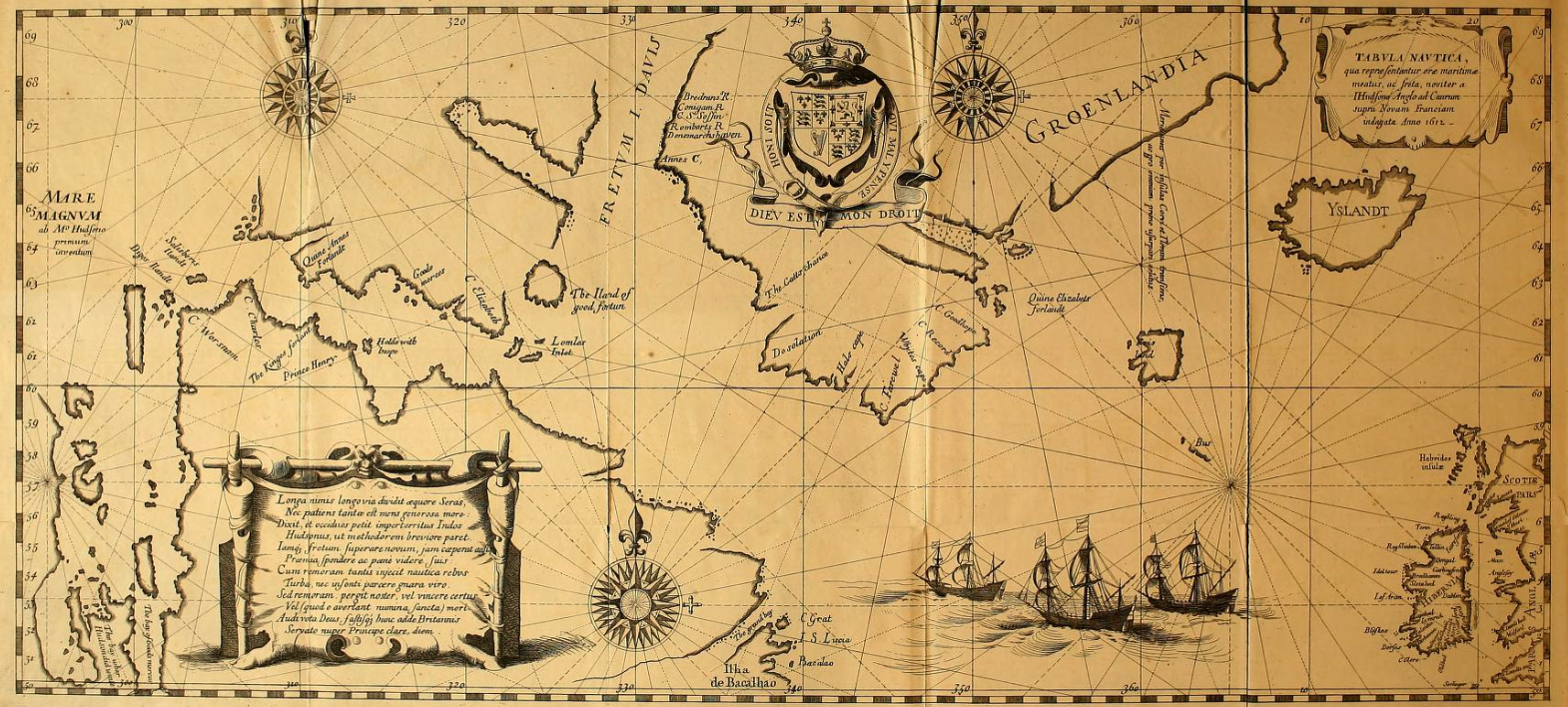

Four hundred and eight years ago this month—in August 1610—Henry Hudson and his crew of 21 on the tiny ship DISCOVERY entered Hudson’s namesake bay in search of a northwest passage to the orient. As far as we know, Hudson’s 1610-1611 expedition was the first time that Europeans had recorded the sighting of an identifiable arctic bird on its breeding grounds in North America. Martin Frobisher, for example, had previously visited Baffin Island three times in a vain attempt to mine for gold [1] but he made virtually no note of the birds [2].

