Before Google Scholar and similar search engines, most ornithologists that I know trundled off to the library from time to time to search the current literature on birds. As a graduate student at McGill, I was lucky enough to have the Blacker-Wood Library close at hand and they subscribed to something like 300 bird journals, magazines and newsletters. But even then I often searched through the fat volumes of Zoological Record: Aves, Current Contents, and Biological Abstracts to ferret out papers that might be interesting or relevant to my research.

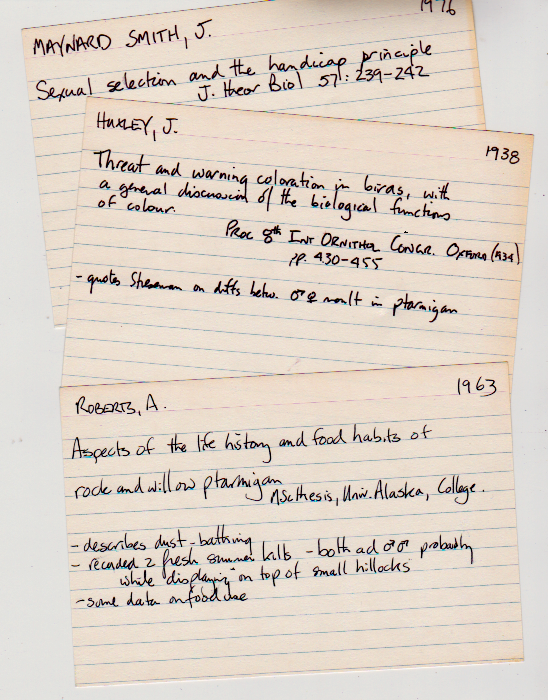

My own PhD supervisor, Peter Grant, went to the library every Friday to search and read the literature, making out file cards for every paper that interested him. And well into the 1990s, George Williams—who was an adjunct professor here at Queen’s would show up in our library every few months filling out file cards on papers that he had read. I figured that if this method was embraced by two of the great evolutionary biologists of the twentieth century it was good enough for me. By the time I finally put my file cards into the dumpster having transferred that information over to Bookends, I had accumulated >7000 cards like the ones in the picture to the right.

My own PhD supervisor, Peter Grant, went to the library every Friday to search and read the literature, making out file cards for every paper that interested him. And well into the 1990s, George Williams—who was an adjunct professor here at Queen’s would show up in our library every few months filling out file cards on papers that he had read. I figured that if this method was embraced by two of the great evolutionary biologists of the twentieth century it was good enough for me. By the time I finally put my file cards into the dumpster having transferred that information over to Bookends, I had accumulated >7000 cards like the ones in the picture to the right.

This ritual was the stock-in-trade of scientists for most of the twentieth century. While I don’t lament the demise of this weekly ritual, which consumed a huge amount of time for such a small gain in knowledge, there was something vaguely satisfying about keeping up with the literature on a regular basis. My students, of course, can’t imagine actually keeping abreast of the relevant literature in our discipline and even often baulk at reading a paper once a week for our journal club discussions.

