The year I turned 21, I got my dream job: seasonal naturalist at Algonquin Provincial Park. Algonquin, established in 1893, was only the second provincial park to be created in Canada, and the first to be designated to protect a natural environment [1]. This vast ‘wilderness’ area (7653 km2) is only 3 hours by car from Ottawa, 4 from Toronto, and 5 from Montreal. The park now gets more than a million visitors a year, concentrated mainly along the highway that runs east-west across its southern edge. At the time, I had birded and bird-banded only in southwestern Ontario, so this was a chance to see some boreal species on their breeding grounds, species that I had only seen previously on migration or in winter, if at all—Common Loons, White-throated Sparrows, Saw-whet Owls, Pine Grosbeaks, Red Crossbills, Ravens, Three-toed Woodpeckers, and Gray Canada Jays.

Because I was no longer in school, I started work at Algonquin two months earlier than the other half dozen seasonal naturalists, mainly to get the museum’s [2] specimen collections in order and to prepare for the onslaught of summer visitors. Seasonal naturalists were hired to interact with the visitors who flooded the park in July and August during the public schools’ summer vacation. I arrived at Algonquin at the end of April where I met Russell J. Rutter, the only full-time park naturalist, who lived near the small town of Huntsville, a half hour west of the park. Rutter was a crusty old guy but we got on well and he often took me out birding, botanizing, hiking the trails where we would lead nature walks, and howling for wolves [3].

One day, as we walked along some abandoned railway tracks, 3 Canada Jays appeared at the edge of the woods. Russ made a whispery-squeaky sound and all three birds flew right up to us, one landing on Russ’s hand to get some food that he had brought with him just for that purpose. Two of those jays had colour-bands (WR, and YORL [4]), and this was a family group, Russ said. Russ told me he had decided a few years earlier to start studying Canada Jays so that he could follow individuals through their lives. He had already discovered that they often travel in family groups, hoard food for the winter, and occupy year-round territories. I was enthralled—I had no idea that the birds I had watched breeding in southern Ontario were not doing what all birds did.

Russ was also furious with the AOU for changing the bird’s common name from Canada Jay to Gray Jay in its 1957 checklist. I must admit I was not really even aware of this as my field guide—the 3rd edition of Peterson, published in 1947—called them Canada Jays and that’s what I would have called them but I had never seen one before. That summer, we naturalists often told the park visitors about the name change but also that the Native Algonquins had once called them whisky-jacks, which made for a good story.

One of the seasonal naturalists that year was Dan Strickland, who had been an Algonquin Park naturalist the previous summer or two and was now studying Canada Jays (‘Geais Gris’) for his MSc thesis at the Université de Montréal. Dan was conducting his research in la réserve faunique de La Vérendrye in Québec, inspired by Rutter’s work in Algonquin. Dan’s focus was on their social behaviours and their food-caching strategies. He stayed at Algonquin as Park Naturalist for the rest of his career, and has continued to work on the Canada Jay for the past half century, one of the longest continuous studies of a bird species worldwide. Not surprisingly, Strickland was instrumental in the recent official change of the species’ name back to Canada Jay just last month. The popular press in Canada is all abuzz about this change, in part because calling them ‘Canada Jays’ may enhance the possibility that this species will now be recognized as Canada’s national bird.

