In science, controversies often arise over complex issues when researchers approach a problem from different points of view, backgrounds, and philosophies—think, for example, of the debates over nature vs nurture, selection vs drift, group vs kin vs individual selection, gradualism vs punctuated equilibria, and mechanisms of sexual selection. As Ledyard Stebbins pointed out in 1982, the resolution of these controversies often settles somewhere in the middle because, in fact, both sides were correct to some extent [1]. Usually scientific controversies churn away towards some resolution with some degree of civility, at least in public forums. But not always…

I can still remember my first experience with a less-than-polite public argument among ornithologists. This occurred during a talk at an AOU meeting in the 1970s when two prominent systematists got into a shouting match during the question period after a graduate student’s talk. The issue was whether the approach taken by the student was correct, and the argument seemed to be between the cladists and the pheneticists.

I learned later that these clashes among systematists were commonplace in the 1960s and early 70s, during a period that was later referred to as the ‘Systematics Wars’ [2]. I was doubly surprised at such ad hominem attacks because the systematists that I knew from my years as a young volunteer and employee at the Royal Ontario Museum—L.L. Snyder, Jim Baillie, Jon Barlow, Jim Rising, and Allan Baker—seemed like the kindest of men. My own field of behavioural ecology, while often dealing in controversy, does not seem to have descended into the sort of personal attacks that characterized those arguments about systematics in the mid 1900s.

While scouring some older literature, we recently discovered [3] that the ‘Systematics Wars’ period was not the first time that avian systematists had engaged in rather nasty exchanges. During the 1830s, for example, two young brothers—Charles Thorold Wood and Neville Wood, tried to change the rules about naming birds in a way that involved heated debate, vitriol, and ad hominem attacks in their publications.

The Wood boys were wealthy, aristocratic, well-educated, and precocious. In 1835, when he was only 18, Charles published a quirky book—The Ornithological Guide—comprising 236 pages of poetry about birds, a compendium of ornithological books, each briefly reviewed, and a catalog (list) of the birds of Britain. Not to be outdone by his older brother, Neville published two books the next year, when he turned 18—British Song Birds and Ornithologists’ Text-book. British Song Birds alone ran to 400 pages, and, though it appeared not to include any novel observations, summarized much of what was then known about each species. Notably, none of the Woods’ publications included any illustrations.

The Woods felt that the names of birds—both scientific and English—were in a chaotic state and needed rules to make them more ‘scientific’. They were right. Even though Linnaeus had proposed his binomial system almost a century earlier [4], rules for zoological nomenclature that would provide some consistent structure and process were just beginning to be proposed in the 1830s [5].

The English names were more confusing and disorganized. In England, some birds were even given different English names in different parts of the country. In the 1800s, for example the European Bullfinch was variously called: Bull Flinch (Yorks), Bull Head, Bulldog, Bull Spink, Bully (Yorks), Thick Bill (Lancs), Alpe, Hoop, Hope (SW), Tope, Hoof, Cock Hoop (Hereford), Olf (E Suffolk), Nope (Staffs/Shrops), Mwope (Dorset), Mawp (Lancs), Pope (Dorset), Red Hoop (m, Dorset), Blood Olp (m, Surrey/Norfolk), Tawny (f, Somerset), Tony Hoop, Tonnihood (f, Somerset), Black Cap (Lincs), Billy Black Cap, Black Nob (Shrops), Monk, Bud Bird, Bud Finch, Bud Picker (Devon), Budding Bird (Hereford), Plum Bird, and Lum Budder (Shrops) [6].

