In the summers of 1966 and 1967, I worked (Dream Job #2) for Bill Carrick at the Niska Waterfowl Research Station near Guelph, Ontario. Bill was an outstanding wildlife cinematographer and a superb naturalist who was director/manager of that facility. My job was to raise and feed the myriad birds and mammals that he used in his films, and to act as what in film lingo is called ‘best boy’, looking after equipment and lighting, as well as nest-finding when we were in the field.

I lived on the property with Bill and his family and every morning took chicken scraps from the local butcher out to the feed several hawks and owls housed in big flight aviaries at the edge of a woodlot. The raptors largely ignored me as I cleaned up leftovers and piled chicken parts on a platform for their daily meal. One day, though, I heard a whoosh behind me and as I turned saw a red-tailed hawk with talons splayed, only a meter from my face. I somehow dodged in panic but one of the bird’s talons ripped open the left side of my head with a gash starting only a cm or two from my eye.

As Bill’s wife, Mary, was patching me up, he told me the story of Eric Hosking, who had lost an eye to a Tawny Owl when he was only 28 but already famous for his bird photography. Hosking lived in north London and in the spring of 1937 had set up a blind on a Tawny Owl nest near his home. Late in the evening of 12 May, he was climbing to his blind when one of the parent owls attacked (as they are now well known to do around their nests), striking his face and blinding his left eye. While this was a tragic accident, the subsequent publicity marked a turning point in Hosking’s career. Although Hosking’s photos were already widely published, the publicity over the loss of his eye while photographing birds made him a national celebrity.

Hosking was a spectacularly good bird photographer, who went on to write at least 14 books illustrated with his photographs. In 1970, he published his autobiography, An Eye for a Bird, in which he described how he lost his left eye more than 30 years earlier. That book was wildly popular and went through at least 7 editions. Just last year, it was made available in digital form on Amazon UK Kindle (here).

Hosking’s best photos, in my opinion, show birds in action, and are not simply portraits of birds on a pond or a stick. His action photos are all the more remarkable because, by today’s digital standards, bird photography in the 1930s was staggeringly difficult. To take a picture in those days, the photographer had to calculate the best f-stop and shutter speed for the lighting conditions, focus on a plate on the back of the camera, insert the film holder (containing a glass plate with the emulsion on one side) into the camera, and then hope nothing changed when the bird showed up and the shutter was pressed. Photographers among you will recognize how difficult it must have been to take pictures at the equivalent of ISO 10. On a good day, Hosking might get 12 exposed plates that he could take home to develop and print.

Like all photographers that I know, Hosking liked to keep on top of the latest technological advances. He was one of the first to use flash bulbs in bird photography, thereby obtaining some of the earliest photos of birds at night. Previously, he would have had to use flash powder that must have been incredibly dangerous in woods and grasslands. In the 1940s, he also pioneered the use of electronic flash to capture and freeze birds in flight, showing things that nobody had been able to see before, like the bending of feathers and the angles of the wings on the up- and down-strokes.

Because of, and in addition to, his contributions to bird photography, Hosking wrote several papers for bird journals, and was a champion for bird conservation. He was also president or vice-president of the BOU, RSPB, the Nature Photographic Society, and the British Naturalists’ Association, and was awarded the Order of the British Empire for his contributions to both nature photography and conservation. In 1965, the Natural History Museum began a Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition that Hosking often judged. The first winner was C. V. R. Dowdeswell for his colour photo of a Tawny Owl [1], presented by none other than David Attenborough [2].

Hosking was not the first bird photographer to gain national and international fame for his work. That honour is shared by Richard and Cherry Kearton in England, and a trio of naturalists in America. The Kearton brothers [3] were from a small village in the Yorkshire Dales where they developed an early interest in photography. Their first bird photos were taken in the 1880s, when they were in still in their teens. Cherry is credited with taking the first photo of a bird’s nest and eggs in 1892, when he was just 21. In 1898, the Keartons published a book (available here), With Nature and a Camera, about their 1896 trip to St Kilda in the Outer Hebrides northwest of Scotland. That book—illustrated with 160 of their photographs—is still quite readable, full of observations of and insights into the relationships between the people and birds on those remote islands, and the techniques developed by the Keartons for observation and photography.

