Tomorrow is Christmas Day and, like last year, I am spending the holidays in the north woods, a few km south of the southern tip of Algonquin Park, on the southern edge of the Canadian Shield. I wrote about the Twelve Days of Christmas song a year ago and am repeating that essay here with some new pictures and a few additions—including some details about those Three French Hens—that I have learned about over the past year.

I particularly like The Twelve Days of Christmas because the words are secular, even though there are myriad religious interpretations [1]. The song originated in an 18th century memory game, celebrating an annual period of drunkenness and merrymaking sandwiched between two religious feasts. Many of those twelve days are about birds that were prized for the table. In mediaeval England, this period following Christmas was presided over by the Lord of Misrule and in Scotland by the Abbott of Unreason, both titles that I would be proud to bear.

The words to this Christmas song were first published in English in the late 1700s as a rhyme in a book called Mirth without Mischief, likely derived from a much older French song of similar structure and content, Les Douze Mois. The now familiar tune was not written until 1905 by the English composer Frederic Austin who adapted it from a traditional English folk melody.

As you will recall—for by now it’s an ear worm that you can’t stop humming—the 12 days begin on Christmas Day with the partridge. On 5 or 6 of the following days, the gifts are birds, interrupted musically, thematically and enigmatically by those 5 golden rings. I have no idea why the first 7 gifts are birds, but I expect there are traditional and psychological reasons that have been claimed for this but they are probably all about food. There have also been many Christian interpretations of this song but really no evidence to support any of them. I find the secular interpretations to be far more interesting and valid.

In the almost 238 years since the rhyme was first published in English, there have been at least 20 different versions of the words, especially with respect to the birds. Some of these variants are undoubtedly Mondegreens [2], but they were often probably just attempts to make the words more relevant to a contemporary audience.

The PARTRIDGE—on the first day of Christmas— was always a partridge, except in Scott’s 1892 version where it was a “very pretty peacock.” Some authors claim that the partridge was the Red-legged Partridge (Alectoris rufa) a very popular game bird that had just been successfully introduced to England from France in about 1770, and much more likely to perch in trees than the native and abundant Grey Partridge (Perdix perdix). But what about that pear tree, which again has been often claimed to have religious connotations. The French poem that may have been the basis for the English rhyme has a partridge representing the first month “Un’ Perdix Sole’. That version says that the bird flies in the woods (‘qui vol dans les bois’). The Perdix is the Grey Partridge, which in Old French was spelt ‘perdrix’ or ‘pertriz’, pronounced something very close to ‘pear tree’. I wonder if the English rhyme was originally ‘partridge and a perdrix’, though that would be two birds for day one. Nonetheless it seems to me quite likely that the pear tree was actually the perdrix, and had nothing at all to do with pears or trees.

