When I was a young teenager I spent my Saturday mornings during the school year at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM). I was there to attend the weekly meeting of the Toronto Junior Field Naturalists’ Club, but often stayed afterward to explore the public galleries. I particularly loved the dioramas of birds and mammals as they took me to distant places and bygone times that I could only dream or read about. In those days, there were virtually no nature documentaries on TV and precious few in the theatres [1].

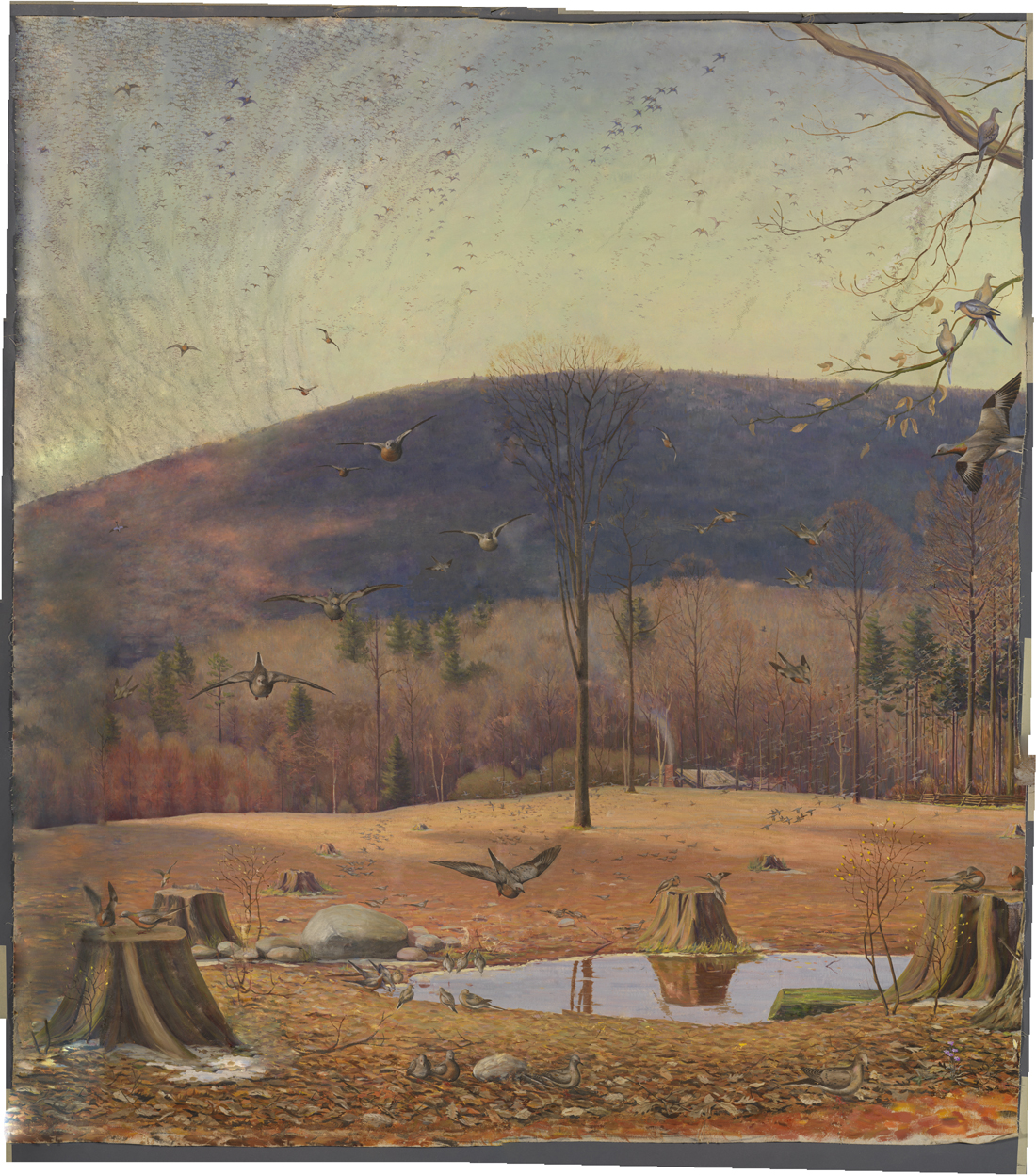

Of all those superb dioramas, my favourite was the Passenger Pigeon, showing immense flocks (painted) descending into a forest clearing scattered with pigeons (mounted specimens) foraging on the acorns:

The scene reproduced depicts an April morning in the 1860s near Forks of Credit, Ontario…The visitor inspecting the exhibit should imagine himself standing at the edge of an old beech-maple forest overlooking the pioneer’s clearing. The scene is as we might have found it in the 1860s. The great pigeon flight is underway and will perhaps continue throughout the day. [2]

That diorama was opened to the public in 1935, the brainchild of Lester L. Snyder, the curator of birds, and constructed and painted by E. B. S. Logier who had joined the museum as illustrator in 1915. My memories of those dioramas came flooding back a couple of weeks ago when I saw the names Mark Peck and Allan Baker [3]—both from the ROM—among the authors of a new paper out of Berth Shapiro’s lab (UC Santa Cruz) on Passenger Pigeons published in Science, but more on that in a minute.

Standing in front of that diorama I can remember thinking that a bird that had once been that abundant could not possibly be extinct. After all, Peterson’s Field Guide still illustrated them (in a head and shoulders vignette on p 181 of my copy) so maybe he thought the bird might still be seen. My teen birding buddies and I spent many an afternoon naively scouring flocks of Mourning Doves just in case. After all, bison were also once extremely abundant, and hunted relentlessly, but were still round, albeit in small numbers.

