For at least 400 years, ornithologists—and presumably naturalists of every stripe—have kept notebooks recording each day’s observations from the field. In 17th century England, these were called ‘Commonplace Books’, rather large bound volumes that were used by scholars to record ideas, notes about what they read, experiences and observations. This was the Renaissance, and the beginning of the scientific revolution, where scholars were questioning everything, and basing conclusions on direct observations rather than hearsay, ancient texts, and idle speculation.

John Ray and Francis Willughby [1] each had their own Commonplace Book, as required by their tutors at Cambridge. In the late 1600s, the great English philosopher John Locke considered Commonplace Books to be so important to the progress of science that he published a scheme for properly indexing a commonplace book in an addendum to his influential An Essay Concerning Human Understanding [2]. And in the 18th century, Linnaeus used his Commonplace Book to record and develop his ideas about his binomial system of nomenclature, resulting in his Systema Naturae [3].

Commonplace books seemed to be de rigueur for scientists and scholars through the 1800s eventually evolving into the specialized (rather than all-encompassing) small notebooks (e.g. Moleskins) and field notebooks (e.g. Rite in the Rain) used by writers and naturalists, respectively, throughout the 20th century.

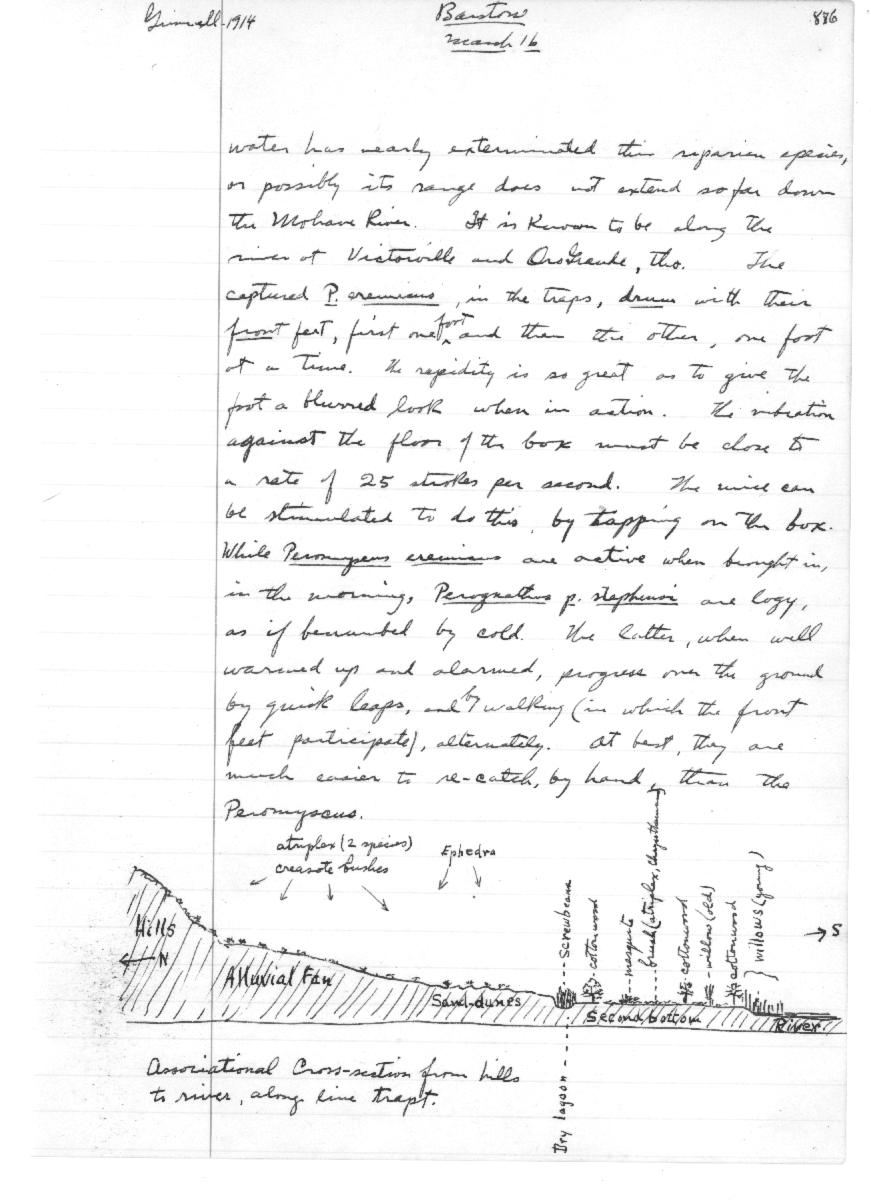

In the early 1900s, the American ornithologist Joseph Grinnell thought that field notebooks were so important that he developed a systematic method of note-keeping that he taught all of his students and colleagues. His method, sometimes called the Grinnell System, involves at least two different books—the Field Notebook, carried everywhere to record observations immediately, and the Field Journal, to daily record experiences and observations as in a diary, using the Field Notebook. Each diary-like entry in the Field Journal is written in the evening, using the Field Notebook for details. The Field Journals, or separate notebooks, also include Species Accounts compiled during the course of a field trip, and a Catalog, recording the details of all specimens collected. The method seems simple enough but requires some discipline to maintain during busy field work. Grinnell even went so far as to recommend the sort of paper and ink needed to make the method historically valuable: The India ink and paper of permanent quality will mean that our notes will be accessible 200 years from now….we are in the newest part of the new world where the population will be immense in fifty years at most. [4]

I am an academic descendant of Grinnell [5] and while I am not a very disciplined diarist, I treasure the 57 notebooks that I have used to chronicle my field activities over the years. These books contain some data but they are mostly a summary of where I went, what I did, what the weather was like, who my companions were, what I found interesting each day in the field, and ideas for further work. My field data sheets and recordings occupy another 5 metres of book shelf and a few terabytes of hard drive space.

In 1908, Grinnell was appointed as the first director of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at Berkeley, where he set out to build a collection of birds and mammals from California. To do that he embarked on a series of expeditions to the Colorado Desert (1908), The Colorado River (1910), Mount Whitney (1911), the San Jacinto Mountains (1913), the Sierra Nevada (191–1920), and Lassen Peak (1924-1929).

Grinnell kept such careful field notes that the MVZ scientists decided to survey some of those same areas beginning in 2002, to see what, if anything, had changed over the past century. They called this the Grinnell Resurvey Project. Grinnell did not actually conduct censuses using repeatable, modern-day methods, but he did provide enough information that reasonable comparisons could be made.

