In his Ornithological Biography [1], John James Audubon describes two experiments that have become legends in the annals of ornithology. Both were ingenious ideas, but Audubon’s conclusions were misleading and remained uncorrected for more than a century. According to a new paper by Matthew Halley in Archives of Natural History, one of those experiments might never have been conducted at all.

In the spring of 1804, just before his 19th birthday [2], Audubon found an Eastern Phoebe nest in a cave near where he was living, at the plantation his father had purchased at Mill Grove, Pennsylvania [3]. Audubon had arrived from France a few months earlier and immediately began exploring the countryside where, he said “Hunting, fishing, drawing, and music occupied my every moment; cares I knew not, and cared naught about them. I purchased excellent and beautiful horses, visited all such neighbors as I found congenial spirits, and was as happy as happy could be.” [4]

Audubon wondered whether his phoebes might exhibit what we would now call ‘natal philopatry’: “I had at that period an idea that the whole of these birds were descended from the same stock.” [5]. To test that idea, he put some ‘light threads’ on the legs of the 5 nestlings. The birds, or their parents, repeatedly removed those threads but finally gave up [6]. Once the birds had habituated to the threads, Audubon says that “when they were about to leave the nest, I fixed a light silver thread to the leg of each, loose enough not to hurt the part, but so fastened that no exertions of theirs could remove it.” [7]. Others have, I think, misinterpreted Audubon’s ‘silver thread’ as being silver-coloured yarn but the term is (and was) also used for wire made of silver. Audubon later refers to these as ‘rings’ (see below) suggesting that they were solid and unlikely to be removable by the birds.

The next year, Audubon claims, he found two of those marked phoebes—which he called pewees—nesting near where they were born:

…I had ample proof afterwards that the brood of young Pewees, raised in the cave, returned the following spring, and established themselves farther up on the creek…At the season when the Pewee returns to Pennsylvania, I had the satisfaction to observe those of the cave in and about it. There again, in the very same nest, two broods were raised. I found several Pewees nests at some distance up the creek, particularly under a bridge, and several others in the adjoining meadows, attached to the inner part of sheds erected for the protection of hay and grain. Having caught several of these birds on the nest, I had the pleasure of finding that two of them had the little ring on the leg.” [8]

Now Halley—correctly I think—calls into question the veracity of these observations of natal philopatry, First, he points out, the 40% return rate (2 of 5 banded) of Audubon’s nestling phoebes far exceeds the rate of natal philopatry for this species—and indeed all passerine birds [9]—revealed in subsequent research with large sample sizes. Work done from 1988-90 at my own institution’s field station by Kelvin Conrad, for example, showed a 1.3% return rate of 217 banded nestlings [10]. A much larger study in Indiana [11] found that only 218 of 11,847 (1.8%) phoebe nestlings returned to anywhere within a 250-km2 study area. Based on those numbers, the chance that 2 of Audubon’s 5 nestlings actually returned is almost zero.

Second, Halley checked the dates of Audubon’s return to France (12 March 1805) and subsequent arrival back in Mill Grove (4 June 1806). Based on the normal first egg dates from nearby sites, Halley argues that Audubon could not have been at Mill Grove during the 1805 breeding season and could therefore not have observed the returns he claimed. While I think Halley is correct, it is always possible that Audubon was mistaken about the years when he conducted this experiment.

My guess, though, is that Audubon did actually make up this story, not about banding the birds [12] but about them returning to their natal site. Audubon was well known to be desperate to establish his reputation as an ornithologist, in part, at least, to enhance the sales of his fabulous collection of etchings based on his paintings of North American birds. Audubon was often at odds with Alexander Wilson and George Ord, sometimes plagiarizing Wilson and fabricating evidence so that he would be seen as the first to record a species of bird or an interesting observation [13]. Elliott Coues, for example, said that Audubon: “..loved warmth, color, action; he liked to exaggerate and ’embroider,’ and make his page glow like a hummingbird’s throat, or like on of his many marvellous pictures; he had no genius for accuracy, no taste for dull, dry detail, no care for a specimen after he had drawn it.” [14]

Audubon’s other misleading experiment was designed to assess the ability of Black Vultures to detect odours, but that is a story for another day. Whether or not Audubon was always accurate in his descriptions of bird behaviour or his timelines of events, his experiments were certainly ingenious. He probably does deserve credit as the first person to band birds in North America, and he really could paint a marvellous picture:

SOURCES

-

Audubon JJ (1831-1839) Ornithological biography : or an account of the habits of the birds of the United States of America; accompanied by descriptions of the objects represented in the work entitled The Birds of America, and interspersed with delineations of American scenery and manners. 5 volumes. Edinburgh: Adam & Charles Black

-

Audubon JJ (1827-1838) The Birds of America. Edinburgh & London: J. J. Audubon.