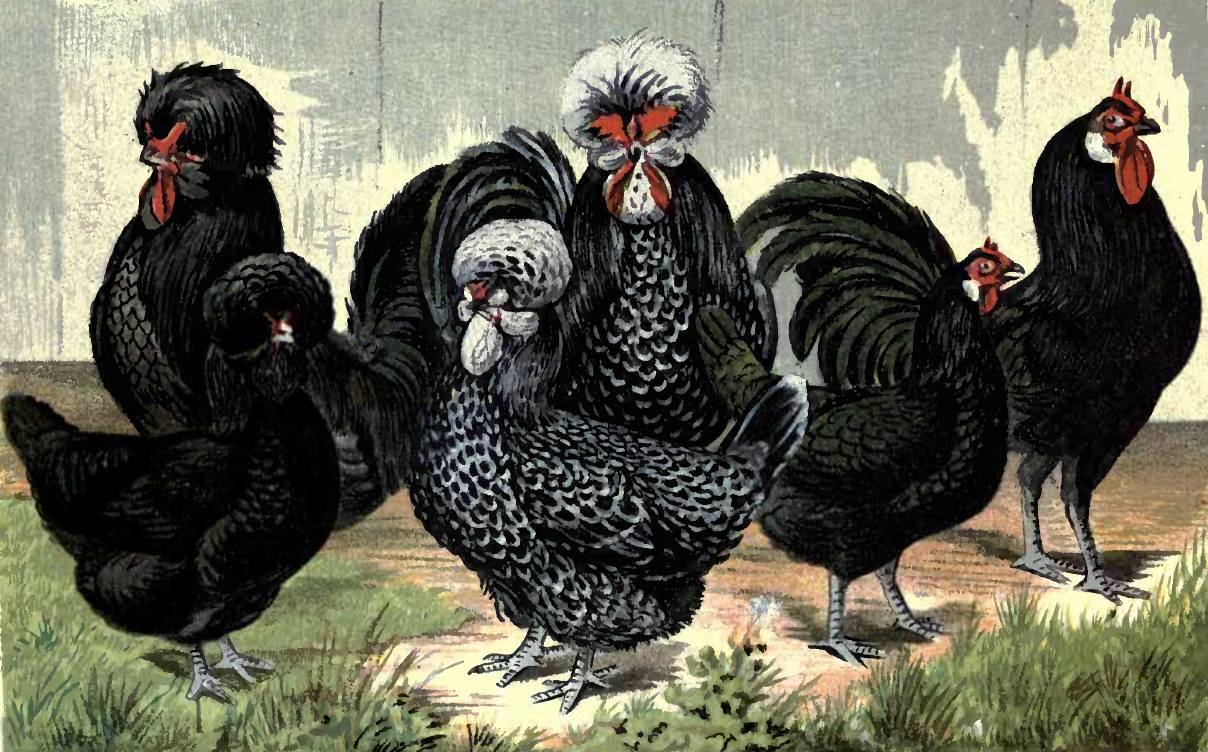

On day 2, the TURTLE DOVES were French hens in one 1877 version, and the FRENCH HENS on day 3 were once ‘fat hens’ in 1864, and turtle doves in 1877. There’s a theme here as the first 3 birds were highly prized for the table, an excellent start to a period of feasting.

But why ‘French‘ hens? The Latin word for chicken is gallus and, as a result, the scientific name is Gallus gallus [3]. In Roman times, France was Gaul, and people who lived there were Gallic. It seems that the simple word association between the homonyms Gallus and Gallic irrevocably associated the fowl with France. Indeed, a rooster was often a decorative ornament on church bell towers in France during the Middle Ages, and the Gallic Rooster (see photo, right) was an important symbol during the French Revolution.

But why ‘French‘ hens? The Latin word for chicken is gallus and, as a result, the scientific name is Gallus gallus [3]. In Roman times, France was Gaul, and people who lived there were Gallic. It seems that the simple word association between the homonyms Gallus and Gallic irrevocably associated the fowl with France. Indeed, a rooster was often a decorative ornament on church bell towers in France during the Middle Ages, and the Gallic Rooster (see photo, right) was an important symbol during the French Revolution.

But also, when the Twelve Days rhyme was written, French hens were a prized table bird in both France and England. The breed Bresse Gauloise, for example, was sometimes called the ‘queen of poultry and the poultry of kings’. This breed originated in France in the late 16th century. La Fleche is also an ancient French breed from the Loire region of western France, and was renowned for its delicate flesh. During the 16th century hens from France were a luxury import from France. In the 19th century, the Houdan, another old breed from west of Paris, was one of the main meat breeds of France, and was imported to North America in 1865.

We humans are inordinately fond of eating chickens and a recent report suggests that the 60 billion chickens that we slaughter every year may turn out to be the paleontological signal of the Anthropocene. Of all the birds mentioned in the Twelve Days of Christmas, I doubt that anyone in 1800 could have predicted that the French hens and their kin would someday become the most abundant bird in the world, by at least an order of magnitude.

