By Brooke Goodman

Related paper: Humans outperform Merlin Sound ID in field-based point-count surveys by Brooke D. Goodman, Kyle A. Lima, Seth Benz, Nicholas A. Fisichelli, and Justin Kitzes. Ornithological Applications.

It’s a morning many birders dream of: You wake up, make your morning coffee, and settle in to read the eBird rare bird alerts that rolled into your inbox as you slept. Suddenly, you see something that makes your heart race—a rare bird you’ve never seen before was sighted in your area! You excitedly scroll through the sighting information, only to be stopped in your tracks by a phrase that haunts many birders: “Identified by Merlin.“

Merlin’s sound classifier feature has revolutionized interaction with the avian world since its release in 2021. It works by learning the unique features of a species’ vocalization, and then recognizing those features in user-recorded spectrograms, allowing someone to record birds and view species identifications in real time. Ornithologists have been using neural networks to analyze soundscapes for years, but Merlin brought this technology into the pockets of the general public.

Along with endlessly entertaining birders, Merlin presents as a seemingly ideal solution to perpetual problems in bird surveying. Experienced point counters are hard to find, expensive to hire, and can have huge variation in detection abilities. Passive acoustic monitoring techniques address some of these issues, but come with their own costs and complications. Merlin Sound ID could be a part of the solution to these problems by functioning as a no-cost, in-field observer with consistent performance.

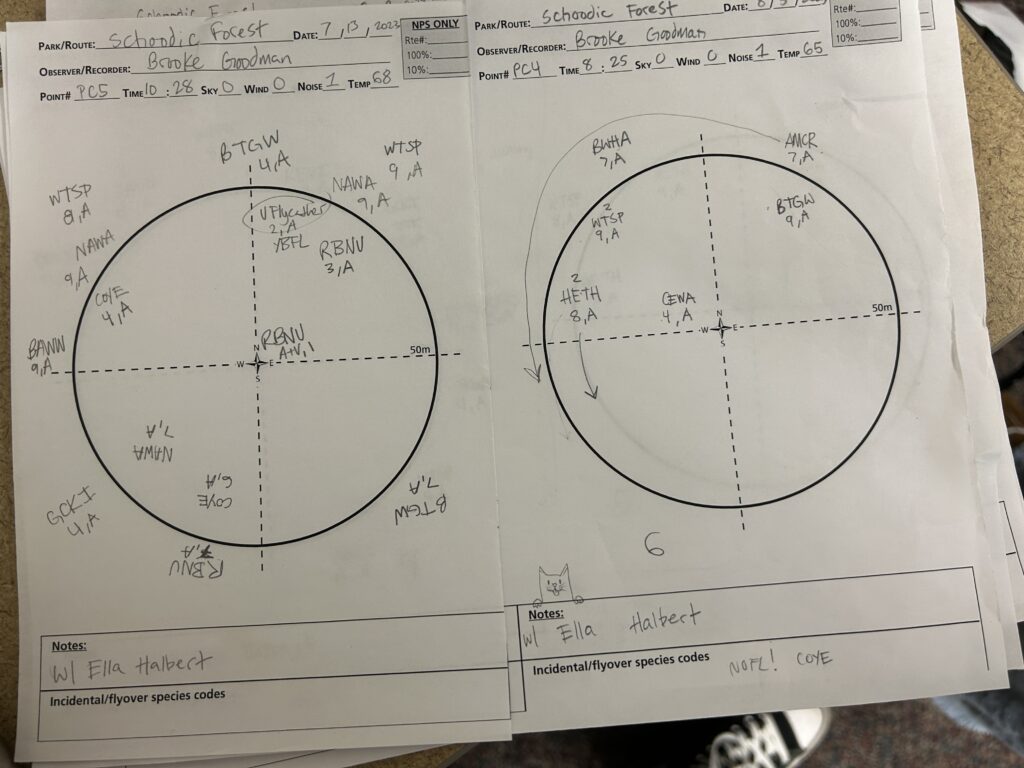

However, before integrating Merlin into scientific research, the performance of Merlin and humans must be quantitatively compared. Merlin is not perfect; you may have experienced it identifying Tamiasciurus hudsonicus (Red Squirrel) as Dryobates villosus (Hairy Woodpecker), or your loud birding friends (guys, you’ll scare them away!) as Corvus ossifragus (Fish Crows), leading to the aforementioned hesitation many birders have when hearing something was identified solely by Merlin. But, identifications by humans are also far from perfect, and a formal comparison could reveal the strengths and weaknesses of the two methods. In 2023, staff at the Schoodic Institute and I set out to conduct this comparison through 144 paired human and Merlin point counts. Our goals were to evaluate differences between species identified, the number of individual detections, and precision for humans and Merlin. We also examined the consistency of Merlin across different devices.

The biggest difference we found between humans and Merlin was the number of individual detections throughout the course of the study. Humans made 382 detections compared to 222 by Merlin; if a bird was present within the survey radius, a human was 72 percent more likely to detect it. Merlin detected 12 false positive species over the course of the study; these were species that, despite being reported by Merlin, were not truly present. However, when comparing the total percentage of individual identifications that were correct (precision), rates were similar with 92 percent for humans and 86 percent for Merlin. There were four species that Merlin identified correctly that humans missed, and eight species that were only ever identified correctly by humans. Interestingly, Merlin generated different species lists for 57 percent of point counts when running on two different devices at the same time. This could be due to differences in microphone quality or device positioning.

Considering these results, we propose Merlin not as a replacement for human point counters, but as an aid to increase detection probability for surveys. Merlin can act as a second observer with humans acting as primary observers, arbitrating disagreements between devices and evaluating possible false positives when needed. Surveys using Merlin need to test inter-device variability just like they would inter-observer variability, and should keep in mind that the classifier will perform differently for different species and at different levels of background noise.

Merlin isn’t perfect, but neither are we. With further research into this methodology, technology like Merlin could help address some of the challenges associated with point-count based research. You’re right to be skeptical of any identifications made solely by Merlin, but with human verification, it is a powerful tool to research birds and, of course, find the rare species you need for your life list.

Great idea and project. Merlin is even worse in places like Ecuador! However, I wonder if Merlin might well improve faster than any human. I remember Ted Parker claimed to know about 3000 birds by sound. I probably once knew about 500, but my aging brain no longer matches names to sounds I am sure I once knew. Algorithms last longer that elderly neuronal synapses, it seems. Go Merlin, but yeah, try to learn the songs yourself, too!

Excellent and timely. Need to get these results out to the general birding public (e.g., ABA and ebird users).

Interesting, important, and timely. Well done!