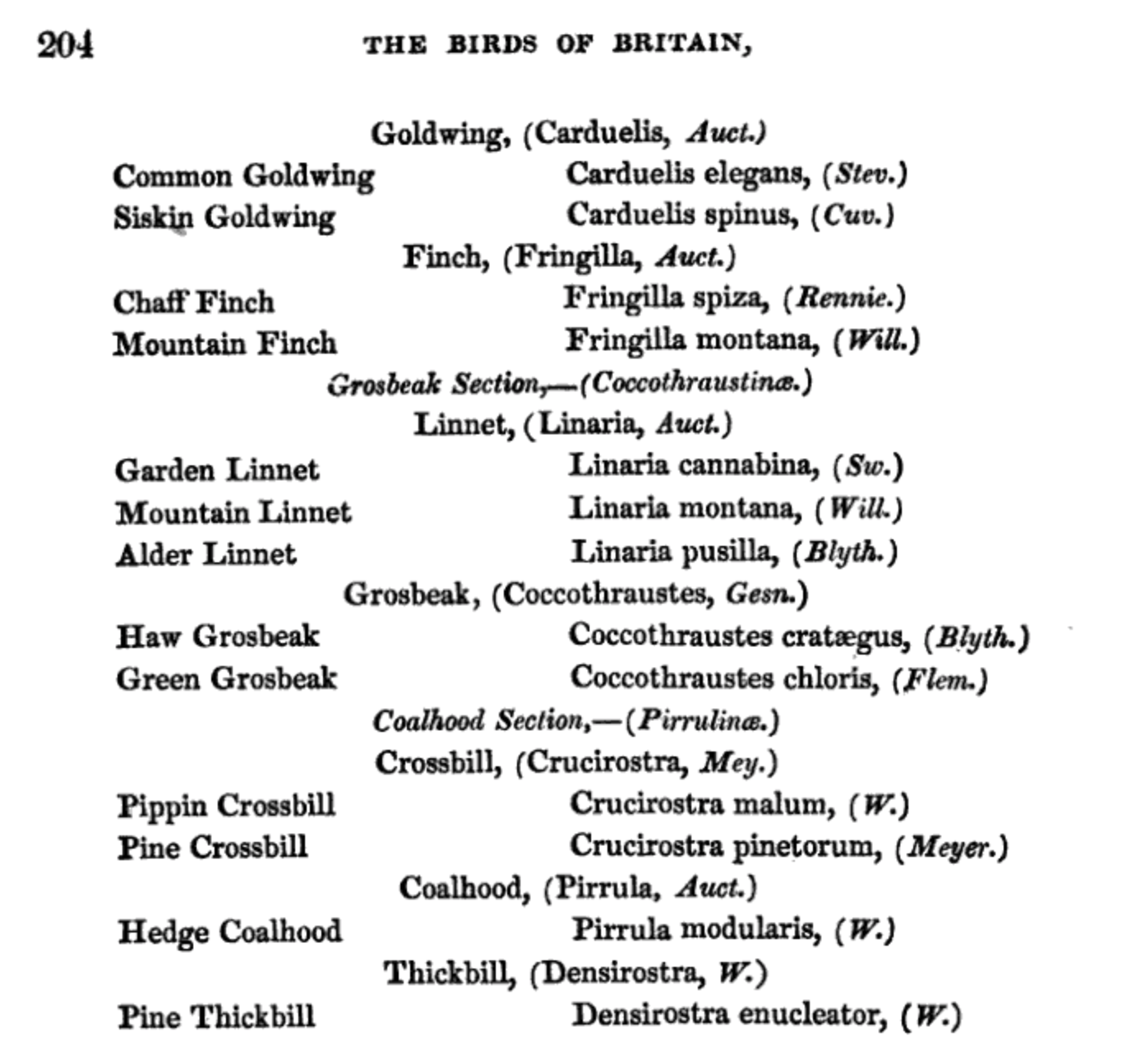

The Woods were sure that some logic and rules for the structure of English names were needed if ornithology was to develop as a science. As Neville said in one paper ”“If the proper English generic names were applied to every bird, how greatly would the acquisition of this fascinating study be facilitated! . . . By using the names which I have given above, this [confusion] is remedied, and all becomes plain and easy to understand.” [7] Their solution, for English names, was to make every bird within a genus have the same ’surname’, just as every genus had the same first name in the Linnaean system of Latin names. Thus, for example, Neville proposed:

It was also suggested at the time [8] that English names be cleansed of modifiers that indicate size, abundance, location, or honorific. Thus present-day names like Little Cuckoo, Common Cuckoo, Moluccan Cuckoo, and Klaas’s Cuckoo would all have to be changed in the Cuculidae alone. Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed, as Hugh Strickland argued that common names were “consecrated by usage as much as any other part of the English language”. As he noted “the science of ornithology does not suffer by this incorrect application of English names, because those familiar appellations have no real or necessary connection with science”. Despite his admonition, the English names of birds are still in a state of flux today and may always be.

The Woods’ proposals were well reasoned, if sometimes seeming to be a little bizarre today. But their suggestions were often presented in such a way that demeaned those who had different points of view. In the Preface to his Bird Song Birds, Neville says: “while I agree with my predecessors in many points, I have found much to correct, and still more to add, to the meagre and unsatisfactory accounts of most of our British Ornithologists.” Ouch!

Neville’s review of Eleazar Albin’s Natural History of Birds claimed that it was “of no use in the present day” and of Jennings Ornithologia that he ”never had the misfortune to meet with a book so full of errors . . . We should have considered such a work beneath our notice, as it is impossible it can have the smallest connection with the advancement of Ornithology”. [9] Their writings are sprinkled with derogatory epithets and harsh criticism that even today strikes me as ungentlemanly, possibly simply the result of the Woods being callow youth [10].