I was also heartened by the fact that even if the species was really extinct, there must be thousands of specimens in museum collections that could be used for further study, since the ROM alone appeared to have so many that they could fill a diorama with mounted specimens alone. When I mentioned this to my friend and mentor Jim Baillie, assistant curator of birds at the ROM, he just laughed and told me there were only about 1500 specimens worldwide, of a species that once numbered in the billions. The reason for this wealth of specimens at the ROM, he said, was that they had been the beneficiaries of what he considered to be a major coup, when a local naturalist, musician and businessman [4], Paul Hahn, had decided—shortly after the Passenger Pigeon went extinct in 1914—to donate to the ROM as many specimens as he could locate, as a way “to ensure that future generations would know at least how handsome a bird it was.” [5]

Hahn was born in Germany in 1875 but moved to Toronto with his family in 1898. In 1902 he saw his first Passenger Pigeon, a mounted specimen in a farmhouse north of the city and decided then to “set about gathering as many as possible of the mounted birds scattered around the country, both for the sake of future students and with the intention of preserving at least some specimens of a bird that would probably soon be extinct.” [5]. He presented his first specimen to the ROM in 1918 and had donated 70 by the time he died in 1962.

As a result of Hahn’s generosity, the ROM had 124 Passenger Pigeon skins and mounts by 1962, more than any other collection worldwide. I know this because in 1957 Mr Hahn started compiling a list of all the specimens of 7 extinct (our nearly so) bird species [6] held in museums and private collections around the world. Hahn died before his list could be published but Baillie took up the task, seeing it through to print in 1963 as a book Where is that Vanished Bird? That book lists every specimen (including skeletons) known to Hahn [7], its date and place of collection, its sex, the collector, and the current collection in which it was held.

The first Passenger Pigeon specimen whose collection date was known was a male taken in the Carolinas in about 1810, housed with one other specimen (a female, from Georgia collected in 1821) in the Zooligische Museum in Berlin. The Naumann Museum in Köthen that Tim Birkhead wrote about last week also had a male, collected in about 1830 (locality unknown).

The recent Science paper made good use of the ROM collection of Passenger Pigeons, analyzing the DNA extracted from the toe pads of 84 specimens, 63 of which were from the ROM. Analyzing both nuclear and mitochondrial genes, the researchers confirmed that the Passenger Pigeon had surprisingly low genetic diversity. This low diversity is unexpected because large populations are predicted from theory to be genetically diverse, and you don’t get larger bird populations than those of the Passenger Pigeon. To explain this loss of diversity, the authors argued that it was driven by high rates of dispersal and adaptive evolution that removed harmful mutations. Such low diversity would have made the species particularly susceptible to disease or environmental change, two factors that might have doomed the species once populations had been decimated by hunting. This study also concluded, based on some sophisticated genomic analyses, that Passenger Pigeon populations had probably persisted at extremely high numbers for 20,00 years or more before the 1800s [8].

The Passenger Pigeon diorama at the ROM was dismantled in 1981, in part because it was showing its age, but also because the age of dioramas was over, replaced in part by the ubiquitous nature shows in TV. That saddens me but I am more than ever convinced that clubs for young field naturalists, and museums that store and preserve specimens, deserve our unending support.

SOURCES

-

Hahn P (1963) Where is that Vanished Bird? Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

-

Hung C-M, Shaner P-JL, Zink RM, Liu W-C, Chu T-C, Hiuang W-S et al. (2014) Drastic population fluctuations explain the rapid extinction of the passenger pigeon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Scienes USA 111:10636–10641.

-

Murray GGR, Soares AER, Novac BJ, Schaefer NK, Cahill JA, Baker AJ et al. (2017) Natural selection shaped the rise and fall of passenger pigeon genomic diversity. Science 358:951–954.

FOOTNOTES

1. The first nature documentaries on TV were a series called Fur and Feathers on Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) channel in 1955-56, in black and white (of course). By 1960, Disney had produced 14 movies in its True-Life Adventures series, including the The Living Desert, The Secrets of Life, African Lion, and White Wilderness all of which enthralled my naturalist friends and I when they played at our local theatre.

2. Text from the ROM’s Passenger Pigeon diorama, courtesy Mark Peck, 22 Nov 2017.

3. Mark Peck is Ornithology Technician at the ROM, where Allan Baker (1943-2014) worked for 42 years as both a curator of birds and eventually head of their Department of Natural History.

4. Hahn was an accomplished cellist who played with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. He also founded Paul Hahn Pianos in Toronto in 1913, a company that is still in business today.

5. Quotations from Hahn 1963:1.

6. As of 1962: skins and mounts of 1532 Passenger Pigeons, 365 Eskimo Curlews, 78 Great Auks, 720 Carolina Parakeets, 413 Ivory-billed Woodpeckers, 54 Labrador Ducks and 309 Whooping Cranes (Hahn 1963).

7. Beginning in 1957 he sent out questionnaires to people and museums that he thought might know or know about those specimens. He got more than 1000 response.

8. Based on DNA samples from only 3 Passenger Pigeons, Hung et al. (2014) performed a different genomic analysis and concluded that population sizes had fluctuated dramatically—only occasionally reaching numbers in the billions—thereby increasing its risk of extinction during population lows. Evaluating the conclusions of these two studies is above my pay grade but I expect that both labs will argue that their analyses are correct.

IMAGES: ROM photos by Brian Boyle, courtesy of Mark Peck (both at the ROM); Paul Hahn from the Paul Hahn & Co. website at https://paulhahn.com/about/who-we-are/

This is my favorite blog. I love natural history and ornithology