Hudson’s crew famously mutineed in June 1611 after a dreadful winter spent on their ship trapped in the ice of James Bay. The 12 mutineers set Hudson, his son, and 7 loyal seamen adrift in rowboat and their fate is still unknown [3]. What we do know about Hudson’s final expedition comes from the writings of one of the mutineers, Abacuk Prickett, who wrote about it after returning to England [4]. Prickett was one of the four mutineers who was tried (and acquitted) for the mutiny, and there has always been some suspicion that his narrative was biased in a way that was designed to save him from the gallows. Nonetheless, there is no reason to expect that his account of the birds is not as accurate as could be expected for a document being written, we presume, largely from memory.

Prickett records that their first landfall in the Canadian arctic was in July 1610 on the ‘Iles of Gods Mercie’, probably the islands off the south coast of Baffin Island [5] near the present-day settlement of Kimmirut (formerly Lake Harbour) in Nunavut. There, they “sprung a covey of partridges which were young: at the which Thomas Woodhouse shot, but killed only the old one” [6]. Given the current breeding ranges of the two arctic ptarmigans, these were almost certainly Rock Ptarmigan, which makes it the first bird species recorded in Arctic North America and, fittingly, the official bird of Nunavut.

Their next landfall was at Digges Island [7] on 3 August. A small crew went ashore, including Prickett who said “In this place a great store of fowle breed…” [8], almost certainly referring to the huge colony of Thick-billed Murres nesting on the cliffs there, today numbering some 300,000 breeding pairs.

On Digges, Prickett also noted that “Passing along wee saw some round hills of stone, like to grasse cockes, which at the first I tooke to be the worke of some Christian. Wee passed by them, till we came to the south side of the hill we went unto them and there found more; and being nigh them I turned off the uppermost stone, and found them hollow within and full of fowles hanged by their neckes.” [8]. What he is referring to here are small domed stone huts, about 2 m in diameter, built by the local Inuit to hang, dry and protect their game from predators.

Remarkably, my colleague Tony Gaston, who studied the murres on Digges in the 1980s, found at least four of the same drying huts described by Prickett. As Gaston noted, these are very similar to a structure called a ‘clett’ (also ‘clet’) that the inhabitants of the Outer Hebrides use to dry and cure fish and birds (see photo).

From Digges, the explorers headed south, ecstatic that they might have found the passage to China, as winter approached. By the time they reached James Bay, they knew that there nowhere near the orient. But on 10 November DISCOVERY was trapped in the sea ice so the crew prepared for the winter. During that harsh winter, they often went ashore to hunt, taking as many as 1200 ptarmigan, enough for each man to have one to eat every day or two for three months: “for the space of three moneths wee had such store of fowle of one kinde (which were partridges as white as milke) that wee killed above an hundred dozen, besides others of sundry sorts…The spring coming this fowle left us, yet they were with us all the extreame cold. Then in their places came divers sort of other fowle, as swanne, geese, duck, and teale, but hard to come by.” [9]

With the ship freed from the ice, the mutineers set Hudson and the others adrift at the top of James Bay in June 1611, and headed back to Digges to stock up on murres and their eggs for the trip home. There, they encountered a band of the local Inuit collecting eggs and catching adult murres with a noose, much the same way that today’s researchers catch murres for banding: “Our boat went to the place where the fowle bred, and were desirous to know how the savages killed their fowle: he shewed them the manner how, which was thus: they take a long pole with a snare at the end, which they put about the fowles necke, and so plucke them downe. When our men knew that they had a better way of their owne, they shewed him the use of our peeces, which at one shot would kill seven or eight.” [10]

The natives became frightened and suspicious of the mutineers, attacking an unarmed party that had gone ashore one day to shoot some murres. Three of that party were killed but the others escaped. The remaining mutineers went to another part of the colony where they shot enough birds to (barely) get them home.

