As you might suspect, I find the history of ornithology in particular—and the history of science in general—pretty interesting. But even I am not sure why.

In high school, history was my least favourite subject, taught by Dr A. S. H. Hill—our only teacher with a PhD (and in Political Science)—who insisted on having us memorize long strings of dates and events, aided by a rather pedantic textbook called The Modern Era.

In high school, history was my least favourite subject, taught by Dr A. S. H. Hill—our only teacher with a PhD (and in Political Science)—who insisted on having us memorize long strings of dates and events, aided by a rather pedantic textbook called The Modern Era.

Then in my final undergraduate year at the University of Guelph, the Philosophy Department hired a recent PhD graduate from the University of Bristol named Michael Ruse. Ruse’s first course was called something like Philosophical Foundations of the History of Science. I had taken a few philosophy courses so this one sounded right up my alley. In 1970, Ruse was a mild-mannered, genial new professor but lacked teaching experience. Since he had just completed his degree he decided to devote the whole course to the subject of his thesis research—Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species. Only 6 of us took that class, reading and discussing each chapter in Morse Peckham’s Variorum Text, following the changes that Darwin made as he revised the first 5 editions [1]. I think the other students were bored beyond belief but I was enthralled with this intimate look into the writings of the great man (Darwin), and the insights provided by Ruse.

The demands of (largely) ornithological research kept my nascent interest in history on hold for the next 30 years. Then, largely through discussions with Tim Birkhead, that interest was rekindled at the end of the the last century, and this blog and website are one result. If the proliferation of both books and publications are any indication, I am not the only person who has taken an interest in the history of ornithology of late, with a new book on the topic appearing every few months [2].

In 1984, when The Auk had just published its 100th volume, the editor—John A. Wiens—started a series that he called 100 Years Ago in The Auk because, as he said:

Reading the writings of a century ago reveals a good deal about how our current thinking was anticipated, how far we have come, how little has changed, how ornithologists approached the study of birds then, and the like. Accordingly, this and each following issue of The Auk will contain a selected excerpt from the counterpart issue of a century ago. [3]

As Wiens promised, an excerpt from a paper that had appeared in The Auk 100 years earlier was published in most issues of the journal for the next 15 years, chosen, presumably, by successive editors Alan Brush (1985-90), Gary Schnell (1991-96) and Tom Martin (1997-99). There were none published in 2000 when The Auk had an interim editor. But when Kimberly Smith took over as Editor in Chief in 2001 he saw an opportunity to start a new series that he called 100 Years Ago in the American Ornithologists’ Union. Kim has written these excellent pieces in every issue since January 2001. He did not add his byline until 2005 at the insistence of the new editor, Spencer Sealy, who wanted Kim to get full credit for his work.

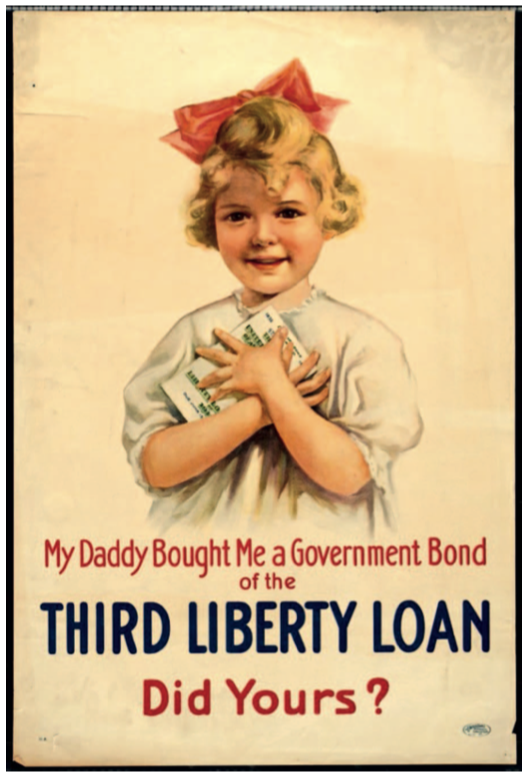

While the extracts from century old papers were interesting and useful in the late 20th century, the ready availability of old issues of The Auk (and other journals) on SORA, would make the series that Wiens began less useful today. Kim Smith’s essays, on the other hand, provide unique insights into AOU conferences, initiatives and publications, often described in the context of contemporary life and science. In his latest piece (Jan 2018), for example, Kim tells how the AOU obtained money through the Liberty Bond Program in the USA to help society members who were serving the WWI.

While the extracts from century old papers were interesting and useful in the late 20th century, the ready availability of old issues of The Auk (and other journals) on SORA, would make the series that Wiens began less useful today. Kim Smith’s essays, on the other hand, provide unique insights into AOU conferences, initiatives and publications, often described in the context of contemporary life and science. In his latest piece (Jan 2018), for example, Kim tells how the AOU obtained money through the Liberty Bond Program in the USA to help society members who were serving the WWI.

In his 1984 essay inaugurating the series of excerpts from a century ago, Wiens said that:

Ornithology was a different sort of discipline then, with much that we now accept as common knowledge yet to be discovered. In some respects, however, ornithologists of a century ago had as much understanding of natural phenomena as we do today, although they expressed themselves using more eloquent prose, less jargon, and far less quantitative detail. [3]

There is some truth in what he says but our ornithological predecessors were often difficult to understand, prone to using anthropomorphisms and the jargon of the day. They were also very quantitative at times but less inclined to use statistical analyses as most of the methods we use readily (and often incorrectly) today had not yet been invented, as Ted Anderson mentioned in last week’s post.

SOURCES

- Peckham M, ed. (1959) The Origin of Species: a Variorum Text. Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press.

- Wiens JA (1984) 100 Years Ago in The Auk. Auk 101:203

Footnotes

- Variorum Text: see Peckham (1959); for a modern online version see here

- New books on history of ornithology: I will be reviewing 3 of these here in the next couple of months

- Quotations: both from Wiens (1984)

Nice post, but discouraging to see the Auk has apparently on male editors during the time you cover. I feel like there are few things I can read these days on any topic that don’t force on me the low status of women.

The editorship of The Auk has traditionally been a volunteer position and the editor is chosen from a list of people who volunteer. I am not sure if any women have volunteered in the past but I will look into it. Right now The Auk is seeking a new editor-in-chief to replace Mark Hauber, who is stepping down. I will do a post on the long history of male editors (and the process of choosing them) after the upcoming meeting where I will try to get more information.

Nice post but discouraging to see yet again a journal, the Auk, with only boyz as editors in your list. I cannot go through even one reading morning without sexism hitting me on the head.