-

Audubon MR (1897) Audubon and His Journals, with Zoological and Other Notes by Elliott Coues, vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

-

Burns FL (1908) Alexander Wilson: II. The Mystery of the Small-Headed Flycatcher. The Wilson Bulletin 20:63–79.

-

Halley MR (2018) Audubon’s famous banding experiment: fact or fiction. Archives of natural history 45:118–121.

-

Weatherhead PJ, Forbes MRL (1994) Natal philopatry and the cost of dispersal in Passerine birds. Behavioural Ecology 5:426–433.

- Weeks Jr HP (2011) Eastern Phoebe (Sayornis phoebe), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Footnotes

- Ornithological Biography: designed by Audubon, with the help of William MacGillivray, to accompany his paintings in Birds of North America. This 5-volume treatise (available here) contains many interesting details and insights about birds but is not an easy read.

- 19th birthday: Audubon was born on 26 April 1785 in the French colony that is now Haiti

- Audubon’s home: Audubon travelled from France to Mill Grove by himself, on the orders of his father to manage the plantation but was more interested in natural history and he eventually drove the plantation into bankruptcy

- quotation about hunting etc: from Audubon 1897, page ; one of the neighbours he talks about was William Blakewell, father of the woman he married a couple of years later

- quotation about phoebe philopatry: from Audubon (1831-39) vol 2, 1834, page 125

- phoebes removing threads: this thread removal and habituation must have occurred over less than two weeks as phoebes leave the nest after 16-18 days

- quotation about silver threads: from Audubon (1831-39) vol 2, 1834, page 125

- quotation about returning phoebes: from Audubon (1831-39) vol 2, 1834, page 125-127

- natal philopatry of passerines: Weatherhead and Forbes (1994) summarized the rates of natal philopatry for 32 migratory passerines from various published and unpublished studies. The highest recorded rate of natal philopatry was 13.5%, and the majority of species had rates <5%, much lower than Audubon recorded for his phoebes

- natal philopatry in Ontario: unpublished data summarized in Weatherhead and Forbes (1994)

- natal philopatry in Indiana: unpublished data summarized in Weeks (2011)

- Audubon banding birds: I am inclined to believe that Audubon did band those birds as the details ring true. He thus deserves his reputation as America’s first bander, preceding by almost a century the next attempt to band birds in the America’s

- Audubon’s conflicts and plagiarism: see Halley (2018) for a brief summary

- Elliott Coues quotation: as quoted by Burns 1908 page 68

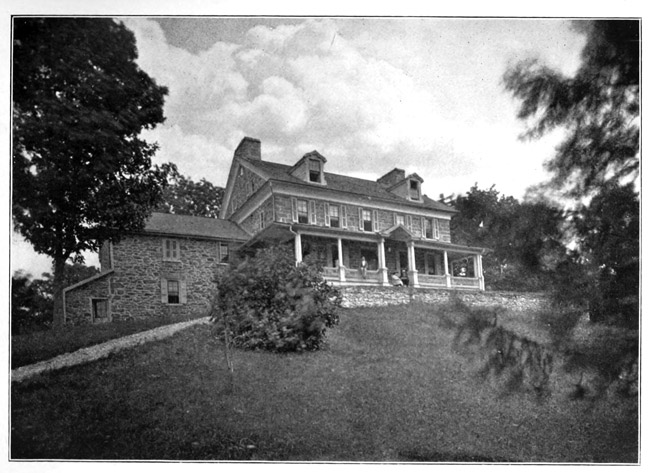

IMAGES: Audubon mansion from Audubon (1897); Audubon’s paintings from his Birds of America (1827-38)