Twenty years ago when I was writing The Red Canary—the story of how in the 1920s a bird enthusiast and a biology teacher created a red canary—I needed to include an overview of the history of canary domestication. To obtain the necessary information, I started to collect eighteenth- and nineteenth-century books on canary breeding. As this was before many of these books became available on-line, I regularly checked for editions available at local and international booksellers.

Twenty years ago when I was writing The Red Canary—the story of how in the 1920s a bird enthusiast and a biology teacher created a red canary—I needed to include an overview of the history of canary domestication. To obtain the necessary information, I started to collect eighteenth- and nineteenth-century books on canary breeding. As this was before many of these books became available on-line, I regularly checked for editions available at local and international booksellers.

Charles Darwin’s book The Variation in Animals and Plants under Domestication, from 1868, provided an overview of variation, selective breeding and the process of domestication. In it, he covered the domestication of dogs, cats, pigeons, chickens, and (briefly) the canary. As his main source of information on the canary, Darwin cited a book by Bernard Brent [1]. Brent was a shipbuilder who was also a pigeon, poultry and cage bird enthusiast. He lived not far from Darwin and was a regular contributor to the Cottage Gardener [2] to which Darwin subscribed.

I eventually obtained a wide range of books on canaries, but Brent’s book, The Canary, British Finches, and some other Birds, eluded me. Despite regular inspection of the on-line second bookshops over several years, I never once saw Brent’s book offered for sale. Although this was slightly frustrating, it was not a major obstacle for my research since, I was able to use the copy once owned by Darwin himself, in the Cambridge University Library.

The apparent scarcity of Brent’s book made me suspect that only a few copies had been printed, but it also made me wonder whether Brent might not have been highly rated by the cage-bird cognoscenti. This view was reinforced, when I discovered that Brent had made a mistake—and one that Darwin repeated in Variation [3]—when he claimed that there existed a feather-footed breed of canaries. Brent had obtained this information from a mistranslation of the word ‘duvet’ (meaning down feathers) as ‘rough-footed’ (for unknown reasons) in the English edition of a well-known book about canaries by the French author J-C. Hervieux [4]. In his book, Brent wrote: “The rough-footed or feather-legged Canaries now seem to be very scarce, if the breed is not altogether lost, as I do not remember having seen but one, and that many years back.” [5] This suggests that he thought he may have seen one, which, of course, he could not have done as they do not exist.

