By Ronald L. Mumme and Claire Lignac

Linked paper: Brood parasitism of Hooded Warblers by Brown-headed Cowbirds: Severe impact on individual nests but modest consequences for seasonal fecundity and conservation by Claire Lignac and Ronald L. Mumme, Ornithological Applications.

Even the most ardent bird enthusiasts find it tough to love the Brown-headed Cowbird. An obligate brood parasite that is widespread in North America, the Brown-headed Cowbird lays its eggs in the nests of more than 240 different host species, an act that has multiple negative and sometimes devastating consequences for host nest success. For example, female cowbirds regularly remove or damage host eggs, reducing the number of viable eggs in the complete clutch and increasing the risk of nest abandonment. Furthermore, because cowbird eggs develop rapidly and usually hatch sooner than host eggs, cowbird nestlings gain a developmental head start and competitive advantage that can impair growth and survival of host nestlings. Finally, the noisy begging calls of cowbird nestlings may attract predators and increase nest predation. The cumulative impact of cowbird parasitism on host nest success can therefore be substantial, and there has been long-standing concern that cowbird parasitism may be contributing to major ongoing population declines of North American songbirds.

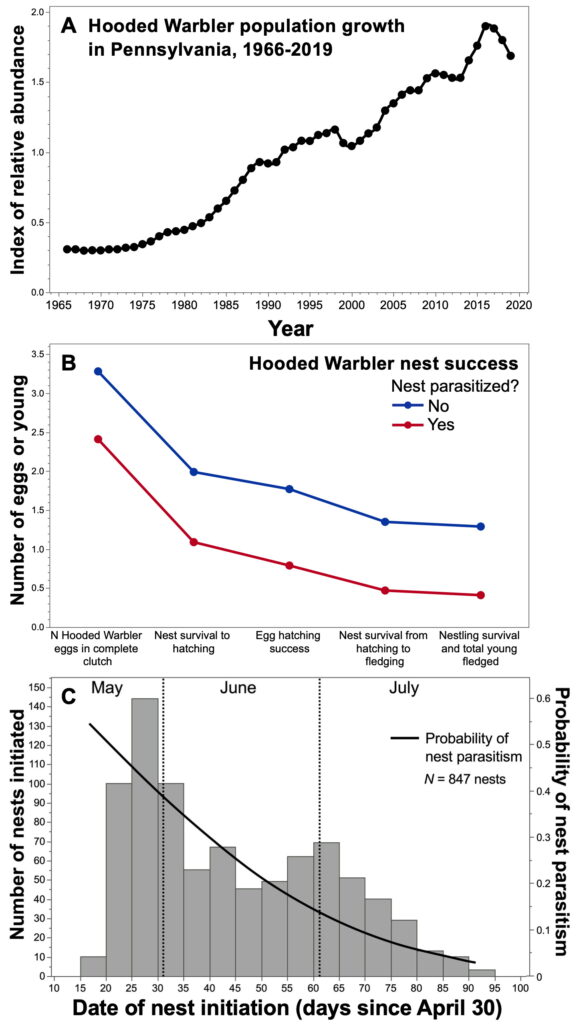

But one common cowbird host, the Hooded Warbler (Figure 1), has somehow shown significant long-term population growth (Figure 2A) despite frequent nest parasitism. How has it done it? We addressed this question as part of our ongoing study of Hooded Warblers at Hemlock Hill Field Station in northwestern Pennsylvania. Our analysis is based on both an extensive dataset (8 years 847 nests) on the per-nest impacts of cowbird parasitism, and stochastic computer simulations that accurately reflect the breeding biology of Hooded Warblers and Brown-headed Cowbirds at our study site.

Hooded Warblers at Hemlock Hill are highly vulnerable to cowbird parasitism, with a nest parasitism rate of nearly 50% for early-season nests initiated in May and early June. As is true for most small-bodied hosts, cowbird parasitism has numerous detrimental consequences for Hooded Warblers, including a reduced number of host eggs in the complete clutch, increased nest abandonment, higher rates of nest predation, and increased egg loss, hatching failure, and nestling mortality in surviving nests (Figure 2B). We estimate that parasitism reduces the success of Hooded Warbler nests 68%, from a mean of 1.29 to 0.41 fledglings per nest.

At the population level, however, our simulations show that the consequences of nest parasitism are considerably less extreme, with mean Hooded Warbler female fecundity decreasing just 5.6% for each 10% increase in the frequency of nest parasitism. This more modest population-level impact is largely attributable to the timing of breeding for the two species at our study site. Hooded Warblers at Hemlock Hill regularly double-brood and initiate nests from mid-May through the end of July, with a second peak of nesting in late June and early July (Figure 2C). Cowbird parasitism, in contrast, declines precipitously as the season progresses, from a high of around 50% for nests initiated in May to nearly 0% for nests initiated in mid-July (Figure 2C). In addition, when early nesting attempts fail, female Hooded Warblers renest rapidly, with the first egg of a replacement nest typically laid 6 days after failure of the previous attempt. Consequently, many Hooded Warbler nests are initiated later in the season when rates of cowbird parasitism are lower. Our findings show how warblers and other small-bodied cowbird hosts, species that typically pay severe per-nest costs for brood parasitism, can not only sustain moderately high rates of nest parasitism but actually thrive and show long-term population gains.

Despite our finding that the population-level effects of cowbird parasitism are relatively modest, we confess that we still dislike Brown-headed Cowbirds. Searching for and finding Hooded Warbler nests is one of the most enjoyable and rewarding aspects of field work on this species; however, the joy and gratification of finding a nest is always dampened when we peer inside and discover that it contains a cowbird egg, as the nest’s potential for contributing to the next generation of Hooded Warblers is now severely diminished. Nonetheless, we cannot help but have a sense of admiration that a female cowbird—without our years of education, training and experience, and with a brain the size of a pea—had already found a nest we may have spent hours searching for. We may not love Brown-headed Cowbirds, but they have earned our respect!

Well done! Detailed review of a wonderfully complex interaction of species with different, but related, reproductive strategies.

Super!

Thanks, Alan!

Thank you for the fascinating discovery you did at my farm in PA! I personally witnessed a pair of house finches laboriously build a nest with 3 eggs and i saw 1 large brown egg in it outside my living room window on my porch. it was sad for me to check it everyday then and only see one very large cowbird baby in it they were feeding… i guess it can get very personal to see this happen….but of course the science will give us answers as to what we should or should not do.

Thanks, Alan!

Thanks Heather! Yes, I know well the personal and conflicted feelings about cowbirds. I hope to see you at Hemlock Hill sometime!