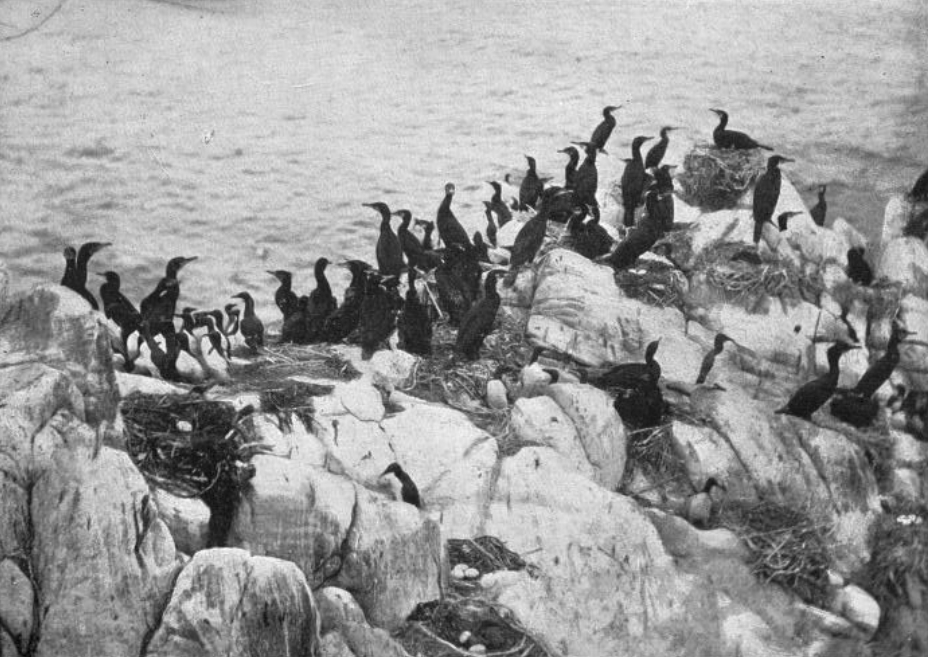

While the Keartons were exploring St Kilda, two American naturalists—William L. Finley and Herman T. Bohlman, both in their twenties—were beginning to photograph birds in the western USA. One of their goals was to use their photography to promote bird conservation. In 1905, Bohlman and Finley explored the Klamath River Valley along the Oregon-California border. Their writings and photos were a major impetus for President Teddy Roosevelt to set aside federal bird refuges in the west.

In 1907, Finley and Bohlman published American Birds (available here), with 21 chapters, each about a different species and illustrated with 137 of their photographs. Finley married his wife, Irene, in 1906, and she accompanied him on all of his subsequent expeditions, gradually taking over from Bohlman who decided to stay at home to attend to his family. All of their archived photographs (available here) are attributed to all three people so it is now impossible to know who took what, but clearly Irene was one of the earliest, and few, women bird photographers

As for bird collecting and egg collecting, bird photography has been largely a man’s game, with precious few exceptions. This 2015 listing of the world’s dozen best bird photographers, for example, mentions no women. I am aware of a few very talented women nature photographers working today and will highlight their work in a later post,. Many of those women, like Irene Findley, often shared the limelight with their male partners, or worked in their shadows

SOURCES

- Bevis J (2007) Direct From Nature: The Photographic Work of Richard & Cherry Kearton. Axminster, UK: Colin Sackett.

- Edwards G, Hosking E, Smith S (1947) Aggressive display of the ringed plover. British Birds 40:12–19.

- Finley WL, Bohlman HT (1907) American Birds: Studied and photographed from life. New York: Scribner’s.

- Hosking D. (2017) Book Review: An Eye for a bird. British Birds (3 Jan 2017 available here)

- Hosking E, Lane F (1970) An Eye for a Bird. London: Hutchinson.

- Kearton R, Kearton C (1898) With nature and a camera; being the adventures and observations of a field naturalist and an animal photographer. London: Cassell.

Footnotes

- colour photo of a Tawny Owl: is it just a coincidence that this was the winning photo, as that was the species that had taken out Hosking’s eye

- David Attenborough: was already well known in 1965, having for more than a decade worked for the BBC

- Kearton brothers: although both Richard and Cherry are often credited with their photographs, Cherry was really the photographer where Richard was the all-round naturalist and writer.

Wonderful stuff, thank you. I have Eric Hosking’s owl book in my mainly African bird book collection. His and other early photography books fascinated me early on. Still do.