On the 18th of June 1858, one hundred and sixty years ago today, Darwin claims [1] to have received that fateful letter from Alfred Russel Wallace—probably the most famous letter in the history of science. The original letter was lost but it was transcribed and read to the Linnean Society of London on 1 July and published later in their journal. That letter is well worth reading, especially because it contains some interesting insights into avian ecology. While Wallace had some useful ideas relevant to natural selection, it could be argued that his argument was not nearly as well-formed as Darwin’s [2]. In a way, his ecological and biogeographical insights are more original, in my opinion.

Wallace wrote that letter on Ternate in the Mollucas in February 1858, sent it out on a mail steamer on 5 April. He was in the South Pacific for 8 years on a collecting trip, in part to obtain specimens that he could sell back in England but also to gather material for books that he thought, rightly so, would provide him with a lifetime of fame and fortune. He brought home more than 125,000 specimens, including more than 8000 bird skins.

I found three things to be remarkable about Wallace’s letter. First, he develops some of the same ideas about selection as Darwin, and uses some of the same language: “state of nature”, “struggle for existence”, “stability of species”, “geometrical ratio”, “origin of…species”, “conditions of existence”, and “superior varieties.” These are not phrases you would be likely to read in a recent paper on evolutionary biology, but may well have been argots of the scientific literature in the 1800s.

Second, he makes clear his objections to Lamarck’s ideas:

The hypothesis of Lamarck—that progressive changes in species have been produced by the attempts of animals to increase the development of their own organs, and thus modify their structure and habits—has been repeatedly and easily refuted…the view here developed renders such an hypothesis quite unnecessary, by showing that similar results must be produced by the action of principles constantly at work in nature. [3]

And third, he is remarkably insightful and creative about what today we would call evolutionary ecology with respect to passenger pigeons, woodpeckers, and clutch size.

On clutch size, he makes the perceptive observation that a species’ population size—and rate of increase—has nothing to do with the number of offspring in a brood:

…large broods are superfluous. On the average all above one become food for hawks and kites, wild cats and weasels, or perish of cold and hunger as winter comes on. This is strikingly proved by the case of particular species; for we find that their abundance in individuals bears no relation whatever to their fertility in producing offspring. Perhaps the most remarkable instance of an immense bird population is that of the passenger pigeon of the United States, which lays only one, or at most two eggs, and is said to rear generally but one young one. [3]

