In 1973, I was stranded for several days on a small island in Witless Bay off the southeast coast of Newfoundland. I had gone there several times already that summer, conducting seabird surveys for the Canadian Wildlife Service. Landing on Green Island was sometimes difficult and the days were short as the local cod fishermen—Bill White and Henry Yard—who took me out and back liked to do so on certain tides to make the landings less dangerous. As the season was getting on and I still had a large part of the island to census, I decided, one day in June, to stay overnight so that I could get in 3-4 times as many hours on the island than was possible on a single visit. I took a tiny pup tent, two days’ food and water, a small camp stove full of fuel, a sleeping bag and a change of clothes as I knew I’d get wet.

My best-laid plans were thwarted by a fierce, unexpected storm that came to shore that night and lashed the island for more than a week. The storm was so wild that it prevented both the fishermen and an RCMP helicopter from picking me up. Often I had to spend hours in my little tent to stay dry and to keep from being blown off the cliffs. To pass the time I slept, made plans to stretch out my meagre food supply, and organized my field notes. I also built nooses of fishing line to catch some murres in case I needed to eat a few to survive as the storm was showing no signs of letting up. When cooped up in my little tent, I read, several times, the only book I had taken with me, Jane Goodall’s In the Shadow of Man, which had just come out in paperback. That book—and the experience of being stranded and rescued—had a profound effect on me.

My best-laid plans were thwarted by a fierce, unexpected storm that came to shore that night and lashed the island for more than a week. The storm was so wild that it prevented both the fishermen and an RCMP helicopter from picking me up. Often I had to spend hours in my little tent to stay dry and to keep from being blown off the cliffs. To pass the time I slept, made plans to stretch out my meagre food supply, and organized my field notes. I also built nooses of fishing line to catch some murres in case I needed to eat a few to survive as the storm was showing no signs of letting up. When cooped up in my little tent, I read, several times, the only book I had taken with me, Jane Goodall’s In the Shadow of Man, which had just come out in paperback. That book—and the experience of being stranded and rescued—had a profound effect on me.

Three things about Goodall’s book were important to my development and outlook as a scientist. First, and foremost, this was the first book I had read by a woman biologist/naturalist [1], and it was just as good as all the others. I think that Goodall’s book more or less marked a turning point for biology that has transformed the role of women during the past 50 years. Prior to Goodall’s book, I had read many of the recent and now classic ‘popular’ books by and about naturalists—Tinbergen, Lorenz, Lack, Robert Ardry, George Schaller, Ernest Thompson Seton, Albert Hochbaum, Fred Bodsworth, James Fisher and Roger Tory Peterson, to name just a few—all by men.

