John Gould’s A Synopsis of the Birds of Australia, and the Adjacent Islands strikes me as the oddest of the superbly illustrated 19th-century bird books. Published by subscription that began in 1837, it was illustrated by his wife, Elizabeth, but only shows in colour the head of each species [1], unlike any of the other hundred or so ‘Birds of…’ books [2] that I know of. In some cases, she has drawn the feet or wings separately but only as outlines, adding colour in only a couple of instances where it may have been thought to be important for identification. Even Louis Agassiz Fuertes’s album of Abyssinian birds [3], which shows the heads of many species, at least has vignettes of the whole bird on most of the plates.

Why did the Goulds decide to paint just the heads of Australian birds? I have three hypotheses, outlined below, but first a little backstory.

John Gould was initially, by trade, a taxidermist, setting up his own practice in London in 1824. Many prominent ornithologists sent him their specimens to mount and he became both very good at his trade and very well-known. In 1827, he was appointed the first Curator and Preserver at the museum of the Zoological Society of London, where he prepared bird specimens sent to the ZSL from the colonies and elsewhere.

Charles Coxen, who called Gould The Birdstuffer, was also a taxidermist and introduced John to his older sister, Elizabeth. John and Elizabeth were married in January 1829, and it was not long before Elizabeth began making drawings and paintings of the birds that John was stuffing for his customers. By 1830, John was already selling some of Elizabeth’s artwork to customers for his taxidermy.

