In 1850, an anonymous author published a superb diary of natural history observations called ‘Rural Hours by a Lady’ based on two years of exploring the woods and fields near Cooperstown, New York. The book was wildly popular, and it was not long before the author was revealed to be Susan Fenimore Cooper [1]. On page 146 she says:

It is well known that we have in the southern parts of the country a member of the Parrot tribe, the Carolina Parakeet. It is a handsome bird, and interesting from being the only one of its family met with in a temperate climate of the Northern Hemisphere. They are found in great numbers as far north as Virginia, on the Atlantic coast; beyond the Alleghanies, they spread themselves much farther to the northward, being frequent on the banks of the Ohio, and in the neighborhood of St. Louis. They are even found along the Illinois, nearly as far north as the shores of Lake Michigan. They fly in flocks, noisy and restless, like all their brethren…In the Southern States their flesh is eaten…Birds are frequently carried about against their will by gales of wind; the Stormy Petrels, for instance, thoroughly aquatic as they are, have been found, occasionally, far inland. And in the same way we must account for the visit of the Parakeets to the worthy Knickerbockers about Albany. [2]

Here, she correctly describes the bird as being most common in the southeastern states, though seen regularly as far north as the Great Lakes west of the Allegheny Mountains. What she did not know, of course, was that these were two subspecies, with different morphologies, ecologies and migratory strategies, as described below.

The Carolina Parakeet was still abundant throughout its range in 1850 but, like the Passenger Pigeon, was soon to be extirpated. The second-last individual was a female called ‘Lady Jane’ who died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1917; the last of its kind being Lady Jane’s mate, a male named ‘Incas’ who died there in 1918, one hundred years ago. Coincidentally, Incas died in the same cage where Martha, the last passenger pigeon, had died in 1914 [3]. There were reports of sightings in the wild for another 40 years or so, in Florida and Georgia, but none of those records were authenticated. Among the North American birds that have become extinct since the arrival of Europeans, the biology of the breeding biology Carolina Parakeet may be the poorest known [4]. And there is, surprisingly, only one photo of the bird in a natural-looking setting [5], taken by the irrepressible Robert Shufeldt in about 1900.