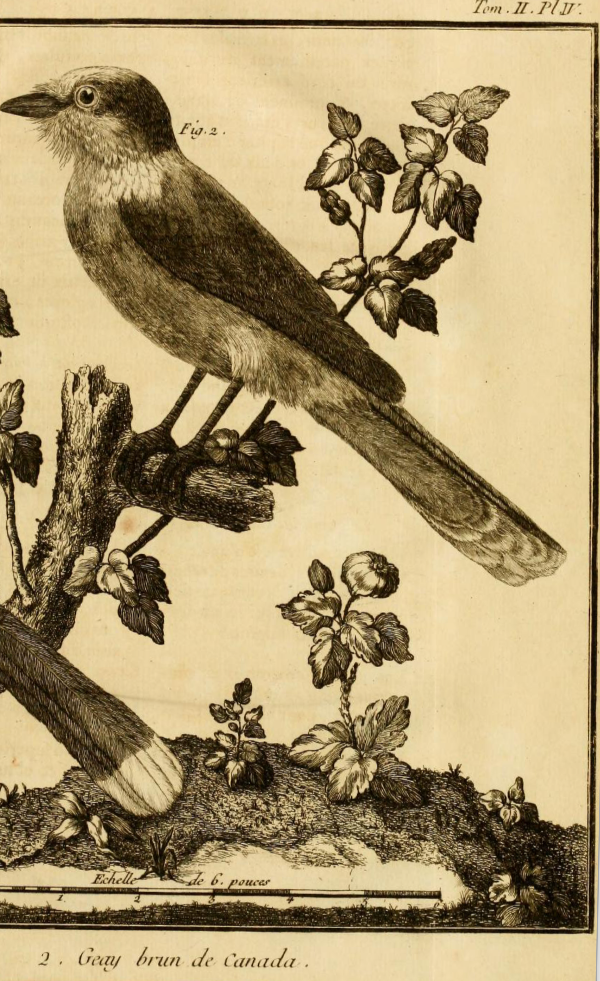

The Canada Jay was first described for science in 1760 as ‘Le Geay brun de Canada’ (Garrulus Canadensis fuscus) by the French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson in his Ornthologie, with a remarkably good illustration by François Nicolas Martinet. An English translation of Brisson’s common name might be the ‘Canada Brown Jay’ [5]. This description, and the illustration, were based on a specimen in the collection of René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur, as neither Brisson nor Martinet had seen the bird in the wild. de Réaumur was primarily an entomologist but he had an extensive private museum where he employed Brisson as what we would today call a ‘curator’. Brisson’s description was the basis for Linnaeus presenting the bird’s ‘official’ scientific name as Corvus canadensis, in 1766, but Linnaeus did not suggest a common name, as that was not the purpose of his work.

Thomas Pennant was probably the first to publish an English common name—Cinereous Crow [6]— for this species, in his Arctic Zoology of 1784. Pennant had never seen the bird alive either, relying instead on Samuel Hearne’s description [7]. Hearne joined the British Navy at the age of 11 and then the Hudson’s Bay Company at 21, stationed first at Fort Prince of Wales (now Churchill) in Manitoba. While there, he made 3 major expeditions into the interior of present-day Nunavut, in 1771 reaching the mouth of the Coppermine River where it drains into the Arctic Ocean. Hearne’s Journey, published posthumously in 1795, contains detailed species accounts of at least 50 bird species that he encountered on his expeditions, with remarkable insights into their behaviours and ecologies. Hearne called this jay the ‘Cinereous Crow (Perisoreus canadensis)’, noting in his account that “..it is called by the Southern Indians [presumably Cree], Whisk-e-jonish, by the English Whiskey-Jack, and by the Northern Indians [presumably Chipewyan] Gee-za…” [8]

Then, in 1829, John Richardson called this bird ‘The Whiskey-Jack (Garrulus canadensis)’ in his comprehensive Fauna Boreali-Americana, coauthored with William Swainson. Richardson had explored northern Canada with the Franklin Expeditions of 1819-22 and 1825-27, and would have had first hand experience with this species. A half-century later, with the publication of the first AOU checklist in 1886, the official names became Canada Jay and Perisoreus canadensis, and would remain that way until 1957.

During the Washington AOU conference in 2016, Dan Strickland mined the AOU archives at the Smithsonian to figure out how and why the common name of this species was changed by the AOU in 1957. Based on that information, he made a very compelling case to have the name changed back to Canada Jay. The details are complex but nicely outlined by Strickland here and here.

While the scientific names of birds (and all plants and animals) are assigned following some strict rules, there are no such rules for common names. Attempts to make some rules for common names have not been successful (see here for example), and for good reason, I think. Common names say something—not always useful (see here)—about appearance, vocalizations, habitat, and localities, as well honouring people—not always logically (see here)—and their contributions to science or discovery. Common names are what most of us use when we talk about birds and ‘official’ common names should probably, like all language, reflect usage rather than some esoteric rules. No amount of rule-making will stop duck hunters from using the names ‘whistler’, ‘sprig’, ‘greenhead’, ‘bluebill’, spoonbill’ or ‘skunkhead coot’ [9], nor the visitors to Algonquin Park from calling their favourite bird the ‘whiskey-jack’.

