In the fall of 1973, shortly after starting my PhD at McGill University, I decided that I wanted to study a community of hummingbirds in western Mexico. During his own PhD research, my supervisor (major professor), Peter Grant, had discovered an apparent case of character displacement in the bill lengths of two hummingbird species on the Islas Tres Marìas, about 50 km off the Pacific coast at San Blas, Nayarit. Hummingbirds seemed a good choice—both then and now—for a field study as they were abundant, fairly easy to watch, and could be attracted to feeders. Most important for my study, it seemed at least possible to quantify the energetic costs and benefits of their foraging activities and how bill size might influence those costs and benefits.

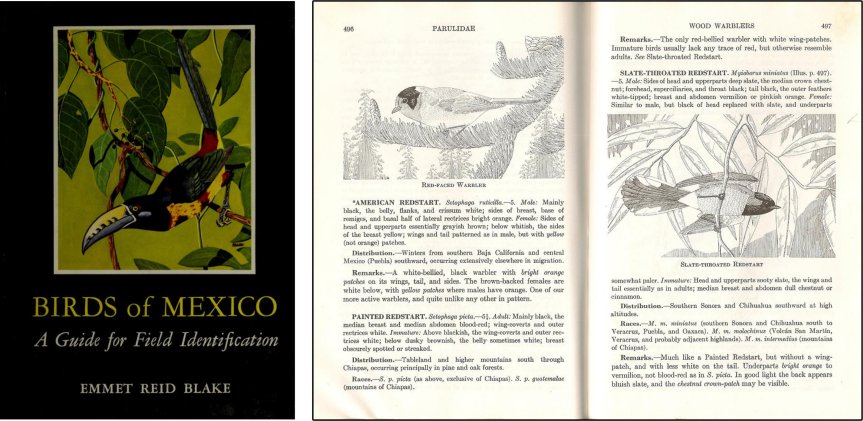

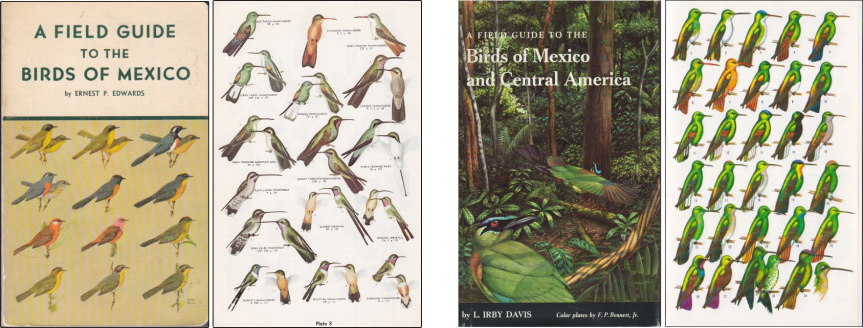

My initial excitement about this project was seriously dampened when I discovered that what I thought was the only field guide to Mexican birds was the one that Peter had used during his field work in the mid-1960s [1]— Emmet Reid Blake’s Birds of Mexico, first published in 1952. Blake’s guide included some drawings but nothing really as useful as the field guides to North American birds that I was so familiar with. Asking around [2], I learned that two new guides to Mexican birds had been published in 1972—Irby Davis’s Field Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Central America and Ernest P. Edwards’s A Field Guide to the Birds of Mexico —both with colour plates.

I ordered them both but when they arrived I saw that field identification was still going to be tough. One of my focal species—Cinnamon Hummingbird—was distinctive and easy, but the other was the Broad-billed hummingbird which looked to me very similar to a half dozen other species that I expected to encounter. From today’s perspective that now feels like I was being overly cautious but at the time I had only ever seen the Ruby-throated hummingbird and the vast array of tropical species made their identification seem bewildering complex. I learned to watch birds with Peterson’s Eastern Guide and Robbins’s Golden Guide in hand so even those new Mexican guides seemed primitive in comparison.