None of these vague observations of birds by Prickett really made any useful contribution to ornithology, and I tell this story mainly as an introduction to the history of ornithology in the North American Arctic. By the late 18th century, explorers and naturalists were making regular forays into what is now Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, Yukon, and Alaska. Those later expeditions did make many useful contributions to ornithology, finding the breeding grounds and documenting the breeding biology of many Arctic birds for the first time.

Some of this early Arctic ornithology is described in a forthcoming 2-volume book on the Birds of Nunavut that will be launched at the upcoming IOC meeting in Vancouver. I wrote the history chapter for that book, but the limitations of space meant that many stories, images, and details had to be left out. As for much of the history of ornithology, this blog provides a unique opportunity to expand on the details of scholarly books and papers, as I have done here with the story of Abacuk Prickett.

Some of this early Arctic ornithology is described in a forthcoming 2-volume book on the Birds of Nunavut that will be launched at the upcoming IOC meeting in Vancouver. I wrote the history chapter for that book, but the limitations of space meant that many stories, images, and details had to be left out. As for much of the history of ornithology, this blog provides a unique opportunity to expand on the details of scholarly books and papers, as I have done here with the story of Abacuk Prickett.

SOURCES

-

- Collinson R, editor (1867). The Three Voyages of Martin Frobisher, in Search of a Passage to Cathaia and India by the North-West, A.D. 1576-8. London: Hakluyt Society. [available here]

- Gaston AJ, Cairns DK, Elliot RD, Noble DG (1985) A natural history of Digges Sound. Canadian Wildlife Service Report Series 46:1–63.

- Mancall PR (2009) Fatal Journey: The Final Expedition of Henry Hudson. New York: Basic Books.

- Prickett A (1860). A larger discourse of the same voyage, and the successe thereof. In G. M. Asher (Ed.), Henry Hudson the Navigator: the original documents in which his career is recorded (pp. 98-36). London: Hakluyt Society. [available here]

- Richards JM, Gaston AJ, editors (2018) Birds of Nunavut. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Footnotes

- Frobisher mining for gold: on his third expedition in 1578, for example, he took back to England 1350 tonnes of ore from the vicinity of Iqaluit (formerly Frobisher Bay) only to discover when he got back to England that the ‘gold’ was iron pyrite. No doubt he felt like a fool.

- Frobisher’s birds: Collinson (1867) has only three mentions of birds (fowle) in Frobisher’s writings and these were all with reference to birds and eggs being caught by the natives for food. It is impossible to know what birds he was talking about.

- Hudson’s fate unknown: there is speculation, however, that the men made their way south where were taken captive by the natives, then transported to the vicinity of Ottawa, Ontario (see here for details)

- Prickett’s account of the expedition: see Prickett (1860), in a volume by the Hakluyt Society, established in 1846 to publish original accounts of voyages of discovery. Prickett’s account was actually first published in 1825. Prickett is often spelled ‘Pricket’ but I am using the spelling on his account in the 1860 volume.

- Iles of God’s Mercie: these are shown on Hudson’s map (above), offshore where he labels ‘Goods Merces’

- Quotation about partridges: from Prickett 1860 page 103

- Digges Island: Hudson named this Deepes Cape, thinking initially that it was part of the mainland

- Quotations about ‘fowles’: from Prickett 1860, page 107

- Quotation about hunting birds in winter and spring: from Prickett 1860, page 113

- Quotation about Inuit method of catching murres: from Prickett 1860, page 128

IMAGES: Hudson map from the frontispiece of Asher (1860) where Prickett’s account was published; Clets on St Kilda from Wikimedia Commons; Digges Island photo by Leslie M. Tuck in the author’s collection; book cover from UBC Press.

COMMENTS