By Jay Pitocchelli, Biology Department, Saint Anselm College

Related paper: Temporal stability in songs across the breeding range of Geothlypis philadelphia (Mourning Warbler) may be due to learning fidelity and transmission biases by Jay Pitocchelli, Adam Albina, Alex R. Bentley, David Guerra, and Mason Youngblood, Ornithology.

We used a long-term database of songs recorded over 36 years from throughout the breeding range of Geothlypis philadelphia (Mourning Warbler) to answer questions about the current and historical patterns of geographic variation in song in this species. Our goals were to describe change versus stability in the pattern of geographic variation, assess potential mechanisms of change, and test for possible acoustic adaptation of song parameters to vegetation of breeding habitat.

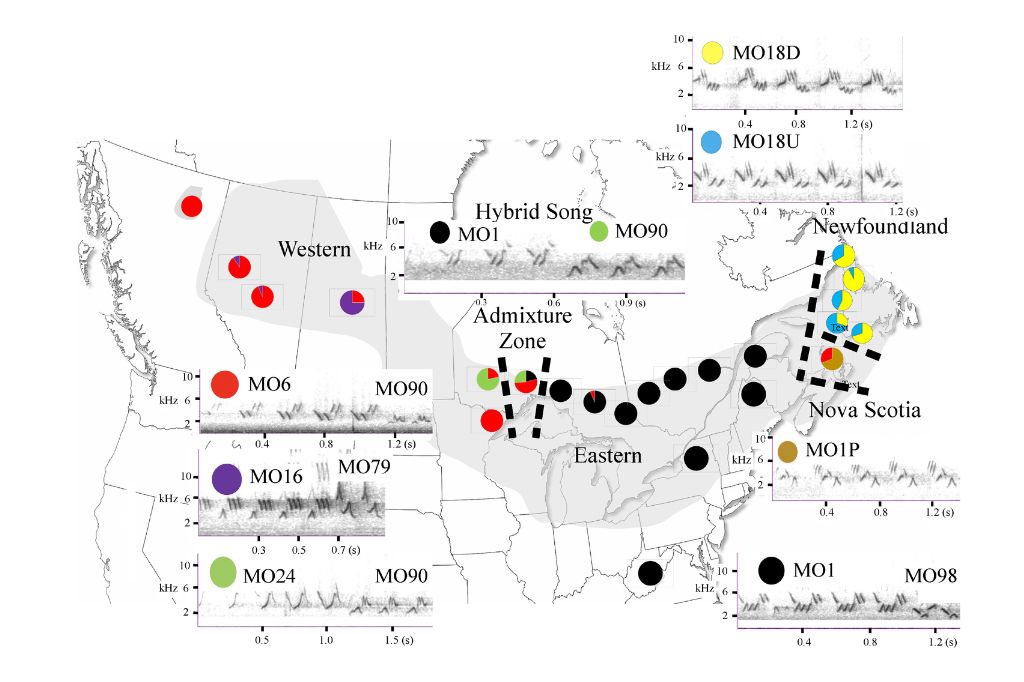

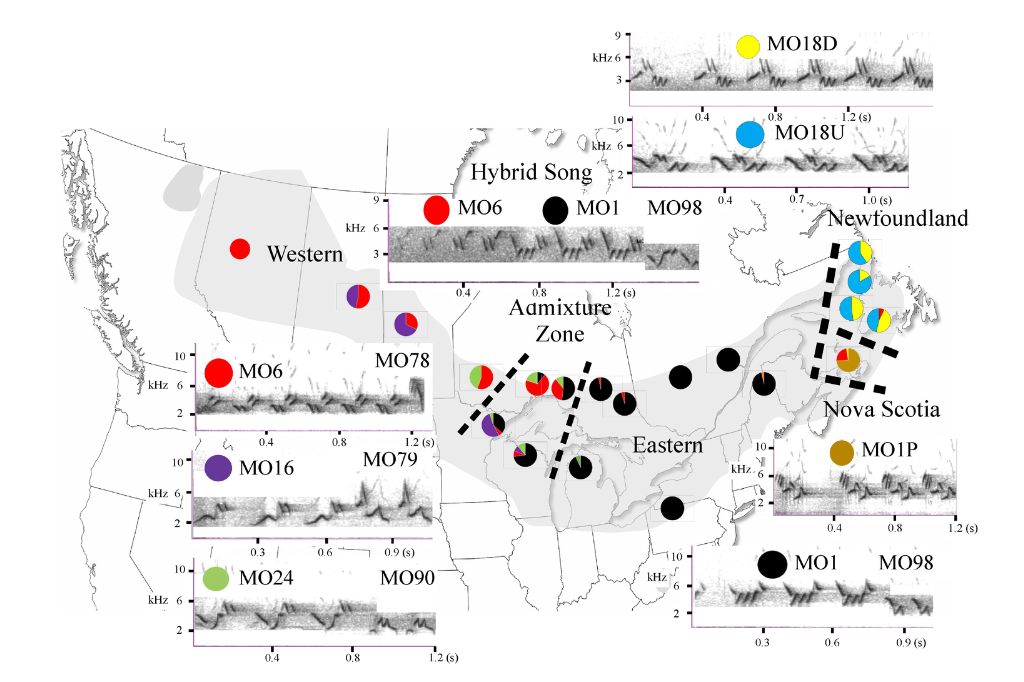

In this paper, lead author Pitocchelli (2011) described four different regional dialects, or regiolects, from the breeding range of G. philadelphia from recordings made in 2005–2009. Each regiolect was characterized by a unique set of song types named after the primary syllable types in the introductory phrase of their songs. A Western regiolect composed of MO6, MO16, MO24 song types extended from northeastern British Columbia, across the Prairie Provinces into central Ontario and the Great Lakes region. An Eastern regiolect with the MO1 song type ranged from central Ontario and the Great Lakes region to the Maritimes and south through the Appalachian Mountains to West Virginia. The Nova Scotia Regiolect with the MO1P song type was limited to Nova Scotia. Newfoundland also had its own regiolect made up of MO18 song types. We found the same pattern of macrogeographic variation existed in historical recordings from 1983–1988 and later recordings in 2017–2019 (Figures 1, 2).

Each regiolect had retained the same song types and syllable types over the 36-year duration of this study. The boundaries between the regiolects were also the same in each time period along with an admixture zone of Western, Eastern, and hybrid songs between the two regiolects in the Great Lakes states and central Ontario. The persistence of the regiolects and their boundaries is notable considering that expansions and contractions in dialect boundaries over time are common (McGregor and Thompson 1988, Harbison et al. 1999).

Birdsong is considered to be transmitted from generation to generation via social learning in Oscine songbirds. Over the course of time, change and divergence may occur among populations resulting in population differences and cultural evolution. Drift or neutral evolution versus natural selection are some potential mechanisms of cultural evolution. Random copying of syllables would be consistent with neutral evolution versus transmission bias which would suggest natural selection. How do you test for these different mechanisms? We developed an agent-based model of birdsong learning within each regiolect to explore whether