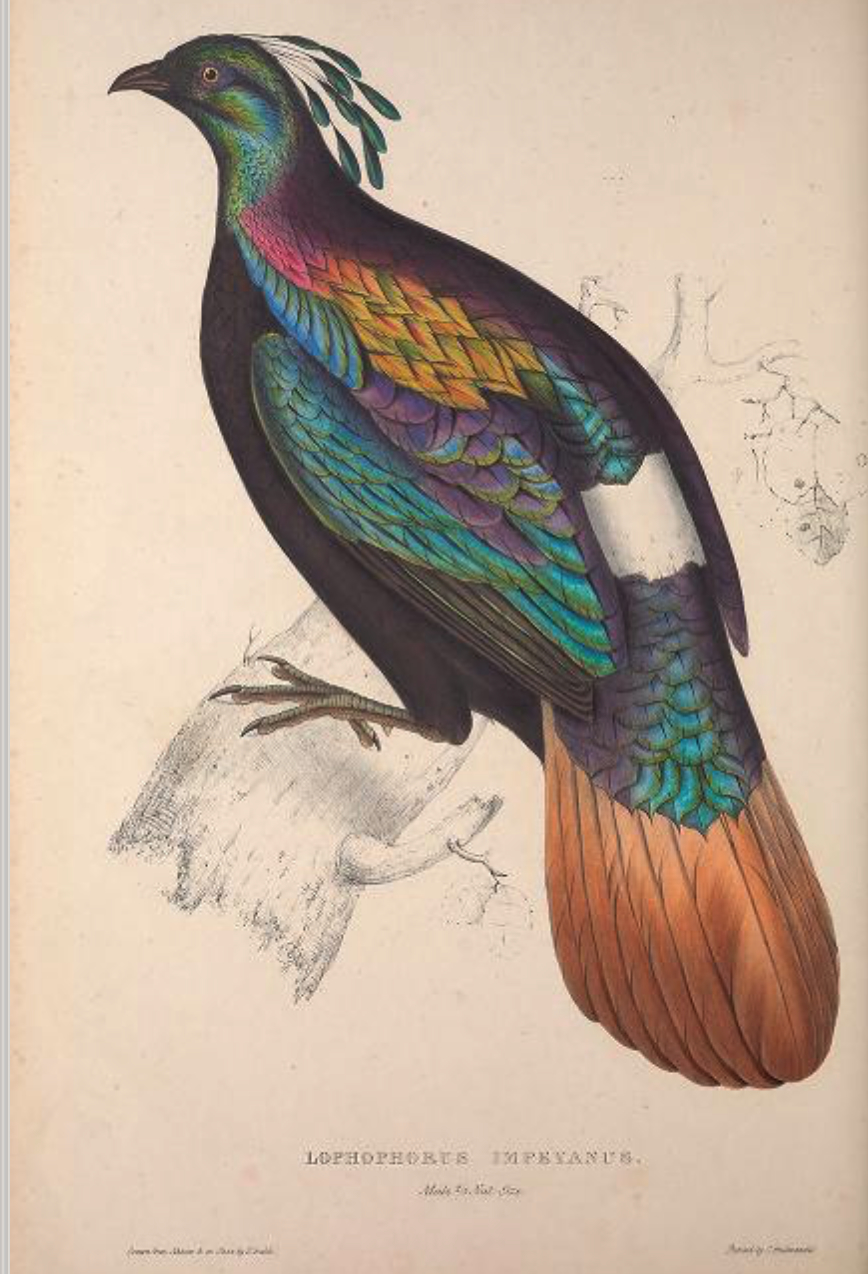

When the ZSL received a shipment of bird specimens from India in 1830, John saw this as an opportunity to use Elizabeth’s artistic skills to produce a book of Himalayan birds, many of which were previously undescribed. He also recognized the potential for lithography to produce much finer illustrations than were possible with woodcuts or copper plates, especially with respect to the nuances of shading and feather detail. To that end he implored Elizabeth to learn lithography, which she quickly mastered. By 1832 Elizabeth had produced 80 hand-coloured lithographs illustrating 100 bird species from the Himalayas, bound together with text to form their first published book [4]. In recognition of her contribution, the systematist for that project named one of the new species as Mrs Gould’s Sunbird (Aethiopygia gouldii).

Elizabeth’s brothers, Stephen (in 1827) and Charles (in 1834), moved to Australia where they established farms in New South Wales, frequently sending back bird specimens for John. As before, John soon realized the value of, and potential interest in, these birds as many had not yet been formally described, nor illustrated. John immediately sought to present these new specimens in a ‘synopsis’ but then to go to Australia with Elizabeth to embark on a full Birds of Australia project, patterned after the Birds of Europe project that he and Elizabeth had just completed in 1837. Gould’s idea for the Synopsis was to publish it in 6-8 parts, with each part comprising 18 plates with descriptions, measurements and affinities of each species, to sell the parts either coloured or uncoloured. They abandoned the project after publishing only four parts and set off for Australia in May 1838.

So why illustrate only the heads in colour?

Hypothesis One: The Goulds had not yet seen Australian birds in the field and were nervous about depicting them in inappropriate poses or habitats. This was my first thought, but that was soon dispelled when I looked at their A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains published in 1831. Here, Elizabeth illustrates in full colour birds she could not have seen alive, even though each of her paintings says ‘Drawn from Nature & on Stone by E. Gould.’ She may have seen some of these birds in zoos or aviaries but I suspect that ‘Drawn from Nature’ simply means that she used the actual bird specimens to inform her painting. Some of her paintings of Himalayan birds—and later of Trogons [5]—do look a little awkward so maybe she did realize that she really needed to see the birds, or at least their close relatives, in nature to make credible paintings of the whole bird.

Hypothesis Two: John Gould knew he was going to visit Australia soon, and wanted to produce a magnificent book on the Birds of Australia, for which ‘his’ Synopsis would be a teaser, driving up subscriptions. Gould was the consummate entrepreneur so this seems highly likely to me. He stopped work on the Synopsis early in 1838 when it was only part way done, presumably because he had enough subscriptions to see that the bigger book would be popular, and his big Australia trip was fast approaching.

Hypothesis Three: The Goulds were in a hurry, and illustrating just the heads would take a lot less time for both the artist and the colourists. As noted above, the Goulds started work on the Synopsis only a couple of years before their planned trip to Australia. Presumably drawing and colouring heads would take less than half the time needed for Elizabeth to draw the entire bird and background, and to colour one copy for the colourists to work from. In 1837, when Elizabeth started work on the illustrations, she had just had her sixth child [6], and completed her illustrations for the Birds of Europe, so she may have been feeling a little pressed for time, to say the least.

Indeed, John was in such a rush to get his Synopsis in the hands of subscribers in Australia in advance of their trip, that he sent fresh copies of the completed parts on the third Beagle Voyage [7] leaving England on 5 July 1837, arriving in Australia in November. On arriving in Australia in September 1838, the Goulds went first to Tasmania (Van Diemen’s Land) where they met and stayed with the governor, Sir John Franklin [8] and his wife, who were among the subscribers to the Birds of Australia project. John Gould seemed never to pass up an opportunity to enlist royalty and the wealthy and powerful to subscribe to his projects, recognizing full well that that would improve sales. Even Elizabeth must have impressed the Franklins as she gave birth to her sixth child—a son who they named Franklin—at Government House on 6 May 1839.