SOURCES

- American Ornithologists’ Union (1886) The code of nomenclature and check-list of North American birds. New York: American Ornithologists’ Union.

- American Ornithologists’ Union (1957) Check-list of North American birds. Ithaca, N.Y.: American Ornithologists’ Union.

- Brisson M-J, Martinet FN (1760) Ornithologie, ou, Méthode contenant la division des oiseaux en ordres, sections, genres, especes & leurs variétés (t.2 ). Parisiis: Ad Ripam Augustinorum, apud Cl. Joannem-Baptistam Bauche, bibliopolam, ad Insigne S. Genovesae, & S. Joannis in Deserto.

- Hearne S (1795) A journey from Prince of Wales’s Fort in Hudson’s Bay to the Northern Ocean. London: Strahan and Cadell.

- Houston CS, Ball T, Houston M (2003) Eighteenth-century Naturalists of Hudson Bay. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Linné CV (1766) Caroli a Linné. Systema naturae : per regna tria natura, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis / (t.1, pt. 1 (Regnum animale)), 12th edition. Holmiae :Impensis direct. Laurentii Salvii.

- Pennant T (1784-85) Arctic Zoology, 2 vols. London: Henry Hughs

- Rutter, R.J. 1969. A contribution to the biology of the Gray jay (Perisoreus canadensis). Canadian Field-Naturalist 83: 300-316.

- Strickland D (1969) Écologie, comportement social et nidification du Geai Gris (Perisoreus canadensis). Master’s Thesis, Univ. Montréal, Montréal.

- Strickland D (2017) How the Canada Jay lost its name and why it matters. Ontario Birds 35: 2-16.

- Swainson W, Richardson J (1831) Fauna boreali-americana, or, The zoology of the northern parts of British America: containing descriptions of the objects of natural history collected on the late northern land expeditions, under command of Captain Sir John Franklin, R.N. Part second, the birds. London: John Murray.

Footnotes

- Canadian provincial parks: Queen Victoria Park at Niagara Falls was Canada’ first provincial park, established in 1885 in part to clean up the area around the falls and reduce the incidence of crime

- Algonquin park museum: in those days was on the shore of Found Lake but now is a spectacular Visitor Centre 30 km east of the old museum

- howling for wolves: the Algonquin Wolf Howl, held in August every year, attracts more than a thousand visitors who gather at the roadside at sunset, hoping to hear the wolves respond to the park naturalists’ attempts to imitate the howls. Those howl imitations are so good that one year the naturalists mistakenly called back and forth to each other, each group assuming that they were hearing real wolves.

- colour-bands: the letters refer to the colours, usually left-leg top and bottom, then right-leg top and bottom. So these birds were white on the left, red on the right, and yellow over orange on the left and red over light-blue on the right. Researchers like band combos that they can pronounce so these birds were ‘whir’ and ‘yorel’ to Rutter.

- Canada Brown Jay: in Brisson’s day, ‘Canada’ referred to the French colony that we now call Québec.

- Cinereous Crow: ‘cinereous’ means ‘ashy-grey’ which correctly describes the bird’s colour but we can be grateful that this name was never used after the middle of the 19th century. I have little doubt that early explorers to Canada in the 16th and 17th centuries will have said something about this species but I cannot find an earlier reference than Brisson (1760)

- Samuel Hearne’s description: we know that Hearne gave Pennant a copy of his observations while Hearne was in England during the winter of 1782-83 (Houston et al. 2003)

- quotation about Native names: from Hearne (1795, page 374)

- hunter’s names for ducks: officially (AOU checklist) these are Common Goldeneye, Norther Pintail, Mallard, Lesser (or Greater) Scaup, Northern Shoveler, and Surf Scoter, respectively

IMAGES: Canada Jay photo by the author; pages from AOU checklists and Brisson are in the public domain

COMMENTS