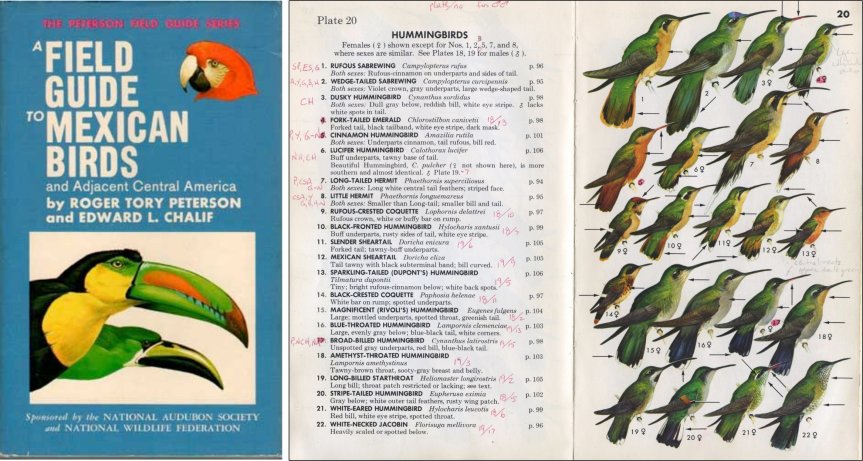

By early October, I had pretty much decided to study gulls in Newfoundland for my PhD when I had one of those life-defining coincidences. My fellow graduate students and I drove from Montreal to Cape Cod to attend the AOU meeting in Provincetown. I told various people about my research dilemma and most commiserated with the problems of field identification in the tropics. Then, in a break between talks, I went to the vendors’ tables and there was the latest Peterson Field Guide—Peterson and Chalif’s A Field Guide to Mexican Birds. The book had actually been published in January 1973 but there was no internet in those days and we usually only found out about new books when the publisher sent around flyers, or we heard by word of mouth.

The new Peterson Guide was perfect for me as it put field identification in terms that I was familiar with—great illustrations, arrows indicating key field marks on every bird [3], and brief, clear descriptions. A quick look at the relevant plates told me that I would have no trouble identifying all the hummingbirds I was likely to encounter in western Mexico. The following June (1974), my colleague Neil Brown and I drove from Montreal to San Blas in June 1974 to begin our PhD research—he studying Thryothorus wren songs in the nearby highlands at Tepic, and I working on the foraging ecology of hummingbirds along the coast. With the Peterson guide in hand, we made a discovery on our way south through Sinaloa that showed how a previous study of Neil’s wrens had probably misidentified them, possibly because those wrens had been too hard to positively identify in the field.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that field guides made bird-watching popular, and continue to attract people to the hobby and to professional ornithology. The very first real field guide—small enough to carry, with details on rapid identification—was probably Florence Augusta Merriam‘s Birds Through an Opera-Glass, published in 1889 by The Chautauqua Press [4]. Florence was encouraged by her parents and her aunt to study natural history and both she and her brother (C. Hart Merriam) became prominent ornithologists.

While attending Smith College (1882-1886), Florence began to write articles on bird protection for Audubon Magazine, and founded the Smith College Audubon Society. She was very interested in studying live birds rather than collecting them for museums. As a result, she one of the first people to suggest watching birds through binoculars to study their behaviour, rather than shooting them: “When going to watch birds, provided with opera-glass and note-book, and dressed in inconspicuous colors, proceed to some good birdy place, — the bushy bank of a stream or an old juniper pasture, — and sit down in the undergrowth or against a concealing tree-trunk, with your back to the sun, to look and listen in silence.” [5}

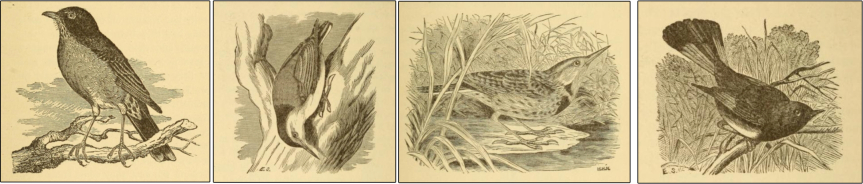

Florence’s guide covered 70 species of land birds common to eastern North America, with a few species illustrated with woodcuts from Baird, Brewster and Ridgway’s History of North American Birds published in 1874. It seems to me that she intended her book to be a guide to bird-watching rather than a guide to identification to be used in the field: “Carry a pocket note-book, and above all, take an opera or field glass with you…watching them closely, comparing them carefully, and writing down, while in the field, all the characteristics of every new bird seen” [6]. That sounds like she is advocating taking notes so that species can be figured out back home, with her book in hand. It would be interesting to know if anyone actually used this book as a field guide back in the day. Some parts of her book would have been useful to the novice trying to identify birds that they encountered—like the drawings and some of the descriptions—but the focus is more on methods and the details of her encounters with each species.