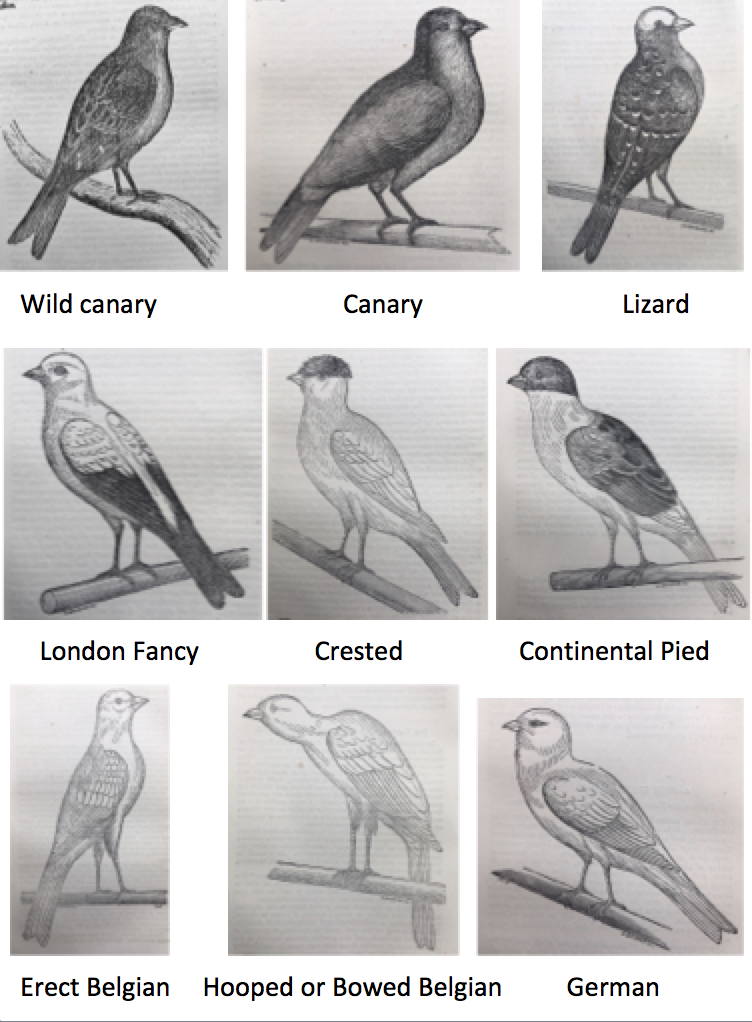

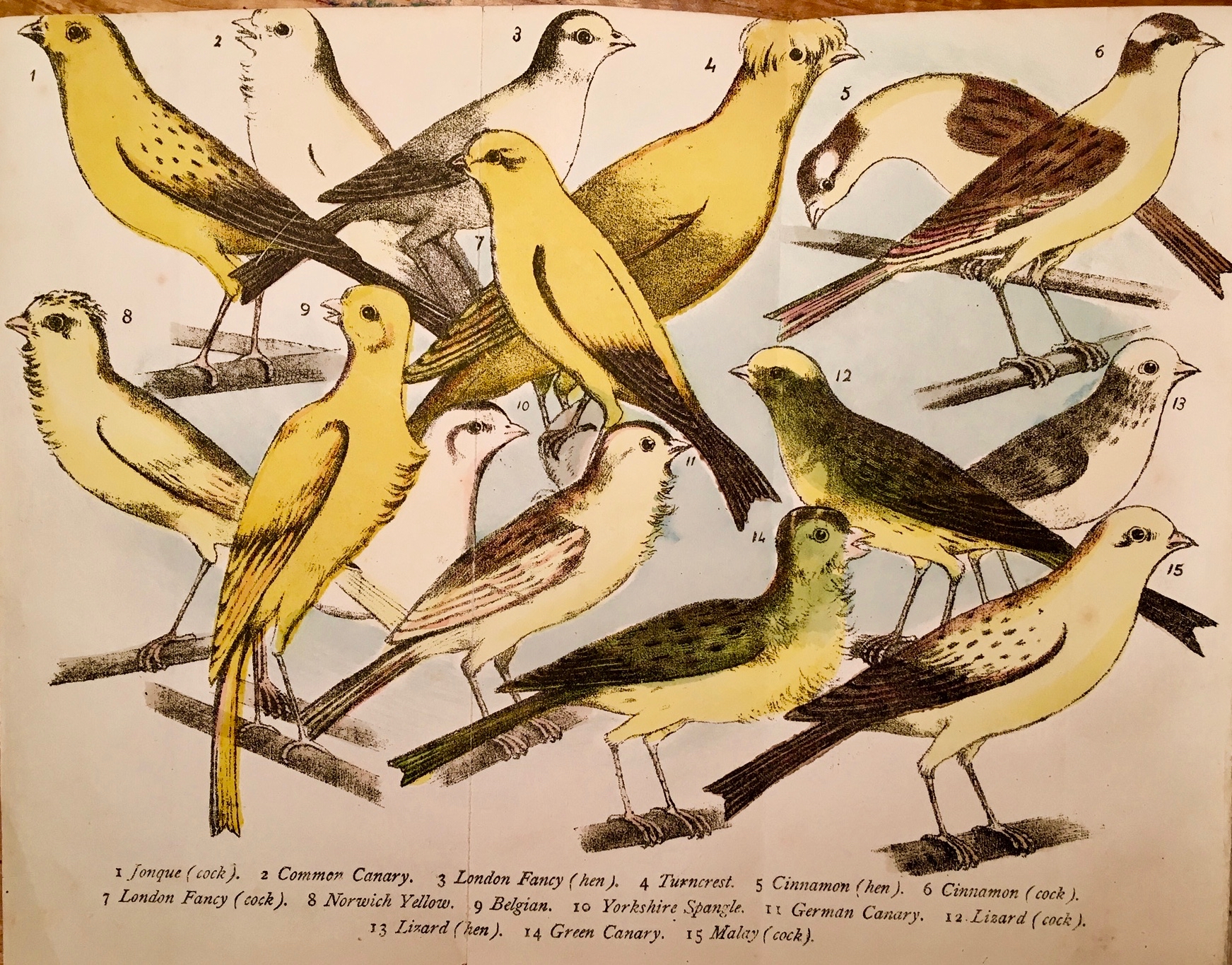

My scouring of the on-line second-hand bookshops identified some twenty other books on canaries that Darwin could have cited in Variation, so why did he use Brent? The main reason I think was that Brent was one of first to enumerate and illustrate the different canary breeds. The drawings aren’t great (see illustration to the left [6]), but as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. A further five or ten years were to pass before images of the different breeds in colour became available (see below).

