CELEBRATING

THE HISTORY OF WOMEN IN ORNITHOLOGY

This month—March 2019—is Women’s History Month in the USA, Australia, and the UK [1]. As President Jimmy Carter said in 1980: “Too often the women were unsung and sometimes their contributions went unnoticed” [2].

For a few years now, I have been compiling information on the history of women in ornithology because their contributions do not seem to have been well documented. Sure, there are big names that most ornithologists are aware of—Margaret Morse Nice, Rachel Carson, Harriet Lawrence Hemenway and Minna Hall—but there are many more who are not nearly as well known as their male contemporaries even though they contributed just as much to the field.

To celebrate the historical role of women in ornithology, I will highlight this month the accomplishments of some lesser known women ornithologists, as well as in June in a couple of displays at the AOS conference in Anchorage. As a student of the history of ornithology, I am often reminded about how little I know about the historical role of women in our field. Hardly a month goes by when I do not hear of another great woman ornithologist from the past who made notable contributions but who I had not previously been aware of.

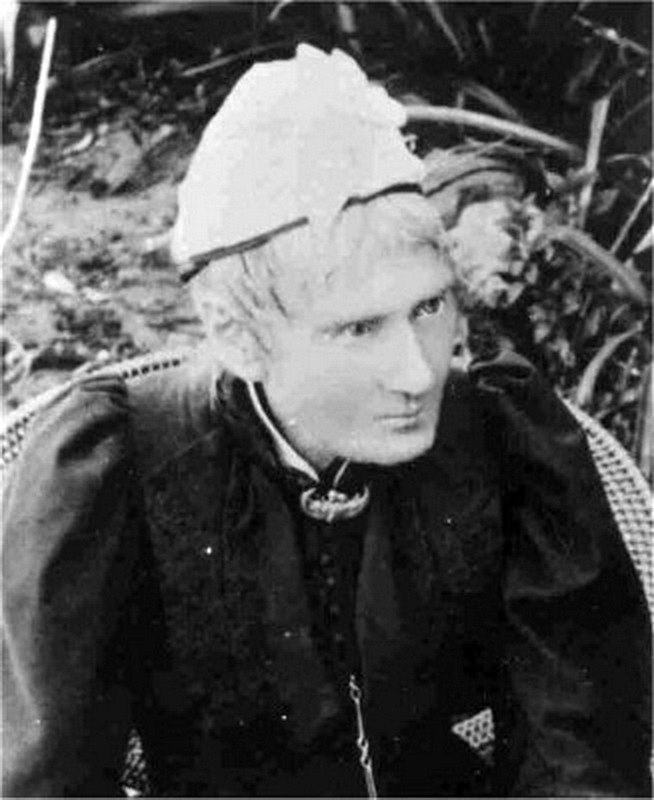

For the first post this month, I am going to focus briefly here on a woman that I expect will be unknown to most readers. Certainly none of the dozen or so North American colleagues that I asked had ever heard of her despite the facts that (i) she was well known in her day (1800s), (ii) she wrote and thought exceptionally well, (iii) she made significant contributions to the study of birds in South Africa, and (iv) she fully understood and appreciated the ideas published by Darwin and Wallace. In her knowledge and appreciation of those ideas she was well ahead of most of her male colleagues. She also had a no-nonsense approach to the various impediments encountered by women in science in the Victorian era. Her name is Mary Elizabeth Barber.

Barber was brought to my attention by a 2015 paper by Tanja Hammel in Kronos, a journal of history and the humanities in South Africa. Hammel is in the History Department at the University of Basel, where she did her PhD on Barber. Hammel writes with unusual clarity and assesses quite objectively the life of Barber in the context of life in the Victorian era and particularly the ‘micro-politics’ in South Africa in those days. She argues that Barber ‘cultivated a feminist Darwinism‘ using the evidence of female choice in birds to inform her own quest for gender equality among the naturalists of the day. She also argues well that Barber’s personal experiences shaped her approach to bird study, as it undoubtedly does for all of us.

Hammel also does a very clear-headed job of criticizing the recent approach to ‘gender essentialist studies’ that claim that there are ‘distinctly female traditions in science and nature writing’. She argues, for example, that men and women did the same sort of research as ornithologists, using the same methods, and often used birds as examples to ‘debunk Victorian gender roles’.

