, that show that, although the artist was remarkably good for his day, he was no Lars Jonsson. Thus it would be entirely reasonable for Frederick’s bird to be a White or Yellow-crested Cockatoo, from Sulawesi (one of the Sunda Islands) or the Moluccas [11]. If that is correct then I am not so sure that this cockatoo really tells us anything about mediaeval trade routes.

The marginal drawings are, after all, crude by modern standards, as you can see from the reproductions above. The manuscript has at least 7 marginal drawings of peacocks [10], for example, that show that, although the artist was remarkably good for his day, he was no Lars Jonsson. Thus it would be entirely reasonable for Frederick’s bird to be a White or Yellow-crested Cockatoo, from Sulawesi (one of the Sunda Islands) or the Moluccas [11]. If that is correct then I am not so sure that this cockatoo really tells us anything about mediaeval trade routes.

It has long been known that there was extensive trade between southeast Asia and the Middle East along the Silk Road, beginning centuries before Frederick’s day. That ‘road’ includes several marine routes extending as far east as Sulawesi and the Sunda Islands (see map below). While there may have been some trade between New Guinea and northern Australia in the 13th century, there is really no evidence for this, as far as I know. Thus, Australia does seem to have been a relatively ‘dark continent’ until the 17th century, especially to Europeans, and Frederick’s cockatoo does not really shed any light on that narrative.

I feel that I should emphasize how much I enjoyed the original article by Dalton and colleagues, despite my reservations above. In my view, science progresses when there is some healthy skepticism, and that’s what I have tried to present here.

NOTE: I accidentally posted an incomplete version of this essay a couple of days ago. My apologies for that. I blame the heat.

SOURCES

-

Dalton H, Salo J, Niemelä P, Örmä S (2018) Frederick II of Hohenstaufen’s Australasian Cockatoo: Symbol of Detente between East and West and Evidence of the Ayyubids’ Global Reach. Parergon 35: 35-60.

- Frederick II (~1245) De arte venandi cum avibus. Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, codex Ms. Pal. Lat. 1071.

- Kinzelbach R (2008) Modi auium – Die Vogelarten im Falkenbuch des Kaisers Friedrich II’. pp 62–135 in Vol 2 of Kaisers Friedrich II 1194–1250: Welt und Kultur des Mittelmeerraums (ed. Ermete K, Mamoun Fansa M, and Carsten Ritzau C). Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

- Rowley, I. (2018). Cockatoos (Cacatuidae). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (retrieved from https://www.hbw.com/node/52255 on 2 July 2018).

-

Stresemann E (1975) Ornithology from Aristotle to the present. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

-

Willemsen CA (1980) Das Falkenbuch Kaiser Friedrichs II. Nach der Prachthandschrift in der Vatikanischen Bibliothek. Dortmund: Harenberg.

-

Wood CA, Fyfe FM (1943) The Art of Falconry; Being the De Arte Venandi cum Avibus of Frederick II of Hohenstaufen by Frederick the Second of Hohenstaufen. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Yapp WB (1983) The illustrations of birds in the Vatican manuscript of De arte venandi cum avibus of Frederick II. Annals of Science 40: 597–634

Footnotes

- Frederick II’s manuscript: see my earlier post on this ornithologically important masterpiece here

- articles in popular press: but curiously not (yet) The New York Times or any of the other leading American and Canadian news media outlets.

- Parergon: is the journal of the Australian and New Zealand Association of Medieval and Early Modern Studies (Inc.), and has been publishing refereed articles since 1983.

- Frederick’s manuscript in the Vatican Library: is also available for study online in two spectacularly reproduced digital copies here and here.

- Quotations 1, 2, 4 & 5: from Dalton et al. 2018

- Quotation 3: from the headline in The Telegraph (UK)

- Quotation 6: Helen Dalton quoted in The Guardian (UK)

- previous authors on this cockatoo: see, for example, Wood and Fyfe (1943), Stresemann (1975), Willemsen (1980), Yapp (1983), Kinzelbach (2008)

- yellowish back and flanks: I would be inclined to interpret this colour as shading rather than as the colour of the feathers.

- peacocks: would probably have been a very familiar bird in the courtyards of Italy in the 13th century, having been traded along the Silk Road for centuries before. Like the cockatoo, those drawings would have been based on live speciemens

- likely species: Dalton et al. (2018) do seem to favour the Yellow-crested Cockatoo in their analysis, so it is curious to me that they make such a fuss about the trade routes, since the range of the Yellow-crested on one of those mediaeval routes

IMAGES: Cockatoos and peacocks from De Arte copied from the online versions; Frederick II and Silk Road map from Wikipedia; Cockatoos and range map from Handbook of Birds of the World (Rowley 2018); page from Wood and Fyfe scanned from the author’s copy.

Heat! Now that’s a good one. Amazing how often in our lives we find an ‘external source of blame’ for any -or all- of our blunders. In the kitchen, on the golf course ( my clubs, the wind, etc) or our laptop! (Hitting delete when it knows you meant send)

But I did enjoy the cacatoo story.

Cheers,

Alan

Without such self delusion, we would probably go mad!

Dear Bob,

have read your intersting article about the cockatoo. I did not have this bird on my radar, but had a quick look in the work by Ragnar Kinzelbach „Von der Kunst mit Vögel zu jagen“. He has already quite acuratly discussed this topic not so elaboratly (on two pages) but in any case gives also further refernce to early occurances in Europe. So this is maybe not really all that knew to ornithology but in any case gave good publicity to the history of ornithology.

Kind regards

Josef Feldner