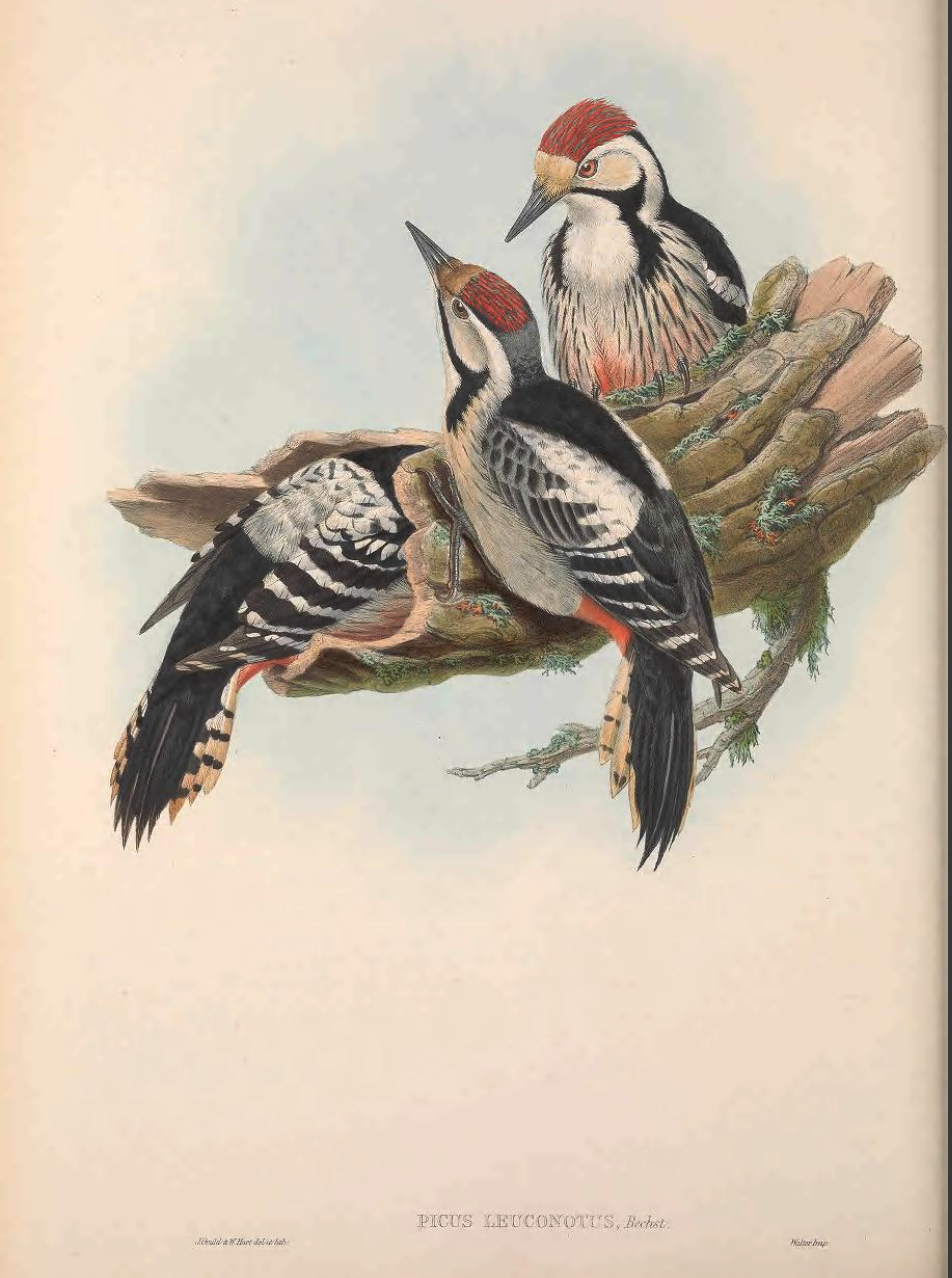

On woodpeckers, he argues that they are more scarce in the temperate zone than in the tropics due to the uncertainty of overwinter food in the north, and the various morphological adaptations that would make long-distance migration difficult. I don’t even know if these observations are true, but the idea is immensely creative and demonstrates his excellent ecological insights:

Those whose organization does not permit them to migrate when their food becomes periodically scarce, can never attain a large population. This is probably the reason why woodpeckers are scarce with us, while in the tropics they are among the most abundant of solitary birds. Thus the house sparrow is more abundant than the redbreast, because its food is more constant and plentiful,- seeds of grasses being preserved during the winter, and our farm-yards and stubble-fields furnishing an almost inexhaustible supply. [3]

On the Passenger Pigeon, he reasons—correctly, I think—that its unbelievably huge populations were a product of the bird’s ability to move efficiently to track the vagaries of its occasionally superabundant food supply:

Perhaps the most remarkable instance of an immense bird population is that of the passenger pigeon of the United States, which lays only one, or at most two eggs, and is said to rear generally but one young one. Why is this bird so extraordinarily abundant, while others producing two or three times as many young are much less plentiful? The explanation is not difficult. The food most congenial to this species, and on which it thrives best, is abundantly distributed over a very extensive region, offering such difference of soil and climate, that in one part or another of the area the supply never fails. The bird is capable of a very rapid and long-continued flight, so that it can pass without fatigue over the whole of the district it inhabits, and as soon as the supply of food begins to fail in one place is able to discover a fresh feeding-ground. [3]

Like his contemporaries, however, Wallace reasoned that this species’ populations were just too big to fail: “This example strikingly shows us that the procuring a constant supply of wholesome food is almost the sole condition requisite for ensuring the rapid increase of a given species, since neither the limited fecundity, nor the unrestrained attacks of birds of prey and of man are here sufficient to check it. In no other birds are these peculiar circumstances so strikingly combined.” [3] This is one of those rare cases where we could actually learn from history and maybe not repeat Wallace’s mistake in our dealings with other species.

SOURCES

-

Bock WJ (2009) The Darwin-Wallace myth of 1858. Proceedings of the Zoological Society 62:1–12.

- Davies R (2008) The Darwin conspiracy: origins of a scientific crime. London: Golden Square Books

-

Davies R (2012) How Charles Darwin received Wallace’s Ternate paper 15 days earlier than he claimed: a comment on van Wyhe and Rookmaaker (2012). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 105:472–477.

-

Darwin CR, Wallace AR (1858) On the tendency of species to form varieties; and on the perpetuation of varieties and species by natural means of selection. Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London, Zoology 3:46–50.

-

Davies R (2012) How Charles Darwin received Wallace’s Ternate paper 15 days earlier than he claimed: a comment on van Wyhe and Rookmaaker (2012). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 105:472–477.

- Gould E, Gould J, Lear E (1837) The Birds of Europe. (v. 1-5). London: pub. by the author.

-

Smith CH (2013) A further look at the 1858 Wallace–Darwin mail delivery question. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 108:715–718.

Footnotes

- Darwin’s claim about Wallace’s letter: Davies (2008) in particular, claimed that Darwin received the letter earlier and plagiarized it in his own notes so that he could claim priority, This seems highly unlikely to me, based on what I know of Darwin’s character and what Darwin himself says about the letter. van why and Rookmaaker (2012) present a convincing counter argument (but also see Davies 2012)

- Wallace’s ideas on natural selection: see Bock (2008) for details on what Wallace did have to say about selection

- Quotations: are all from the transcribed version of Wallace’s letter, available here