Darwin knew Brent personally. They first met after Darwin became interested in the artificial selection of pigeons in 1855 and attended a fanciers’ meeting in London [7]. After this initial encounter Darwin wrote to his son William referring to Brent as “a very queer [meaning unusual] little fish”, adding that “all pigeon fanciers are little men, I begin to think” [8]. Brent was indeed small in stature [9] and, according to Darwin. both “a very obliging kind man, but very crotchetty” [10] and “eccentric” [11]. Nevertheless, Brent and Darwin corresponded and Brent visited Darwin’s home [12] and became Darwin’s chief source of poultry information [13], as well providing other details such as the breeding canary-finch hybrids [14]. It is also possible that Brent gave Darwin the copy of his Canary book.

Last week, some fifteen years after The Red Canary was published, I was looking for another old bird book on-line. Failing to find it reminded me of my earlier quest for Brent’s book. I looked again, and to my amazement, there was copy in a bookshop on England’s south coast. I couldn’t resist it—hence the inspiration for this essay.

SOURCES

- Anonymous (1873) Canaries: their Varieties and Points. London: Dean.

- Birkhead TR (2003) The Red Canary. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson [published in the USA as A Brand New Bird. New York: Basic Books; and reprinted by Bloomsbury, London in 2014].

- Brent BP (1855) The Cottage Gardener 15: 16 Oct pages 42-43, 13 Nov pages 115-116, and 11 December pages 184-185

- Brent BP (1864) The canary, British finches, and some other birds: including directions for their management and breeding in the cage and aviary ; as well as the treatment of their diseases; with numerous illustrations. London: Journal of Horticulture & Cottage Gardener Office.

- Darwin C (1868) The Variation in Animals and Plants under Domestication. London: John Murray.

- Hervieux de Chanteloup J-C (1718) A New Treatise of Canary Birds. London: Bernard Lintot, London. [Available here. This is an English translation of Hervieux de Chanteloup J-CC (1709) Nouveau traité des Serins de Canarie. Paris: Claude Prodhomme. Available here]

- Irwin R (1951) British Bird Books: an index to British ornithology, A.D. 1481 to A.D. 1948. London: Grafton & Co.

-

Mullens WH, Swann HK (1919) A Bibliography of British Ornithology from the Earliest Times to the End of 1912, including biographical accounts of the principal writers and bibliographies of their published works. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited.

-

Wood CA (1931) An Introduction to the Literature of Vertebrate Zoology. London: Oxford University Press.

Footnotes

- a book by Bernard Brent: still not available anywhere online. Brent’s book is not listed in any of the bibliographies in my library, including: Wood (19310, Irwin (1951), and Mullens & Swan (1917). This is, in itself, is a quite telling indication of the scarcity of Brent’s. book. In 1878, Brent’s book sold for 1s. 6d. [the equivalent of US$11.15 in today’s currency]. Bernard Peirce Brent (1822-1867) lived at Bessels Green, Riverhead, in 1857, only 15 km from Darwin’s house in Downe, Kent

- The Cottage Gardener: from 1849-1855 published under this name for volumes 1-15 [vol 1-11 available here, but vol 15 with Brent’s article curiously unavailable online] then from 1861-1871 as Journal of horticulture, cottage gardener and country gentlemen with the new series starting with volume 1 in 1861 [vols 1-4, 6-8, 19-21, and 23 available here]

- Darwin repeated in Variation: as a result this mistake was repeated by others, trusting Darwin

- J-C. Hervieux: Jean-Claude Hervieux de Chanteloup (1683-1747) was inspecteur des bois à batir [timber inspector] in Paris, and looked after canaries owned by the Princesse de Condé who lived in the palace at Chantilly and to whom Hervieux dedicated his book

- two quotations: from Brent 1864, page 22

- Brent’s illustrations: the drawings are from Brent (1864) but I have added the names that he used

- attended a pigeon fanciers’ meeting in London: Darwin attended a meeting of the Columbarian Society, near London Bridge, on the 29 November 1855.

- quotation: see Darwin Correspondence Project Corr 5: 509

- small in stature: see Darwin Correspondence Project, Corr. 15: 119

- “…very crochetty”: see Darwin Correspondence Project, Corr. 13, Suppl. : 443 [see here]

- “eccentric”: see Darwin Correspondence Project, Corr. 15: 337 [see here]

- Brent visited Darwin’s home: see Darwin Correspondence Project, Corr. 5: 247

- Darwin’s chief source of poultry information: see Darwin Correspondence Project, Corr. 5: 60 n6

- breeding canary-finch hybrids: see Darwin Correspondence Project, Corr. 5: 470

IMAGES: Red Canary cover by the author; Brent portrait from a site summarizing his family tree and relation to Isaac Newton [here]; canaries from Brent (1864) and Anon (1873) are from the author’s copies