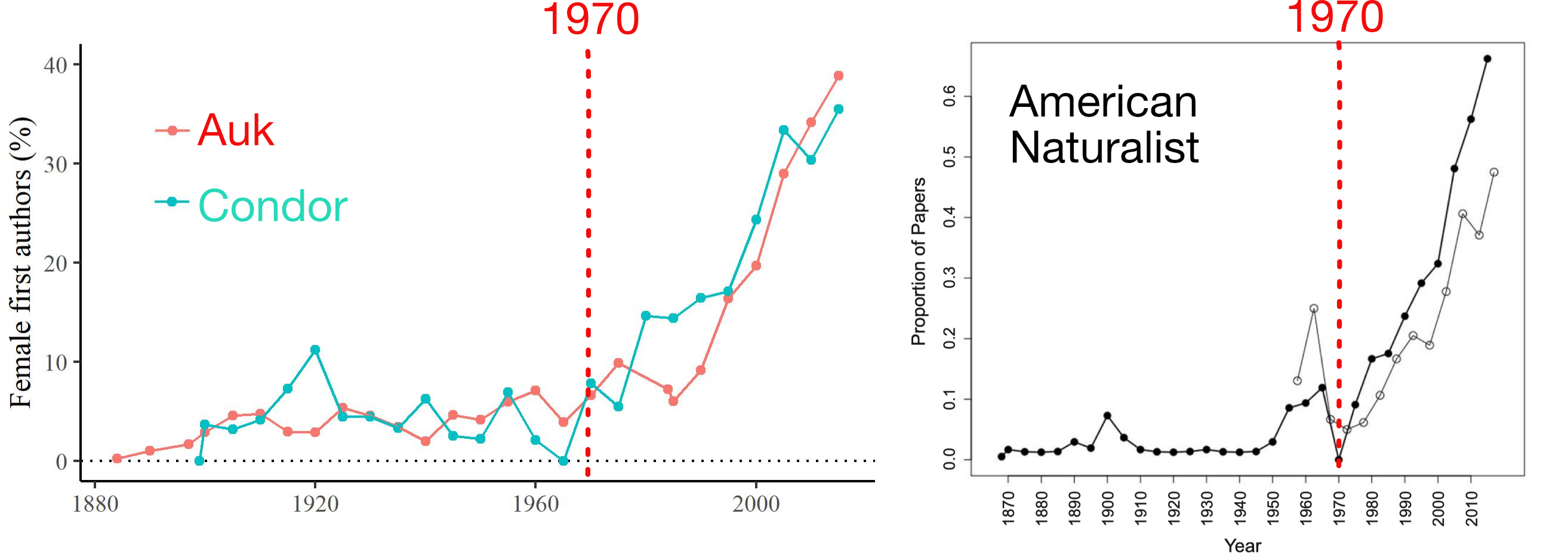

At that time, I knew of excellent recent work by women ornithologists—MM Nice, Mary Willson, Mercedes Foster, Janet Kear, Susan Smith—published in the bird journals, but they were very much in the minority. I have been looking at the publications by female ornithologists in The Auk and The Condor over the last 135 years and the trend—and the exponential increase in female authorships since 1970—is shown on the graph below, reflecting a similar trend in The American Naturalist.

My own experience as an academic reflects this welcome pattern as well. My first group of four graduate students were all men, all of whom went on to academic positions at excellent universities. My last (in both senses of the word) four graduate students were all female. It’s too early to tell what career path they will take but one of them just got a tenure-track job. This change in the composition of my research group since 1980 does not reflect any conscious attempt on my part to train women scientists—everyone that I took on as a graduate student was simply the best applicant at the time. During my first decade teaching (1980s), most undergraduate biology students were male; when I looked out on my 48-student History and Philosophy of Biology class last week I could count only 9 men.

Goodall’s book also reminded me how much fun it is to study animals close up, and how much better your insights can be when you can get extremely close to animals without seeming to disturb them. I enjoyed that aspect of studying seabirds that summer in Newfoundland, but also when studying both sandpipers and collared lemmings on the tundra at Churchill, Manitoba, the previous two summers. Such close observations of behaviours seemed to be important for testing hypotheses in the nascent field of behavioural ecology, especially where social interactions were concerned. Partly for that reason, I returned to the arctic with my newly-minted research group in 1980 as I knew the birds would be tame, could be watched at close distance, and could be followed for as long as we wanted on the open tundra. That was one of the reasons that we were able to document high levels of extrapair mating in Lapland Longspurs, years before DNA fingerprinting revealed that extrapair paternity was common in passerine birds [2].