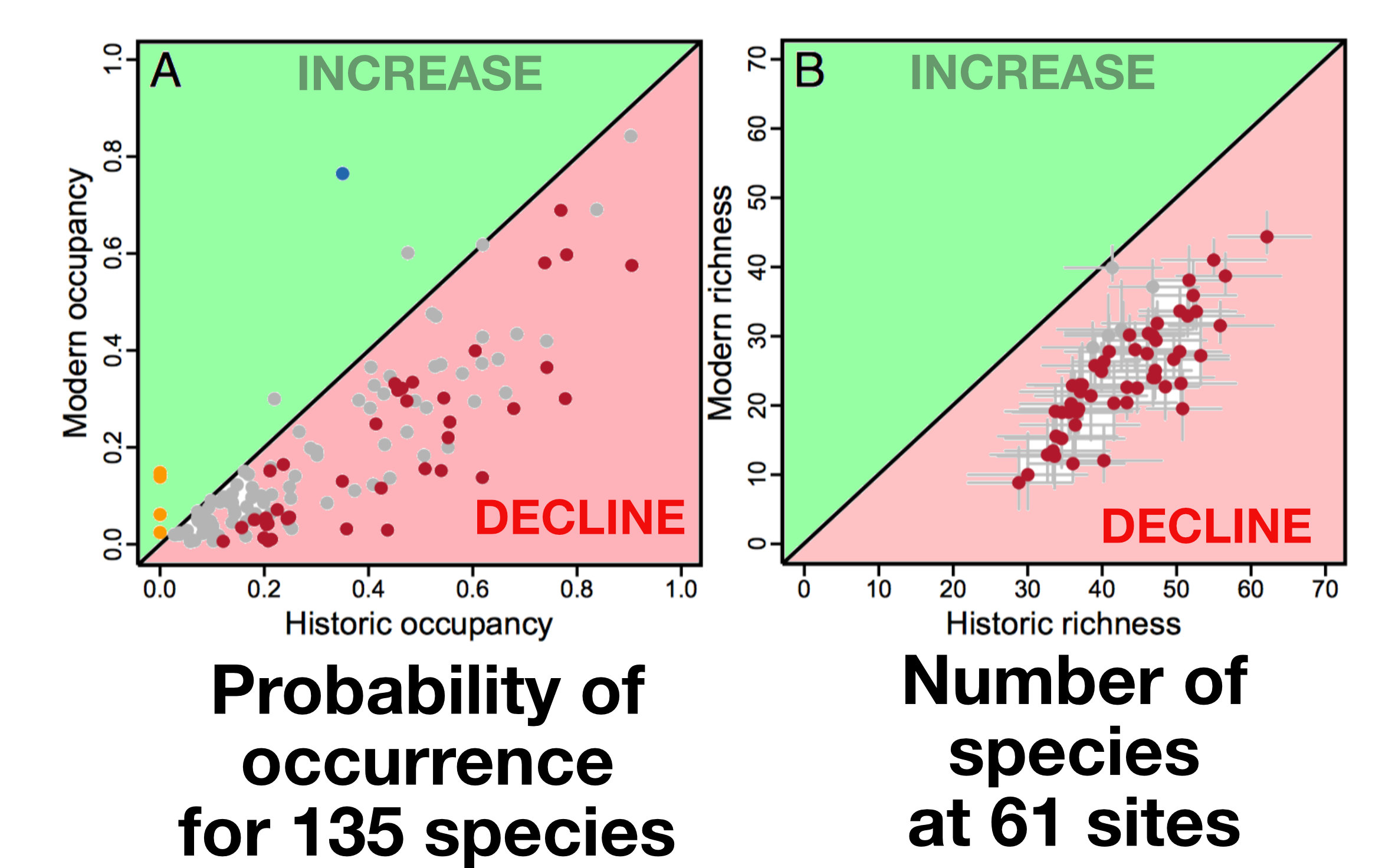

Earlier this month, PhD student Kelly Iknayan and AOS Past President Steve Beissinger published a paper in PNAS using both Grinnell’s surveys and the recently completed replication to analyze the changes in bird fauna in the Mojave Desert of California. The nice thing about this resurvey is that most of the sites visited by Grinnell in the Mojave are on federal lands, with little or no anthropogenic influence in the intervening 100 years. The results are clear…and depressing.

Surveying 61 of the same sites studied by Grinnell, they found that the number of bird species at each site had declined, often significantly (red dots of figure below). And the number of sites where they found different birds had also declined for >125 of those 135 species. Only the Raven was found at significantly more sites a century later (blue dot, below).

By evaluating several potential causes for these changes, Iknayan and Beissinger found that climate change was the strongest predictor, particularly with respect to increasing drought conditions. As they point out, in their paper’s abstract: Climate change has caused deserts, already defined by climatic extremes, to warm and dry more rapidly than other ecoregions in the contiguous United States over the last 50 years. Desert birds persist near the edge of their physiological limits, and climate change could cause lethal dehydration and hyperthermia, leading to decline or extirpation of some species. [6]

I expect that Iknayan and Beissinger take better field notes that I do, especially as they are both also academic descendants of Grinnell [5] and work in his shadow at Berkeley. But even the best field biologists’ note-taking abilities are rapidly becoming anachronisms, I fear, with the advent of eBird, automated recording devices, and digital database apps. I think this is sad, not because I long for the good old days—I am quite tech savvy—but because those detailed field journals are an important historical record [7] that show both the human side of field work and the nuances associated with collecting data.