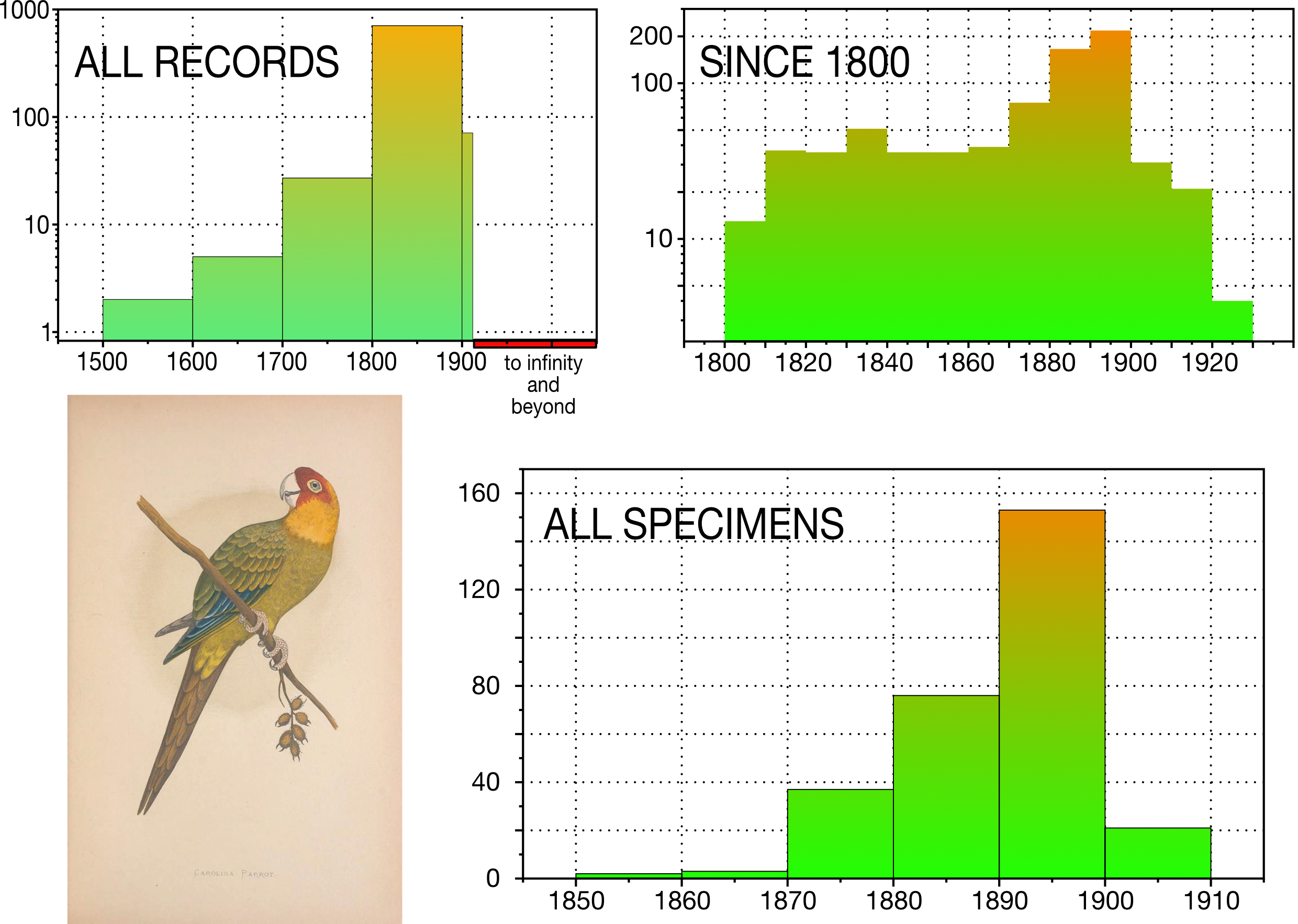

A recent pair of papers by Kevin Burgio and colleagues uses all of the known specimens and sightings of this bird to reveal some interesting insights into its distribution, ecology, and taxonomy. There were 401 of those sightings recorded between 1564 and 1944, and nearly 800 specimens in museums and private collections worldwide [6], almost all collected in the 1800s. As shown on the graphs below, the number of records climbed exponentially from 1500 to 1900, reflecting the increases in exploring the new continent, in writing about natural history, and in preserving ornithological data and specimens. There was an uptick in collecting, or at least preserving specimens, from 1870-1900 when it became clear that the bird was disappearing [6].

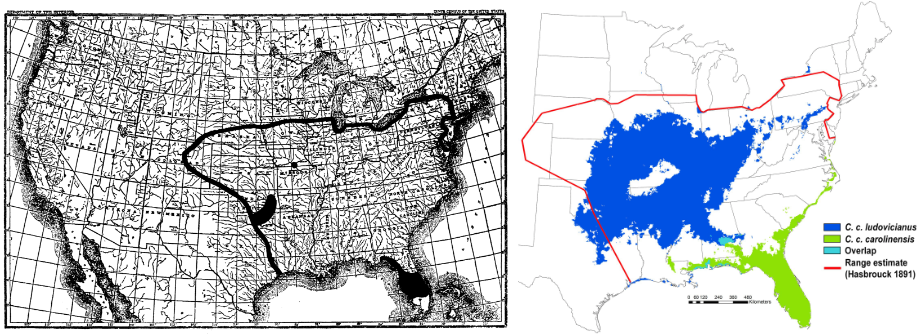

Analyzing records only from states where the parakeet was known to breed, Burgio and colleagues, georeferenced all the data and used 147 unique localities to create the species breeding distribution models shown on the map to the right below. The map on the left was produced in 1889 by Edwin Hasbrouck with the known range in his day (black shading) nicely matching the newly reconstructed ranges of the two subspecies.

Burgio and colleagues’ research also suggested (i) that the breeding range of this species was much smaller than previously thought, (ii) that the two subspecies, previously only vaguely defined by size and colour, actually had disjunct ranges and occupied somewhat different climatic niches, and (iii) that the western subspecies was almost certainly migratory where the eastern one was not.

The authors also hoped their analysis would help to inform current conservation practices in an effort to save the 8% of bird species currently threatened to disappear as a result of climate change. Parrots, in particular, are in bad shape, with 42% of species listed as threatened or endangered.