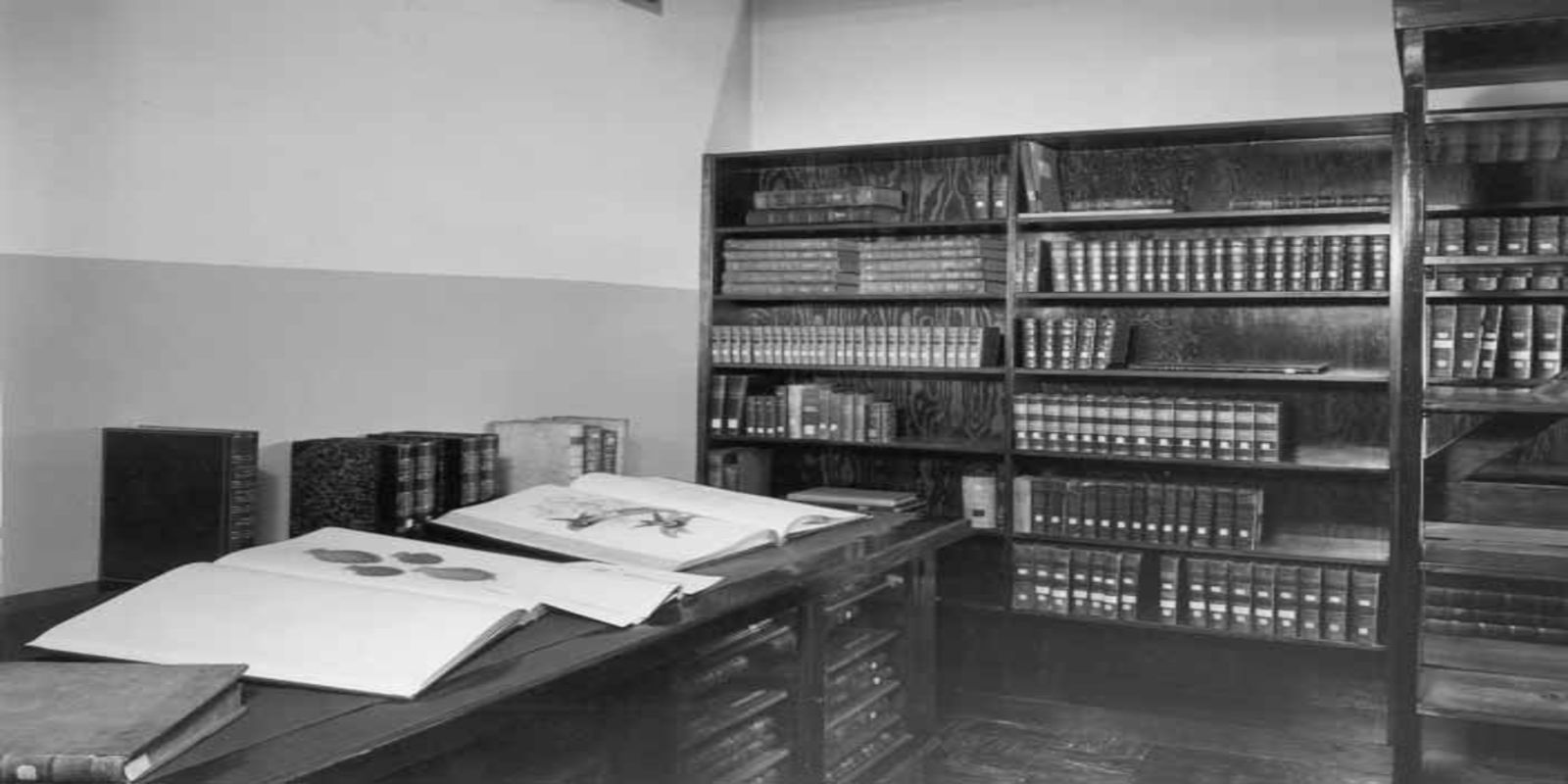

Zoological Record began publishing in 1864 as The Record of Zoological Literature and Biological Abstracts in 1926 and by the time our library stopped getting the print version, in the early part of this millennium, these two publications occupied tens of metres of shelf space. Searching those volumes was a daunting task at times, and I well remember trying to compile a complete list of papers published on hummingbird behaviour and ecology, the subject of my PhD. At least in the 1970s, that task was actually do-able, and worthwhile, as once I had finished I knew that I had the entire literature on my chosen subject at my fingertips. Getting copies of those papers was, of course, another story.

The compiling of bibliographies has a long history in the sciences, and presumably provided a very useful service for scientists who did not have ready access to extensive libraries. While today those bibliographic compilations can at first seem like a worthless anachronism, the best ones not only list what was published but also provide commentaries that are extremely useful to historians, providing contemporary insights into the perceived value of published work.

I have already mentioned here the bibliographies published by the execrable Wood brothers in the 1830s, but there are several others that form a very nice historical record of early ornithology, a few of which are listed here:

- Wood CT (1835) The Ornithological Guide: in which are discussed several interesting points in ornithology. London: Whittaker. [Available here. An odd compilation of ornithological information, including a long section (pp 79-173) in which he reviews (English) books, journals and magazines about birds from Willughby and Ray’s Ornithology (1678) to his brother Neville’s soon to be published British Songsters, which was not published until 1836 under the name British song birds: being popular descriptions and anecdotes of the choristers of the groves.]

- Wood N (1836) The Ornithologist’s Text-book: Being Reviews of Ornithological Works: with an Appendix Containing Discussions on Various Topics of Interest. London: JW Parker. [Available here. Not to be outdone by his brother Charles Thorold, Neville published his own review of books about birds in the long first section (pp 4-99) of this textbook, covering the same material as his brother but adding books written in French and German. Both of the Wood brothers are unstinting in their praise for books they liked, and highly critical of those they found to be wanting. Of James Rennies’ (1833) Alphabet of Zoology, for example, Neville says simply “A compilation of no merit”]

