Guest post by researcher Dan Ruthrauff

Linked paper: Flexible timing of annual movements across consistently used sites by Marbled Godwits breeding in Alaska by D.R. Ruthrauff, T.L. Tibbitts, and R.E. Gill, Jr, The Auk: Ornithological Advances 136:1, January 2019.

Marbled Godwits are common and conspicuous North American shorebirds. On its prairie breeding grounds, the godwit’s raucous call and proud flight display alerts all to its presence, and the species is equally obvious on its temperate nonbreeding grounds along both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts due to its gregarious nature and telltale alarm call. So how did such a charismatic species go largely undetected in Alaska until the 1980s?

The reason lies in this unique subspecies’ far-flung breeding range and cryptic occurrence across the state. Dan Gibson and Brina Kessel first described the Alaska-breeding subspecies Limosa fedoa beringiae in a 1989 research paper in The Condor. The authors pieced together information from anecdotal observations and a handful of specimens collected at a remote site on the Alaska Peninsula and combined this with evidence from museum specimens to define the subspecies, broadly describe its range, and ponder its migratory movements.

Fast forward thirty years, and we’ve learned surprisingly little about this subspecies, which is believed to number only about 2,000 individuals. Dan and Brina’s publication served as a touchstone for subsequent research on the subspecies, most of which has focused on the region surrounding Ugashik Bay on the Alaska Peninsula. Accessible only by plane or boat, this region has fewer than 200 human inhabitants across an area about half the size of Connecticut, a fact that helps explain why this brightly colored, boisterous shorebird was ”unknown” to science for so long. In 1992, researchers working near this site found the first nest of the species in Alaska—a hatched nest, with eggshells that helped identify it as that of a godwit. The first active nest of the subspecies was not documented until 2008, discovered by a U.S. Geological Survey crew conducting an inventory of breeding birds in nearby Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve. Around this same time, biologists at the Alaska Peninsula National Wildlife Refuge were also conducting systematic inventories across large portions of the Alaska Peninsula. Their work slowly painted a picture of the species’ range and habitat preferences in the region.

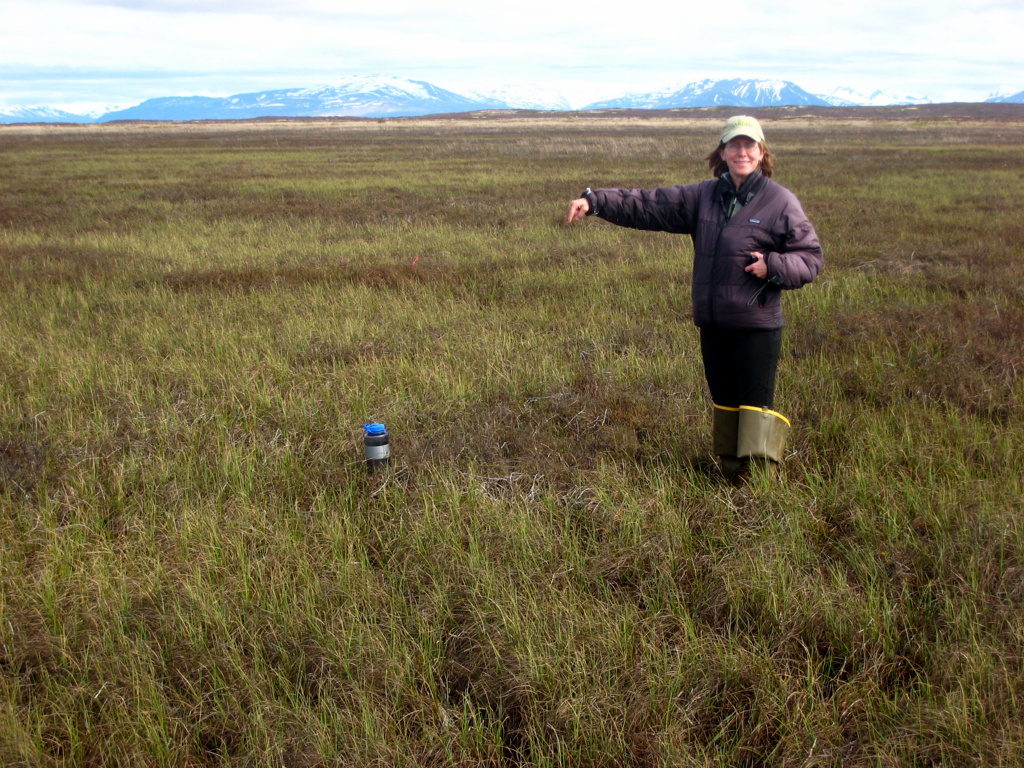

These efforts culminated in 2006 and 2007 when Bob Gill, Lee Tibbitts, and I conducted systematic helicopter-based surveys to determine the breeding range of the subspecies in Alaska. Limited mostly to moist lowland meadows, the breeding range of the species in Alaska ranges from just south of Egegik Bay in the north to about Port Heiden in the south, a span of only about 150 km. Thus, the subspecies’ breeding range is small and remote and, curiously, is separated from the next nearest Marbled Godwit breeding location by about 2,500 km. We also trapped and equipped nine Marbled Godwits with solar-powered satellite transmitters; given the near-complete lack of information regarding the subspecies in general, we really did not know what to expect as these birds began their migratory movements.

To our pleasant surprise, we ended up tracking these birds for a long time; the last individual’s transmitter stopped functioning in October 2015. Not only did we learn a great deal about the basic migration ecology of this subspecies—much of which simply confirmed Dan and Brina’s original hypotheses based on deductive reasoning and critical thinking—but these migratory tracks also presented us with a unique opportunity to assess the degree to which individual Marbled Godwits were consistent in the timing of their migrations and their use of sites throughout their annual cycle.

Like many of their relatives, Marbled Godwits that breed in Alaska are homebodies, displaying a predictable attachment to a handful of sites. In contrast to globetrotting Bar-tailed and Hudsonian godwits, however, Alaska’s Marbled Godwits are highly flexible in the timing of their movements. It appears that the subspecies’ relatively short migration between its Alaskan breeding grounds and nonbreeding locations along the Pacific Coast of Washington, Oregon, and California affords these birds more opportunity to adjust the timing of their annual movements. The factors driving this flexibility ultimately remain a mystery—but this seems appropriate for a species that has hidden in plain sight for so long.