Mary Barber (née Mary Bowker) was born in England in 1818, but her family moved to South Africa when she was only four, and she spent the rest of her life there. She apparently taught herself to read and write, and began at an early age studying the local plants. By the age of 30, she was already a well-regarded botanist and botanical illustrator, corresponding with and providing both specimens and information to the leading botanists of the day [3].

As her botanical work progressed Barber became increasingly interested in the insects that fed on the plants she studied, then on the birds that fed on those insects. Edgar Leopold Layard acknowledged Barber’s ornithological contributions in his Birds of South Africa published in 1867, the only woman he mentioned. As an ornithologist, she was a collector, an illustrator, and a keen observer, often spending days in the field.

In 1878, she published a remarkably modern assessment of bird colouration in response to the debate between Darwin and Wallace on the influence of female choice on extravagant male plumage colours. She clearly supports Darwin’s side of the argument when she says that “it is comparatively as easy task to follow in his footsteps, and to spell out the book of nature with Mr. Darwin’s alphabet in our hands” [4]. In her writings, she interpreted much of what she observed in light of Darwin’s and Wallace’s recent theories.

Barber corresponded with Darwin after she was introduced to him (presumably by mail) by a fellow (male) entomologist in 1863. Both Darwin (in his books on Emotions and Orchids) and Wallace (in Darwinism) refer to her observations and insights. Barber, however, was infuriated with Wallace for attributing some of her observations to the English entomologist Josiah Obadiah Wedgwood [5]. She was particularly sensitive at the time because an article she had written with her brother, James Bowker, had been given to Layard before a trip he made to England and ended up being published by a ‘Mr Layland’.

Despite these slights [6], and a difficult marriage, Barber was an energetic and enthusiastic naturalist and her writing expresses complete confidence. In part, I suspect, to establish her credentials as a serious scientist, she never referred to birds by their common (English) names, arguing that ‘barbarous names‘ should be ‘avoided by all means‘. That very ‘scientific’ approach, her broad network of correspondents, and her ideas about gender equality made her very much like a twenty-first century ornithologist, not at all fitting the common image of the Victorian woman who lived like a bird in a gilded cage.

SOURCES

- Barber ME (1878) On the peculiar colours of animals in relation to habits of life. Transactions of the South African Philosophical Society 4: 27-45

- Darwin CR (1872) The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London: John Murray.

- Darwin CR (1877) The various contrivances by which orchids are fertilised by insects. London: John Murray

- Hammel T (2015) Thinking with birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber’s advocacy for gender equality in ornithology. Kronos 41: 85-111.

- Layard EL (1867) The Birds of South Africa : a descriptive catalogue of all the known species occurring south of the 28th parallel of south latitude. Cape Town: Juta

- Siegfreid R (2016) Levaillant’s Legacy – A History of South African Ornithology. Noordhoek, Western Cape: Print Matters Heritage.

- Wallace AR (1889) Darwinism: an exposition of the theory of natural selection with some of its applications. London & New York: Macmillan & Co.

Footnotes

- March is Women’s History Month: but not in Canada, when it’s October

- quotation from Jimmy Carter: when he designated National Women’s History Week.

- botanists of the day: for example, she corresponded often with Joseph Dalton Hooker, director of the Botanical Gardens at Kew in England and probably Darwin’s closest friend.

- quotation about Darwin: from Barber 1878 page 27

- Josiah Obadiah Wedgwood : not the father of Darwin’s wife Emma, but possibly a relative.

- these slights: she seems to continue to be ignored as she is not even mentioned in Siegfried’s recent history of South African ornithology

Wow! Interesting. I suppose she was less known because of being in South Africa? I would love to know more of her specific ideas. It is also interesting that she managed to do so much research with three children, something you, perhaps wisely, don’t mention. Research takes time and family responsibilities with an absence of support also take time. I wonder if there were little pockets of research active women or if these women just popped up in a desert of female scientists and prevailed on their own. What was the social fabric that best let women succeed in discovery back then and what can we learn from it?