the observed patterns of song variation among G. philadelphia were consistent with random, unbiased copying versus frequency or content biases that involve selection. Frequency bias occurs when the most common or rarest syllables in a population are favored over other syllables. Content bias happens when a particular syllable—independent of how common or rare it is in the population—is favored. Our agent-based model indicated that selection and content bias were consistent with the observed patterns of variation among the regiolects. The temporal dynamics across the four regiolects are due to strong content bias rather than frequency bias or random, unbiased copying.

The effects of vegetation on sound transmission is also known to drive change and signal divergence in the frequency (kHz) and duration (seconds) parameters of songs among populations (Slabbekorn and Smith 2002). According to the acoustic adaptation hypothesis (AAH), songs with lower frequencies, longer song elements, and slower delivery of repeated elements should occur in closed habitats with dense vegetation. We used high resolution Landsat satellite data as a measure of vegetation density of breeding territories. If transmission of the physical parameters of G. philadelphia songs were affected by habitat characteristics, we should have found songs with lower frequencies, longer song elements, and slower delivery of repeated elements on breeding territories with Landsat variables that indicated dense vegetation. We did not find a relationship between these song parameters and the Landsat data or support for the AAH. Ecological characteristics of the breeding territories did not affect songs or play a role in song divergence among regiolects. Lack of support for the AAH is likely due to selection for the same ephemeral, disturbed, habitat across the breeding range and across the three time periods. Figures 6–8 are examples of similar breeding habitat from each time period near Slave Lake, Alberta.

One major finding of our study is that the macrogeographic pattern of song variation has been stable for 36 years or 12–13 generations. The stability of G. philadelphia regiolects are in contrast to species with rapid turnover in one to five years in dialects like Cacicus cela (Yellow-rumped Caciques, Trainer 1989) or Vidua chalybeate (Village Indigobirds, Payne 1985). G. philadelphia regiolects are more like the longer-term survivorship of dialects of the Molothrus ater (Brown-headed Cowbird, O’Loghlen et al. 2011), Zonotrichia capensis (Rufous-collared Sparrow, Handford 1988), and Zonotrichia leucophrys (White-crowned Sparrow, Harbison et al. 1999). A second conclusion from our study is that the source of variation that may have led to the divergence of unique song types in each of the regiolects is fluctuations in the syllables. Syllable variants were the parts of the song that were in a constant state of flux (e.g., fluctuated, increased, declined, went extinct) versus the physical parameters that remained largely unchanged.