I have not yet read Chisholm’s biography of Elizabeth published in 1944 so there may be information there to inform my speculations. Whatever the reason for this book of bird heads, the illustrations show us Elizabeth Gould at the height of her artistic talents. She was already a gifted artist when she started painting birds for John but she also learned a lot from Edward Lear, who John also employed. For these bird heads, Elizabeth began using whipped egg-white, for example, to provide a reflective surface to the birds’ eyes, giving them a much rounder appearance. Just look at the details of the eye and the feather structure on Elizabeth’s painting of the Square-tailed Kite, below. Elizabeth’s illustrations for the Synopsis are incredibly lifelike, even more so that her work for the Birds of Europe.

Even though Elizabeth Gould is now recognized for her contributions to bird illustration, and to the success of John Gould’s early ornithological enterprises, we may never know how much she really contributed to ornithology for, like most Victorian wives she did not write very much and worked mainly in the service of her family and her husband’s success. Elizabeth bore her eighth child, and third daughter, in August 1841, but died soon after from a uterine infection incurred during childbirth. By then she had already completed 84 magnificent plates for John’s new Birds of Australia, based on their collections and observations there, a lasting testimony to her exceptional skills.

SOURCES

- Anonymous (1837) Bibliographical notices. Magazine of Zoology and Botany 1:571-572

- Anonymous (1881) Memoir of the late John Gould, F.R.S. The Zoologist 5: 109-115

- Chisholm AH (1944) The Story of Elizabeth Gould. Melbourne

- Chisholm AH (1964) Elizabeth Gould: Some “New” Letters. Journal and Proceedings (Royal Australian Historical Society) 49: 321-36.

- Fuertes LA (1930) Album of Abyssinian Birds and Mammals. Special Publication of the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago.

- Gould J (1832-37) The Birds of Europe. 5 vols. London: published by the author.

- Gould J (1835) A Monograph of the Trogonidae, or Family of Trogons. London: published by the author.

- Gould J (1837-38) A Synopsis of the Birds of Australia, and the adjacent islands. London: published by the author.

- Gould J (1840-48) The birds of Australia. 7 vols. London: published by the author.

Footnotes

- head of each species: for a handful of birds, some details of wing or leg plumage are also coloured, to show off features mentioned in the text. The plates of Striated Pardalote and Square-tailed Kite shown here are examples

- ‘Birds of…’ books: see previous post here

-

Bustard from Fuertes (1930 album of Abyssinian birds: see Fuertes (1930), available online here

- their first published book: it is now customary to list Elizabeth as an author on the books she prepared with John, but the title pages of the books listed above do not include her name, so I have not included her as a named author on those citations.

- Trogons: see Gould and Gould (1835), where many of the birds look to me to be in unnatural poses. Elizabeth would surely have seen trogons in zoos and private collections so she does get some of them right, but curiously not all of them. Maybe she did not realize that all of the trogons behave more or less the same way

- sixth child: Elizabeth had eight children in all but only 6 survived so I assume that this sixth child was the fourth to survive.

- third Beagle Voyage: Darwin was on the second Beagle Voyage. The third was captained by John Clements Wickham who was First Lieutenant on the Darwin voyage.

- Sir John Franklin: yes, that Franklin, who had explored the Canadian Arctic in 1819-22 and 1823-27, but then was governor of Tasmania from 1836-43 after marrying his second wife. In 1845 he returned to the Canadian Arctic in search of a Northwest Passage, where he remains to this day

I would like to note that the illustration above labeled by the artist as a Square-tailed Kite although particularly beautiful and accurate is actually Swamp Harrier (Circus approximans).

The Gould’s were truly gifted artists and left a wealth of magnificent artworks that still leave me in wonder.

Some of the specimens published by Gould turned out to be somewhat questionable.

One of them, the giant trogon (Trogon gigas), was actually questioned by Gould himself in ‘A monograph of the Trogonidae’ (1835-38) and completly left out in his second edition. Unfortunately no further details were described.

T.gigas most likely was composed taxidermy.

The question is who declared Trogon gigas as an invalid species and on what grounds was that decision made?