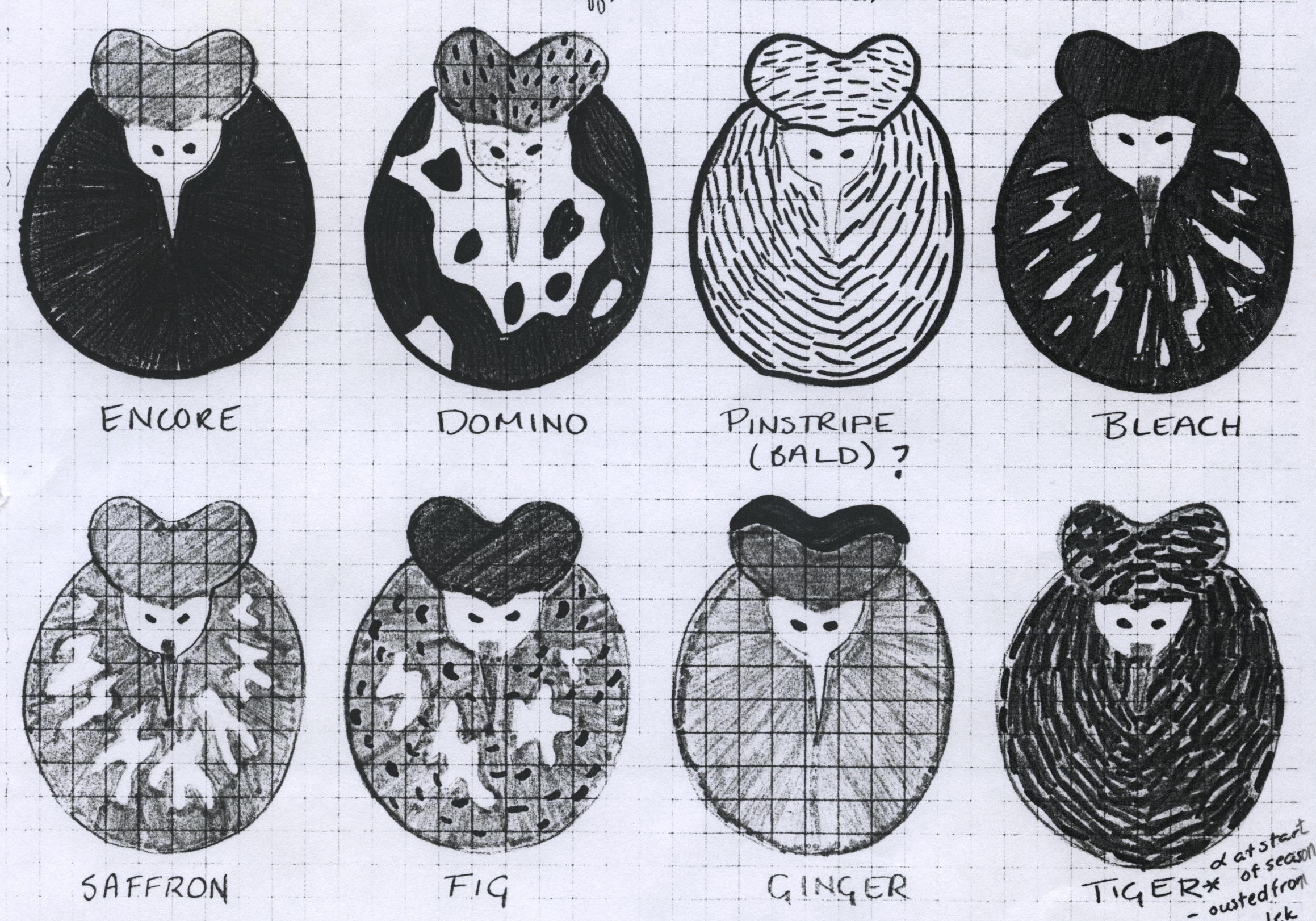

Finally, I was amused that Goodall had named all of the chimpanzees that she watched. I knew that Lorenz and others had named their study animals but I always thought that that would not be acceptable in a serious scientific study. Goodall reminded me that there was nothing wrong with making research fun and entertaining. Right away I started to give names to the pairs of seabirds nesting near my tent—was I going a little stir crazy? For the local pairs of puffins, black guillemots, herring gulls and common murres, I chose the names of my favourite folk and rock couples—Ian and Sylvia, Ike and Tina, (Peter) Paul and Mary, Jim and Jean, and Chuck and Joni [3]. Years later, we often gave names to our favourite pairs of Lapland Longspurs, Snow Buntings and Rock Ptarmigan. And, in the early 1990s, when we studied Ruffs on Gotland in the Baltic, we named each of the males on every lek and used hand-drawn mug shots to identify them individually.

Today (11 February 2019) is the UN-sponsored International Day of Women and Girls in Science, designed to celebrate and promote the roles of women in all of the sciences. While we have come a long way since Jane Goodall began working on chimpanzees, less than 30% of scientists worldwide are women, and there are still many barriers and sources of discrimination and gender bias in the sciences.

At the AOS meeting in Anchorage this year we will have some displays celebrating the roles of women in ornithology. For a long time, ornithology was largely a man’s game [4] but there have been some great, but relatively unknown, woman ornithologists in the past. I have tried to highlight some of their accomplishments on this blog [4]. In that same vein, I will devote all of March (Women’s History Month in the USA) to posts about the contributions of women to ornithology before Jane Goodall began studying chimpanzees.

SOURCES

-

Bronstein JL, Bolnick, DI (2018) “Her Joyous Enthusiasm for Her Life-Work…”: Early Women Authors in The American Naturalist. American Naturalist 192:655-663.

-

Burke T, Bruford MW (1987) DNA fingerprinting in birds. Nature 327:149–152.

-

Klopfer PH (1962) Behavioral aspects of ecology. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

-

Goodall JvL (1971) In the shadow of man. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Footnotes

- first book I had read by a woman biologist/naturalist: it’s only when writing this post today that I realized this. It certainly did not surprise me at the time.

- Chuck and Joni: my friends and I went to hear folk concert by the Mitchells at a coffee shop (either Penny Farthing or Riverboat) in Toronto’s Yorkville Village one night in 1967 or so. But the couple had broken up the day before and so a very nervous Joni did the gig on her own. She never looked back.

- extrapair paternity was common in passerine birds: see Burke and Buford (1987) for an early example

- largely a man’s game: see previous posts here, here, here, here, and here

IMAGES: all photos, the Ruff drawings, and the Auk/Condor graph by the author; American Naturalist graph modified from Figure 1 in Bronstein and Bolnick (2018)

CORRECTIONS: in the original post I forgot to add the Bronstein and Bolnick reference, the image sources, and the drawings of Ruffs. All added on 13 Feb 2019

Thoughtful post. I’ve always felt mostly like my own master, but of course am as buffeted by fate as anyone. I see that I started college right when women started on the publishing upswing. I had only male mentors and teachers but from them got the sense that I could become whatever I wanted to become. I wonder if there was an earlier change in the professors, then nearly all male, that helped with the earliest transition.

Wow, a wonderful post

I’m pleased that you were finally rescued from the island in the No. Atlantic!

Clearly, the thoughts set in motion by that experience have served you well. If nothing else, your posts are something to treasure.

Alan

Very interesting and educative.

Great read! I’m going to put Goodall’s book in my book-bucket-list ?