The CALLING BIRDS of day 4 are the most interesting to me as the original said ‘colly birds’ and subsequent variants said the birds were ‘canary’, ‘collie’, ‘colley’, ‘colour’d’, ‘curley’, ‘coloured’, ‘corley’, and finally ‘calling’ by Austin in 1909 published with his new tune. I am surprised no one ever suggested ‘collared’. The original ‘colly bird’ was the European Blackbird (Turdus merula) as ‘colly’ meant ‘black’ as in ‘coaly’, and is why border collies bear that name. The subsequent versions are undoubtedly the result of mis-hearings and misinterpretations.

The gift for day 5 in the original and modern version is GOLDEN RINGS but several sources claim that these are birds too, probably European Goldfinches, which were called goldspinks in the 1700s. Others have argued that these were Ring-necked Pheasants which have been claimed to have golden rings around their neck (but they don’t). The pheasant interpretation matches the culinary theme of the other 6 birds in the song, but the goldfinch was a popular cage bird in the 18th century. The melodic break in the song suggests a change of theme but the melody was added more than a century after the words.

The birds of days 6 and 7—the GEESE A-LAYING and the SWANS A-SWIMMING—round out the culinary theme before the song turns to dance providing some exercise after all that feasting, and chores that may have been neglected.

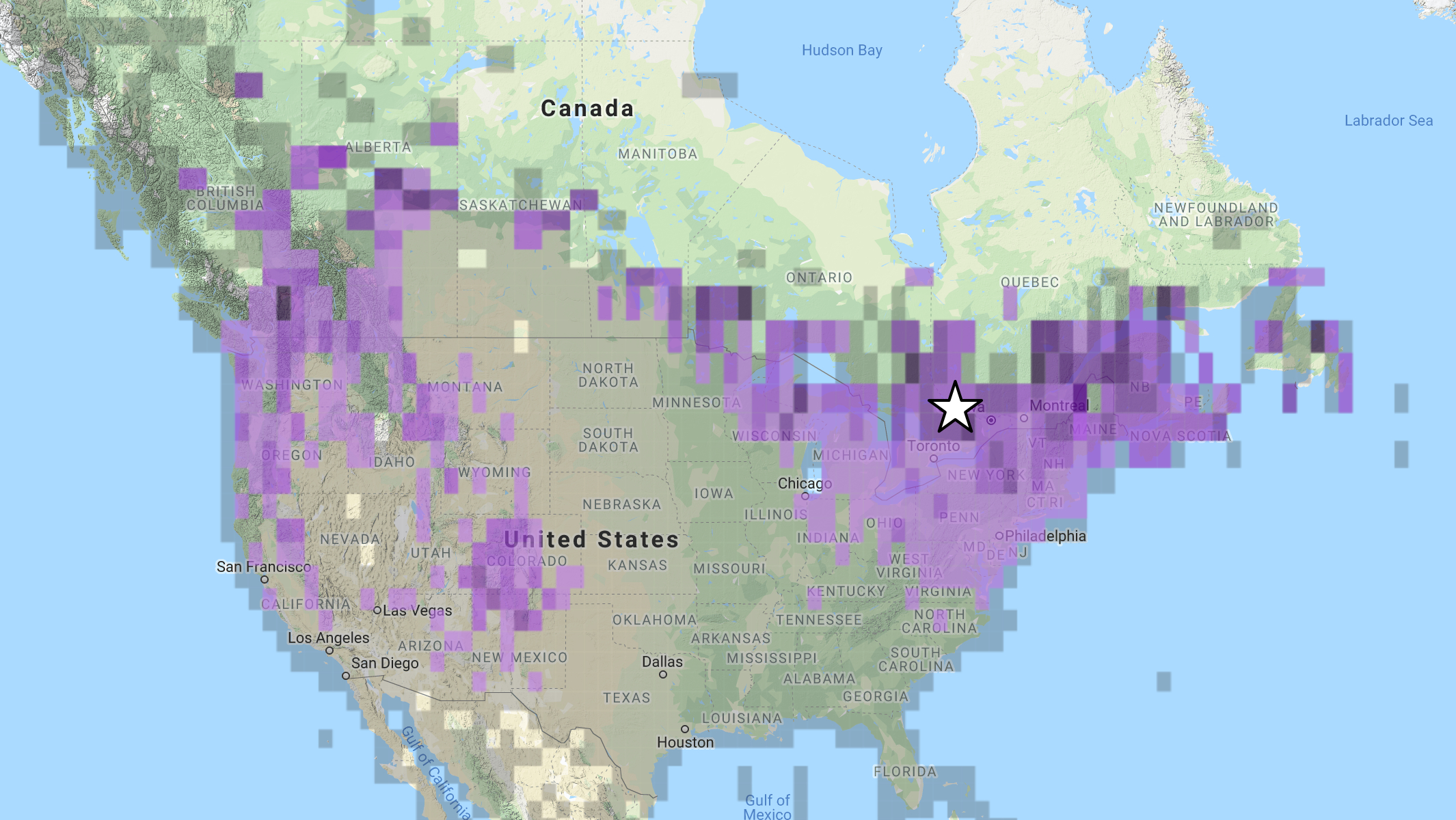

Here in the north woods the colly birds (and the only birds really calling) are Ravens, and the only ‘partridge’ is the Spruce Grouse, as all the geese, swans, doves, and goldfinches have departed for more southern winter quarters. The good news, this year, is that there are Pine and Evening Grosbeaks in the neighbourhood, as well as both species of redpoll. E-bird (map below) shows that I am well-situated (white star) to see Evening Grosbeaks in numbers, a bird I have seen only occasionally for the past 50 years.