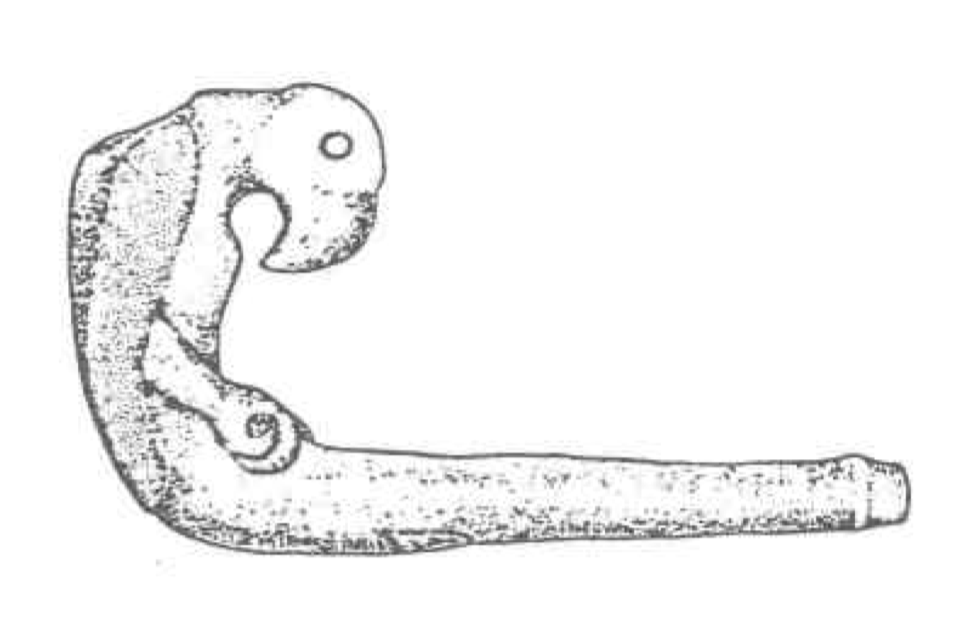

As much as I like those recent papers, I think it’s unfortunate that many biogeographers draw their maps as if animals obeyed political boundaries, as on the right-hand but not the left-hand maps above. The right-hand graph implies, for example, that the bird could never have crossed the US-Canada border as there was nowhere to go. Despite that, there is some evidence that it did occasionally occur in southwestern Ontario, possibly blown off course as Susan Cooper suggested above. At an archaeological dig at Grimsby, Ontario, for example, Walter Kenyon found a clay pipe that looks distinctly like a parrot, made by native peoples in the mid-1600s. And Rosemary Prevec found 3 Carolina Parakeet bones at a native site near London, Ontario, dated at around 1100 CE. Both of these findings are no more than suggestive and could have been obtained in trade with natives living further south.

Possibly more convincing are some observations that Samuel de Champlain recorded in his notes in 1615, in the woods near where I live in Kingston. He says that he “…penetrated so far into the woods in pursuit of a certain bird which seemed to be peculiar, with a beak almost like that of a parrot, as big as a hen, yellow all over, except for its red head and blue wings, which made successive flights like a partridge.” [8] There are definitely no other birds even remotely resembling that description in eastern Ontario today.

None of this nationalism is really important to our understanding of the bird’s ecology and demise, except to note that at one time the species was clearly widespread and mobile. What is important is an attempt to understand why they went extinct, as even by the middle of the 1800s it appeared to be declining in numbers [6].