You could argue that Grinnell’s field surveys would have been more useful today if he had digitized his records and taken more quantitative measures, and you would be right to some extent. But field naturalists a century from now will no doubt lament the passing of the commonplace book and the Grinellian field notebook when they try to understand our quantitive, digitized, data stored faithfully in online repositories if those data are not also supplemented by a little personalized narrative.

SOURCES

-

Charmantier I (2011) Carl Linnaeus and the visual representation of nature. HIST STUD NAT SCI 41:365–404.

-

Iknayan KJ, Beissinger SR (2018) Collapse of a desert bird community over the past century driven by climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 201805123.

-

Locke J (1689) An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. London: The Buffet.

-

Linné CV (1766) Caroli a Linné. Systema naturae : per regna tria natura, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis / (t.1, pt. 1 (Regnum animale) (1766)). Holmiae :Impensis direct. Laurentii Salvii.

Footnotes

- Ray and Willughby: see previous posts here, here, here, and here

- An Essay Concerning Human Understanding: see Locke (1690) available here

- Sytema Naturae: see von Linné (1766)

- Grinnell on paper and ink: cited from Wikipedia article on Grinnell, here

- Academic descendants: me through Peter Grant to Ian McTaggart-Cowan to Grinnell; Beissinger through Bobbi Low to Frank Blair to Lee Dice to Grinnell (see here and here for details)

- Quotation about climate change: from Iknayan and Beissinger 2018, abstract

- Important historical record: see here for example

IMAGES: Linnaeus’s notebook from Charmantier (2011); Grinnell’s notebook from the Grinnell ECOREADER; graphs modified from Iknayan and Beissinger (2018)