Possibly because they gained few converts, and appear not have been well liked, both Charles and Neville drifted off to other pursuits before their 35th birthdays, never again to write about birds or to heap opprobrium on their fellow ornithologists. Charles published his last paper on birds (again on nomenclature) when he was 19 and then seems to have vanished from the public record; Neville trained as a doctor, and at the age of 26 moved to London where he practiced the new medical system called ‘homeopathy’ for the rest of his life. At least if he had stayed with birds he would have done something potentially useful.

Stebbins ended his 1982 address to the American Association for the Advancement of Science [11] by saying that: “My final hope is that evolutionists having different backgrounds and viewpoints will reduce their rivalry and collaborate increasingly in zealous research toward finding answers to these and other questions of major significance.” This was a noble sentiment but ignored those ineluctable human (or at least male) foibles of ego, ambition, and competitiveness. I would argue that controversies are are valuable part of scientific progress, and I have certainly enjoyed watching the systematics wars from the sidelines. We should always try to maintain civility but the controversies that arise from different points of view often move a field forward faster and more profitably than would the absence of skepticism about published research.

SOURCES

-

Albin E (1731) A Natural History of Birds : Illustrated With a Hundred and One Copper Plates, Curiously Engraven From the Life. Vol I. London: Printed for the author and sold by William Innys in St. Paul’s Church yard, John Clarke under the Royal-Exchange, Cornhill, and John Brindley at the King’s Arms in New Bond-Street. <available here>

-

Anonymous “N. F.” (1835) Remarks on vernacular and scientific ornithological literature. The Analyst 2: 305–307.

-

Birkhead TR, Montgomerie R (2016) A vile passion for altering names: the contributions of Charles Thorold Wood jun. and Neville Wood to ornithology in the 1830s. Archives of Natural History 43:221–236.

-

Greenoak F (1997) British Birds: their folklore, names, and literature. London: Christopher Helm.

-

Jennings J (1829) Ornithologia, or, the Birds: A Poem, in Two Parts : With an Introduction to Their Natural History; and Copious Notes. London: Sherwood, Gilbert, and Piper. <available here>

- Stebbins GL. (1982a). Modal themes: a new framework for evolutionary synthesis. in Milkman R (Ed.), Perspectives on Evolution (pp. 12-14). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates.

- Stebbins GL (1982b) Perspectives in evolutionary theory. Evolution 36:1109–1118.

- Sterner B, Lidgard S (2017) Moving past the Systematics Wars. Journal of the History of Biology https://doi.org/10.1007/s10739-017-9471-1

- Wood CT (1835) The ornithological guide: in which are discussed several interesting points in ornithology. London Whittaker. <available here>

- Wood N (1836a) British song birds: being popular descriptions and anecdotes of the choristers of the groves. London: John W. Parker. <available here>

- WOOD N (1836b) The ornithologists’ text-book: being reviews of ornithological works on various topics of interest. London: John W. Parker. <available here>

Footnotes

- Stebbins (1982a) argued that modal themes were often the correct resolution of these conflicts, as has proven to be more-or-less the case in all the controversies listed here, with the notable exception that group selection is still controversial (and mistaken in my opinion)

- see, for example, Sterner and Lidgard (2017) for an overview

- Tim Birkhead made this discovery while researching for the project on Francis Willughby that he wrote here about a few weeks ago

- Linnaeus Systema Naturae had built on Willughby and Ray’s attempt at organizing and logically giving each species a scientific name (Ray (1678), but in the subsequent century there were many attempts to apply Linnaeus system to the birds with each author claiming authority and none of today’s rules about priority, coordination or homonymy.

- The International Zoological Congresses of 1889 and 1892 saw the first discussions about some universal rules in zoology but the International Rules on Zoological Nomenclature were not published until 1905. Earlier, the ornithologist Hugh Strickland had published a set of 22 rules for the formulation of scientific names that formed some of the basis for this later code.

- the sex that was so named, and the county or general area where each name was used, are shown in brackets, from Greenoak (1997).

- quotation from Wood 1835a: 238

- this was proposed in a paper in The Analyst signed simply N.F. (Anonymous 1835), who I think may well have been Neville Wood based on what N.F. says and the style of writing.

- see Birkhead and Montgomerie (2016) for some other gems. The paper is behind a paywall but send me an email if you cannot get it and would like a copy.

- ‘callow’ seems to me to be a particularly good adjective to describe these young men, as it refers to someone who is “inexperienced and immature”, but in the 17th century the term was applied to birds, and meant ‘without feathers’ or immature and not ready to fly.

- presented on 7 Jan 1982, at a AAAS symposium marking the 100th anniversary of the death of Charles Darwin; quotation from Stebbins (1982b)

COMMENTS