Back in the 1980s, one of my graduate students and I split the cost of an Ontario Lottery ticket. We knew that the chances of winning were vanishingly small (p<0.000001) but the jackpot had risen to $24 million—real money in those days. It was a cheap and fun investment that could really help my research program if we won. We spent the next couple of weeks in the field, often chatting about what we might do with the winnings.

We eventually decided that, if we won, we would buy a nice plot of land in the arctic or the tropics, and build a field station. We figured there would be enough money to allow us to employ and fund a dozen or so field biologists to work at the station—people who would be engaging, creative and productive, with the freedom to explore whatever interested them. We did not win that particular lottery but both of us realized our dream by supervising some outstanding graduate students and postdocs in the intervening 30+ years, and working with them in the field.

In 1899, Edward Harriman was faced with an opportunity like our dream of winning that lottery, but he already had the funds to make it happen. Harriman was what we used to call a railroad tycoon, and was one of the richest and most powerful businessmen in the United States. By 1899, when he was 51, Harriman was director of the Union Pacific Railroad and already fabulously wealthy. He achieved that success through incredibly hard work, combined with a keen mind and outstanding business acumen. The hard work, though, had taken its toll on his health, so, in January 1899, his doctor recommended a long vacation.

For Harriman, though, the idea of lying on a beach, visiting European cathedrals, or golfing for a month or two held little interest. But he knew he had to get away from the day-to-day running of his businesses for a while. His first thought was to spend a few weeks hunting Kodiak bears in Alaska, something he had always wanted to do. As often happens with type ‘A’ personalities, though, that simple ‘idea’ soon blossomed into a gargantuan endeavour involving huge expenses, dozens of people, and complex travel arrangements. Just as we had done 80 years later, Harriman thought it would be incredible to gather together some of the best field scientists in America and take them to an interesting place, all expenses paid and no expense spared.

To assemble a coterie of top scientists—geologists, historians, anthropologists, zoologists and botanists—Harriman, in March 1899, asked his friend C. Hart Merriam at the U.S. Department of Agriculture for help. Merriam was a founding member of the AOU (now AOS), the brother of Florence Merriam Bailey (see post here), and one of the top American zoologists of the day. Within three weeks, Merriam had convinced an incredible array of participants to join the Harriman Expedition, due to depart Seattle at the beginning of June. In addition to Merriam, these included ornithologists Robert Ridgway, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, Charles Keeler, Leon J. Cole, and Albert K. Fisher, as well as 10 other biologists, 5 geologists/geographers, and a dozen artists and photographers among others. The naturalists/authors John Burroughs, John Muir and George Bird Grinnell added to the sterling cast of explorers. Including his family members, a chaplain, taxidermists, cooks and the ship’s crew, a total of 128 people participated in the expedition.

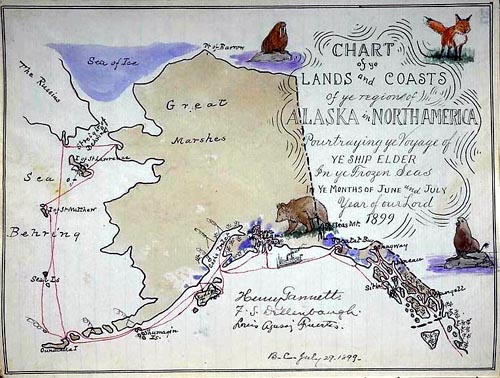

For transportation, Harriman had a steamship, the SS George W. Elder, retrofitted with luxurious staterooms for the members of the expedition, a stable for animals, studios for taxidermists and artists, and even a library of more than 500 books about Alaska. The expedition left Seattle to much fanfare on 31 May, heading north up the coast of British Columbia to Alaska.

Over the next two months they explored the coasts and islands of Alaska as far north as the Bering Strait where they landed on both the Alaskan and Russian shores. Sometimes expedition parties went ashore to camp, hunt, paint, take photographs and collect specimens. Most stops were short as Harriman relentlessly wanted to press on northward. In all, they travelled 14,500 km (9000 miles) by ship, returning to Seattle on 30 July.

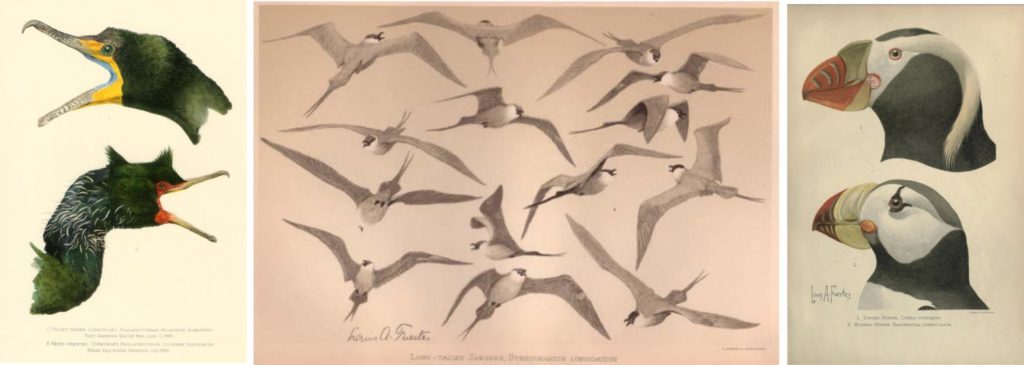

During the course of the expedition, thousands of specimens were collected, a new fjord discovered, 5000 photographs, taken and hundreds of paintings and illustrations produced. Though only 25 years old, Fuertes was already at the peak of his powers as a bird artist and illustrator.

On return Harriman funded the production of 14 volumes of scientific observations, well-illustrated with photographs, drawings and colour plates of paintings. The section on birds was written by Charles Keeler and is largely a narrative of what they saw at different stopping points. Though the expedition did not produce anything very interesting from an ornithological perspective, it was not bad, as Harriman himself said: “as a summer cruise for the pleasure and recreation of my family and a few friends”.

SOURCES

- Burroughs J, Muir J, Grinnell GB (1901). Alaska; Narrative, glaciers, natives; Volume I. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company

- Keeler C (1902) Days among Alaska birds,. pp 205 – 234 IN Dall W, Keeler C, Fernow BE, Gannett H, Brewer WH, Merriam CH, Grinnell GB, Washburn ML. History, geography, resources. Harriman Alaska Series, Volume 2. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company

- various authors (1901- ) Harriman Alaska Series, Volumes 1-14. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company

- websites: Biodiversity Heritage Library, Wikipedia, PBS, Cornell University, Smithsonian