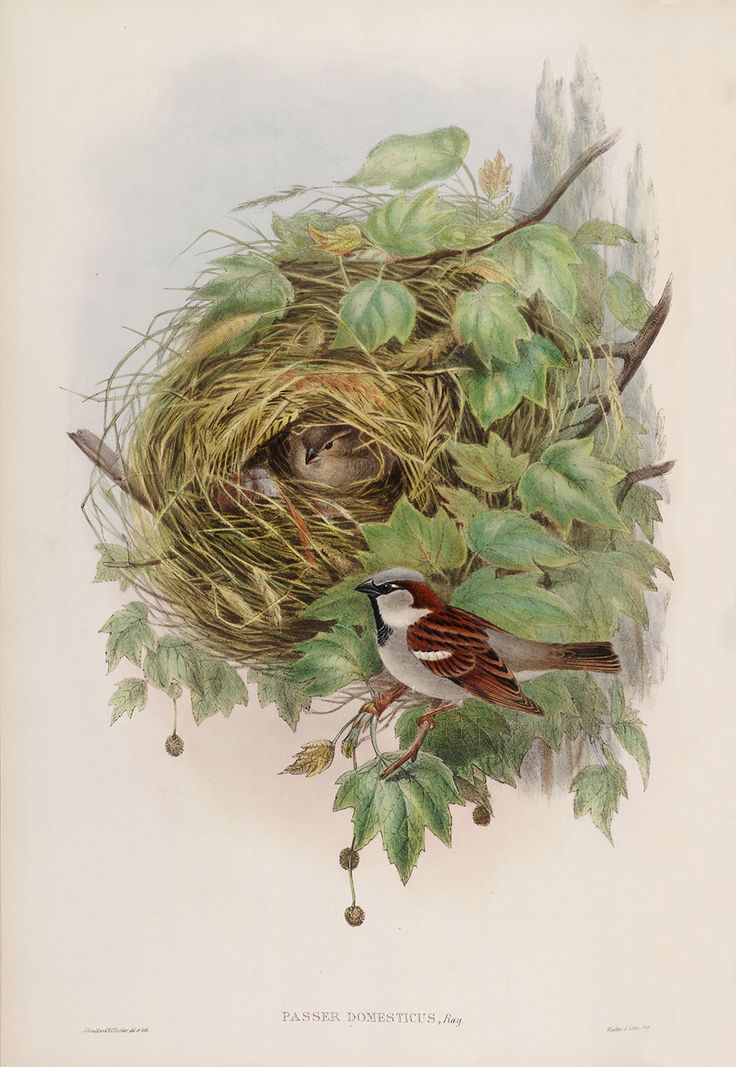

When I visited England at the beginning of last month, the English House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) was notable for its scarcity. I spent a week in London, Sheffield and the Peak District and only once heard the familiar and once ubiquitous jib-jib (see recent post) in a small park near St Pancras International in central London. Just as well that we don’t call it the ‘English’ Sparrow anymore. Actually they have far from disappeared from the English landscape but their population size did drop by about half from the 1970s to the 1990s, having more-or-less stabilized at present-day numbers by the turn of the millennium.

The precipitous decline in House Sparrow populations in the UK has been well-documented but the causes are thought to be complex—changes in farming practices reducing food availability, competition with other birds, loss of nest sites in cities. and the usual problems with pesticides. Once considered a pest, this species is now of conservation concern in the UK and Europe. North American Breeding Bird Survey data also show a similar decline in numbers from 1966-2004 with a loss of about 2% per year continent-wide.

Because it was so common and readily breeds in nest boxes, the House Sparrow became a model bird species for studies in behaviour and ecology in the latter half of the 20th century, along with species like the Zebra Finch, Rock Pigeon, Red-winged Blackbird, Great Tit, Blue Tit, and Pied Flycatcher. Because it was introduced to North America in the 1850s and spread rapidly across the continent, the House Sparrow was/is considered to be a pest and is not protected by the Migratory Birds Convention Act. This may be one reason that large collections of this bird were possible in the 1960s and 70s for the purpose of looking for morphological evolution (adaptation and drift) across the continent, among other things. The species is still common enough to be the focus of several exciting research programs in both North America and Europe, and has been the subject of more than 5000 papers, at least two ‘recent’ science-based books, and an AOU Ornithological Monograph.

A new paper by Matthew Holmes in the Journal of the History of Biology documents an interesting and largely forgotten period of debate about the House Sparrow in the UK in the late 1800s, one that ushered in a new research discipline called ‘Economic Ornithology’: “Economic ornithology would examine the economic impact of birds on agriculture, a topic neglected by ‘‘recognized text-books on ornithology’’ which only provided readers with ‘‘vague and agriculturally useless statements’’ (Cathcart, 1892).

The debate centred around the sparrow’s influence on agricultural with one side claiming disaster and the other that the bird was at worst harmless, at best beneficial because it consumed insect pests. Thousands of sparrows were slaughtered in the late 1800s both in a vain attempt at control and to collect data on the sparrow’s diet. The House Sparrow, like all good pests, was oblivious to these control attempts and continued to thrive despite widespread concern: “Local meetings of agricultural societies and so-called ‘‘sparrow clubs’’ uniformly condemned sparrows’ consumption of crops. Once labelled as ‘‘vermin,’’ non-productive species were freely persecuted in the fields of Victorian Britain…” A farmer, Charles Newman, encapsulated the attitudes of the day in 1861: “No doubt many persons are opposed to their [sparrows’] destruction, considering that this feathered race were created for some wise purpose. Such was undoubtedly the case in the original order. But the Great Creator made man to rule over the fowls of the air and the beasts of the field, leaving it to his judgment to destroy such that were found more destructive than beneficial.”

In this new paper, Holmes argues that “Nineteenth-century naturalists of all stripes were driven by an overarching sense of purpose, or participation in a grand intellectual endeavour. Acquiring and systematising knowledge gleaned from study of the natural world was associated with moral, religious and social wellbeing.” By the early 20th century this kind of ‘natural history’ had given way to economic ornithology and a general shift to evidence-based science. By the beginning of the 21st century ‘natural history’ was firmly grounded in evidence such that most field biologists are now proud to call themselves natural historians.

Sources

Anderson TR (2006) Biology of the Ubiquitous House Sparrow: from genes to populations. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Cathcart AF (1892) ‘Agriculturally economic ornithology.’ The Times, 16 May.

Holmes M (2017) The sparrow question: social and scientific accord in Britain, 1850–1900. Journal of the History of Biology 50:645-671

Kendeigh SC, ed. (1973) A Symposium on the House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) and European Tree Sparrow (P. montanus) in North America. Ornithological Monograph No. 14

Summers-Smith JD (1963) The House Sparrow. Collins New Naturalist Series Monograph No.19, London

hiya bob..yes there is a decline in the humble house sparrow in England.however, I have a an allotment and we have a steady flock of about 40-50 birds that thrive here.the birds are fed on a regular basis during the winter.in summer the birds are left to fend for themselves because plenty of insects are abundant at this time of year..you take care …