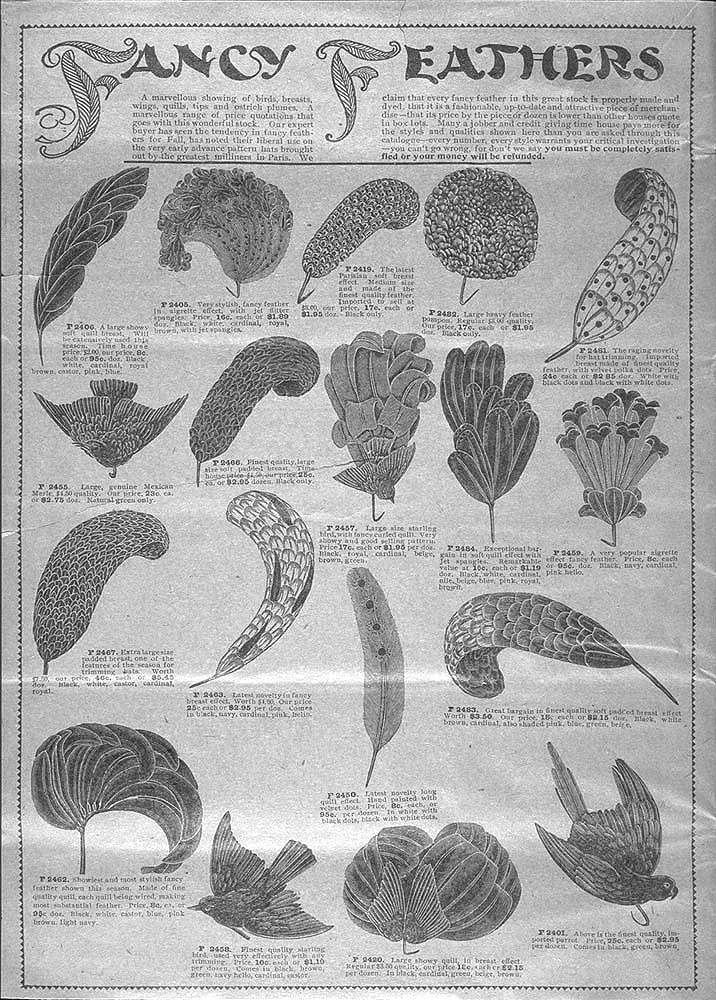

Burgio and colleagues point to habitat destruction and hunting as the likely causes. Not surprisingly, the parakeet’s feathers were prized for the millinery trade, with some reports suggesting that ladies hats were sometimes adorned with skins of the whole bird. The 1901 ad to the right, for example, shows a whole parrot (skin) in the lower right corner, for the bargain price of 25¢ a bird or $2.95 a dozen (about $7.50 and $88 in today’s currency). While the documentation is sketchy, it is also likely that this species was a popular cage bird in Germany as well as in North America. The only other known photo, besides Shufeltdt’s, is also one of a pet called ‘Doodles‘, kept by Smithsonian malacologist Paul Bartsch. In 1900, ‘doodle‘ meant ‘fool‘ and not the ‘absentminded scribble‘, Google commemorative, or online scheduler that it is today. And I wonder if Bratsch gave it that name to reminder him what fools we are when let any species go extinct.

SOURCES

- Anonymous [Cooper, SF] (1850) Rural Hours by a Lady. New York: G. Putnam.

- Burgio KR, Carlson CJ, Tingley MW (2017) Lazarus ecology: Recovering the distribution and migratory patterns of the extinct Carolina parakeet. Ecology and Evolution 7:5467–5475.

- Burgio K, Carlson C, Bond A (2018) Georeferenced sighting and specimen occurrence data of the extinct Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis) from 1564-1944. Biodiversity Data Journal 6:e25280.

- Cokinos C (2000) Hope Is the Thing With Feathers: A Personal Chronicle of Vanished Birds. New York: Penguin.

-

Fuller E (2013) Lost Animals: Extinction and the Photographic Record. London: Bloomsbury.

-

Greene WT, Dutton FGFG, Fawcett B, Lydon AF (1883) Parrots in Captivity, v. 2. London: George Bell and Sons.

- Hahn P (1963) Where is that Vanished Bird? Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [see this previous post for more on this book[

-

Kennedy CC (1984) Did Champlain stalk a Carolina Parakeet in southern Ontario in 1615? Arch Notes 84:55–62.

- McKinley, D. (1960) The Carolina parakeet in pioneer Missouri. The Wilson Bulletin 72:274–287.

- McKinley D (1977) Climatic relations, seasonal mobility, and hibernation in the Carolina Parakeet. Jack-Pine Warbler 55:107–124.

- Prevec R (1984) The Carolina Parakeet—its first appearance in southern Ontario. Arch Notes 84:51-54.

- Snyder NFR (2004) The Carolina Parakeet: Glimpses of a Vanished Bird. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Footnotes

- Susan Fenimore Cooper: was a superb naturalist, author, and artist whose work was overshadowed in more ways than one by that of her father, James. She deserves recognition and a separate essay on her own work, Stay tuned.

- Cooper quotation: from Anonymous 1850 page 146

- ‘Incas’ the parakeet: Like Martha, the last Passenger Pigeon, Incas was frozen and sent to the Smithsonian, but he was lost in transit (Fuller 2013)

- breeding biology poorly known: see Snyder (2004)

- Shufeldt’s photo: is one of a pair of pet birds that Shufeldt borrowed from his friend Edward Schmidt, and it took him hours to get it to sit still enough on a cocklebur to make a decent photo (Cokinos 2001). Both of Schmidt’s birds later died from chewing on the bars of their cage, possibly from lead paint poisoning (Fuller 2013)

- declining numbers by mid 1800s: see Hasbrouck (1889)

- records and specimens: see Hahn (1963), McKinley (1960, 1977) and Snyder (2004) for background

- Champlain quotation: from Kennedy 1984 page 55

IMAGES: first parakeet is by Robert Ridgway from Baird et al. (1905); graphs by the author based on data in Burgio et al. (2017, supplement)—parakeet is an engraving by Benjamin Fawcett in Greene et al. (1883); maps from the original papers; clay pipe from Kennedy (1984); millinery ad from the Smithsonian collection

There is another surviving photo of this now-extinct species.

It is a 1906 photo of the captive Carolina parakeet the owner Paul Bartsch had named “Doodles.”

Doodles died in 1914. By then he was recognized as one of the last captive individuals of the species.