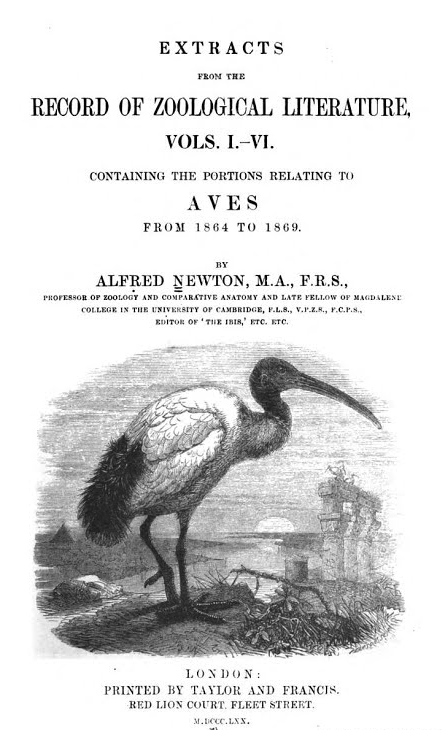

- Günther ACLG (1864) The Record of Zoological Literature. Van Voorst

Newton A (1870) Extracts from the Record of Zoological Literature, Vols. I-VI: Containing the Portions Relating to Aves, from 1864 to 1869. London: Taylor & Francis. 478 pp. [Available here. A fairly complete compilation and personal review of books and papers about birds published from 1864-1869, by the leading British ornithologist of the Victorian era]

Newton A (1870) Extracts from the Record of Zoological Literature, Vols. I-VI: Containing the Portions Relating to Aves, from 1864 to 1869. London: Taylor & Francis. 478 pp. [Available here. A fairly complete compilation and personal review of books and papers about birds published from 1864-1869, by the leading British ornithologist of the Victorian era]- Coues E (1878-80) Bibliography of ornithology. 4 Vols. US Government Printing Office. [Available here. Coues attempted to pull together the entire literature on ornithology with personal annotations, starting with 3 volumes on American ornithology and a fourth on ‘Faunal Publications relating to British Birds’ but he died before completing the entire series. Here’s what he thought of all that work

I think I never did anything else in my life which brought me such hearty praise—immediate and almost universal recognition, at home and abroad, from ornithologists who knew that bibliography was a necessary nuisance and a horrible drudgery that no mere drudge could perform. It takes a sort of an inspired idiot to be a good bibliographer, and his inspiration is as dangerous a gift as the appetite of the gambler or dipsomaniac—it grows with what it feeds upon, and finally possesses its victim like any other invincible vice. Perhaps it is lucky for me that I was forcibly divorced from my bibliographical mania; at any rate, years have cured me of the habit, and I shall never again be spellbound in that way. Coues 1897 The Osprey 2:39-40

- Mullens WH (1908) A list of books relating to British Birds published before the year 1815. Hasting and St Leonard’s Natural History Society, Occasional Publications No. 3:1-34. [A pamphlet that became the basis for his further publications listed below]

- Mullens WH, Swann HK (1919) A bibliography of British ornithology from the earliest times to the end of 1912. London: Macmillan. [Available here. The most comprehensive listing of books and papers on British birds, essentially completing the task that Coues had begun 40 years earlier]

- Zimmer JT (1926) Catalogue of the Edward E. Ayer Ornithological Library. Field Museum of Natural History, Publication 239, 240 Vol. xvi:1–706. [Available here. Like Casey Wood’s work, below, this is a comprehensive annotated listing of the publications held in a superb ornithological library at the Field Museum in Chicago]

- Wood CA (1931) An introduction to the literature of Vertebrate Zoology. London: Oxford University Press. [Available here. Casey Wood was not related to the Wood brothers (as far as I can tell) but did a magnificent job of listing and summarizing all of the books on birds in the extensive ornithological library that he established at McGill University in Montreal. Wood includes in this volume, chapters full of historical information on early ornithology gleaned, I assume, from the books in this marvellous library.]

Pittie A (2010). Birds in Books: Three Hundred Years of South Asian Ornithology—-A Bibliography. Permanent Black: India. [A comprehensive, annotated listing of about 1,700 books that contain information about the birds of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Tibet. Includes a brief overview of the history of ornithology in the region since 1700 and short biographies of about 200 prominent ornithologists whose books are included in the annotated list.]

Pittie A (2010). Birds in Books: Three Hundred Years of South Asian Ornithology—-A Bibliography. Permanent Black: India. [A comprehensive, annotated listing of about 1,700 books that contain information about the birds of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Tibet. Includes a brief overview of the history of ornithology in the region since 1700 and short biographies of about 200 prominent ornithologists whose books are included in the annotated list.]

This list is certainly far from comprehensive and I will add to it on a page on the History of Ornithology website here as I discover more volumes like these. I would have thought that Zoological Record, Biological Abstracts, as well as Web of Science, Google Scholar and the like would have marked the end of such bibliographies in the early part of the 20th century, if only because the task would now be so daunting as to be virtually impossible. The recent work by Pittie suggests that maybe there is still a market for and interest in these compilations, but I doubt it.

For a century, though, possibly beginning with the books by Charles and Neville Wood, books about books about birds were an invaluable guide for ornithologists, and helped to avoid redundancy in the naming of species. Today, they provide an invaluable historical record about the beginnings of scientific ornithology.

It’s worth noting that the Biodiversity Heritage Library https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ (a consortium of many Natural History Libraries) has full text searching and indexing of scientific names.