Counting the 5 golden rings, there are 28 individual birds in The Twelve Days of Christmas but I will be lucky to see even 28 individual birds on a day out in the winter woods here, where the temperature will be below freezing—and sometimes way below—for the next four months. That will not stop the 75 or more people who will gather in Algonquin Park for the Christmas Bird Count (CBC) on 29 December, where they will probably record fewer than 28 species [4] in a hard day’s work on foot, skis and snowshoes. This will be the 45th consecutive CBC for Algonquin Park and the 118th CBC since Frank Chapman started the count in 1900.

During the 19th century, the Christmas Side Hunt was a popular competition to gather game for the table during the 12 days of Christmas. Chapman, however, was a conservationist who saw great value in watching rather than hunting birds. That first CBC involved only 27 birdwatchers at 25 sites from Toronto, Ontario, to Pacific Grove, California, laying the foundations for what we now call citizen science.

SOURCES

-

Ray J (1676) Ornithologiae libri tres: in quibus aves omnes hactenus cognitae in methodum naturis suis convenientem redactae accuratè descripbuntur, descriptiones iconibus. London: John Martyn.

Footnotes

- myriad religious interpretations: see here, for example

- Mondegreen: Jimi Hendrix created a classic ‘Mondegreen’ when he sang (at least to my ears) “Scuse me while I kiss this guy” in his song ‘Purple Haze’, first released as a single in 1967. Rock lyrics are a rich source of Mondegreens—words or phrases that are misheard—as Sylvia Wright, who coined the term, did when she heard a Scottish ballad say “Lady Mondegreen” when it actually said “laid him on the green”.

- Gallus gallus: Linnaeus established this in 1758, but John Ray called them Gallus gallinaceus in 1676 and the name had clearly been in use for some time in England and Europe. Gallus gallus is, of course, the scientific name of the wild ancestor of the domestic hen, the Red Junglefowl of southeast Asia

- fewer than 28 species: that’s what I predicted for last year and they did indeed record that number, and 4704 individuals. Their sighting rate was 31 birds per party hour and that was well above the average of 25. That’s a lot of work (maybe 3 birds per hour per party), but a great day out.

COMMENTS