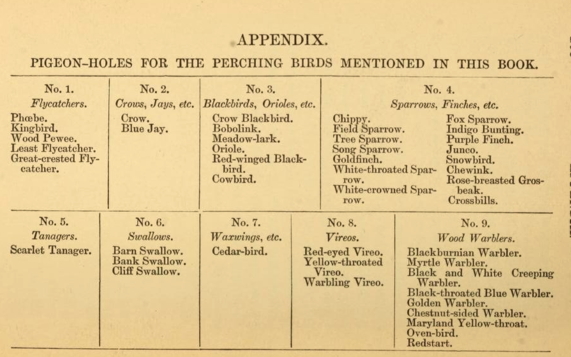

She begins, for example, with a short chapter on how to watch birds and figure out which species is which. She suggests using the abundant and familiar American Robin as point of departure for size, colour, songs, habitats and habits: “Begin with the commonest birds, and train your ears and eyes by pigeon-holing every bird you see and every song you hear. Classify roughly at first, — the finer distinctions will easily be made later” [7] She adds three Appendices with suggestions on pigeon-holing species to facilitate identification, on general family characteristics, and on classifying birds with respect 10 different traits that could be observed in the field.

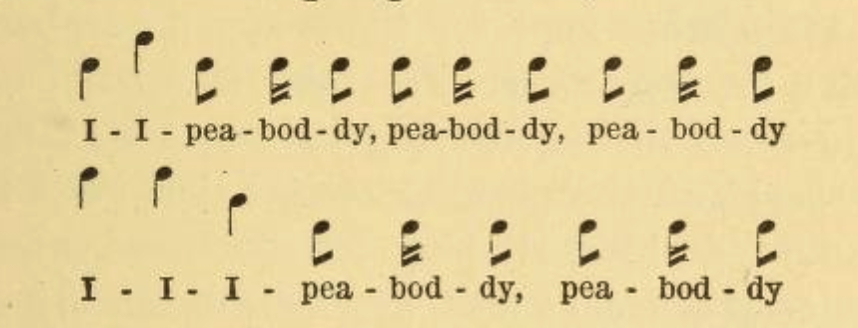

Most of Merriam’s book is devoted to those 70 species’ accounts, starting with the American Robin. These are charming, interesting and detailed descriptions of the birds and their habits, based largely on Florence’s own observations in the field. These must be among the first published details of the behaviour and ecology of most of these species, anticipating the sort of life histories that Arthur Cleveland Bent would begin publishing 30 years later. In some cases—like the thrushes—she presents information to allow the observer to distinguish similar species, and for many she includes details of song including notes and mnemonics, as shown below.

We have come through a half dozen revolutions in field guides since Merriam’s day, marked by things like printing all species in colour, Peterson’s field marks method, lifelike paintings showing all plumages, sonograms, and range maps. As I prepare to head off to Alaska for field work next week, I will make sure that my iPhone has the latest Sibley and ebird apps, but I won’t be taking any books. Birders can now go to almost any country in the world with a useful field guide, notebook and camera in their pocket. Florence began her little field guide with “Wherever there are people there are birds…” [8] but now, as a result of the hobby that she promoted, it would be fair to say that wherever there are birds there are people.

SOURCES

- Baird SF, Brewer TM, Ridgway R (1874) A History of North American Birds: Land Birds, Vols 1-3.. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

- Bent AC (1919) Life Histories of North American Diving Birds. U. S. National Museum Bulletin 107.

- Brewster W (“W.B.) (1889) Recent Literature: Birds Through an Opera Glass. The Auk 6: 330

- Brown RN (1979) Structure and evolution of song form in the wrens Thryothorus sinaloa and T. felix. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 5: 111-131

- Grant PR (1965) A systematic study of the terrestrial birds of the Tres Marias Islands, Mexico. Postilla 90:1–106.

- Merriam FA (1890) Birds Through an Opera-Glass. New York: The Chautauqua Press.

Footnotes

- field work in the 1960s: since Grant was collecting birds, a field guide was not particularly important for most of his research.

- asking around about field guides: without email, this was a tedious and slow process of letter writing in those days.

- arrows indicating key field marks: I seem to recall that Peterson patented this method, which is why no other field guides could use it

- Chautauqua Press: the back of the title page says “This edition of “Birds Through an Opera-Glass” is issued for The Chautauqua Press by Houghton, Mifflin & Co., publishers of the work.”

- quotation about bird watching: from Merriam 1889: page iv

- quotation about notebooks: from Merriam 1889: page 3

- quotation about pigeon-holing: from Merriam 1889: page 1

- quotation about people and birds: from Merriam 1889: page 1

As a field guide fan – you could actually say ‘-aholic’ – I love this! Our (South Africa) first field guide to our birds was by Austin Roberts in 1940. It is still going – 7th edition – and numerous others have joined it, my favourite being Newman’s field guide. Of course they’re all going digital now (my fear is the bird sounds in the hands of so many people will cause chaos in the field, but there’s no stopping it – that bird has flown!). We ‘re lucky to have field guides on many of our creatures and plants – even ‘down’ to ‘the snails and slugs of SA’!