When I was first starting to learn about birds, I was particularly intrigued (and delighted) with the peculiar names that had come from old English (dunlin, cormorant) and other languages (guillemot, eider), and those that were onomatopoeic (cuckoo, chickadeee). I also assumed that those birds named after people (Audubon’s Warbler, Temminck’s Stint, Townsend’s Warbler) were a nice touch, maybe honouring those early naturalists who had either discovered those birds or studied them in some detail. It seems that bird names must be generally interesting to birders and ornithologists as there are more than a dozen books and papers on the origins of English (common) bird names dating back into the 1800s [1].

Recently, while putting together some material on the history of Arctic ornithology, I discovered, somewhat to my dismay, that the naming of birds after people was not nearly as rational or commemorative as I had once thought. I had assumed, for example, that the lovely Ross’s Goose had been named after Admiral Sir John Ross, the Scotsman who explored the Canadian Arctic in the early 1800s in search of a Northwest Passage with William Parry. Or maybe even after Captain Sir James Clark Ross, John’s nephew, who also explored the Canadian Arctic, but is more famous for his Antarctic exploits. Indeed, James Ross was maybe the more likely candidate as he was something of a naturalist where John Ross was not. Many famous early explorers were also naturalists who contributed immensely to our early knowledge of Arctic birds, so it seemed to me that it was reasonable to have immortalized them in the common (and scientific) names of birds.

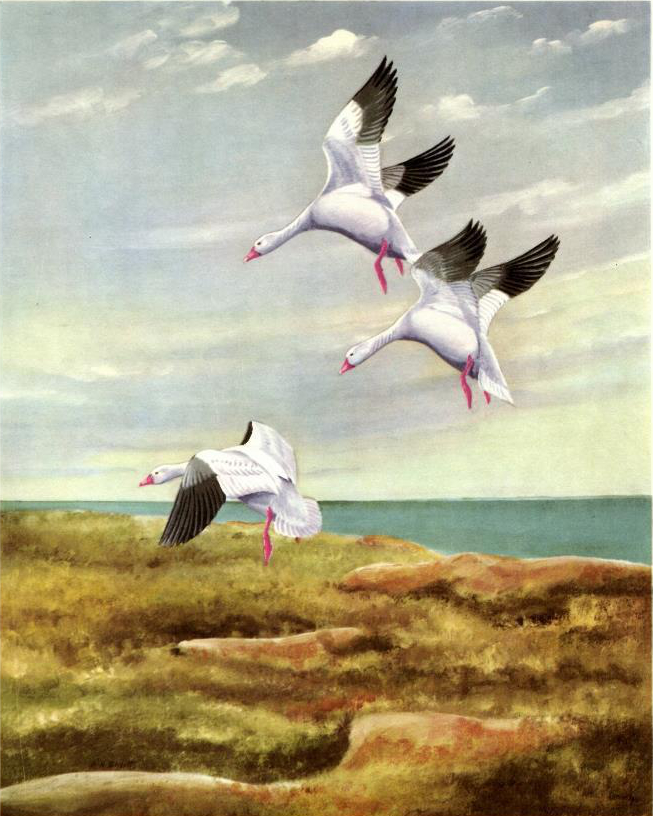

The Ross’s Goose was actually named, in 1861, after Bernard Rogan Ross, a Hudson’s Bay Company clerk and chief trader at various settlements (forts) owned by the company in what was called, in those pre-Canada days, The North-Western Territory and Rupert’s Land [2]. Ross was a keen naturalist who sent hundreds of specimens to the Smithsonian in Washington and the British Museum (Natural History) in London, along with excellent notes on the habitats and nesting habits of each species that he collected. He also published on mammals, birds, and ethnographic topics in 1861 and 1862 [3].

The Ross’s Goose was actually ‘discovered’ almost a century earlier, in the 1760s, and given the English name ‘Horned Wavey’ in 1795, by the great Arctic explorer and naturalist Samuel Hearne, who wrote:

HORNED WAVEY. This delicate and diminutive species of the Goose is not much larger than the Mallard Duck. Its plumage is delicately white, except the quill-feathers, which are black. The bill is not more than an inch long, and at the base is studded round with little knobs about the size of peas, but more remarkably so in the males…about two or three hundred miles to the North West of Churchill, I have seen them in as large flocks as the Common Wavey, or Snow Goose. The flesh of this bird is exceedingly delicate; but they are so small, that when I was on my journey to the North I eat two of them one night for supper. I do not find this bird described by my worthy friend Mr. Pennant in his Arctic Zoology. Probably a specimen of it was not sent home [4]

Despite the fact that Hearne had shot (and eaten!) this bird, there were no specimens, and no attempt to give it a scientific name for quite some time. In 1859, Robert Kennicott sent a head, wings, tail and head of a Ross’s Goose plus a nearly complete skin (that he had obtained from Bernard Ross) to the Smithsonian [5]. The species was then formally described in 1861 as Chen rossii by John Cassin, ornithologist at the Philadelphia Academy of Sciences. I don’t really have a problem with Bernard Ross being recognized in this bird’s scientific name, for he did collect the first specimen to be preserved in a museum. But it would be fitting for the common name to be Hearne’s Goose, as Hearne actually was the first to recognize it as distinctive, and he made huge contributions to Arctic ornithology.

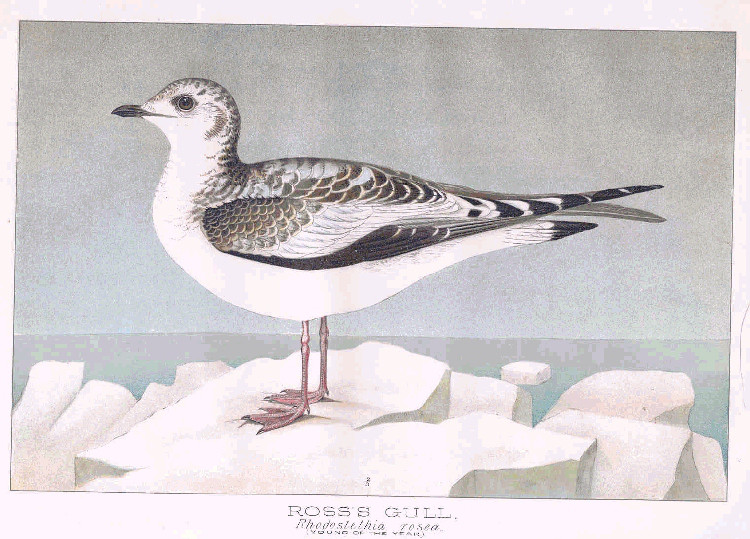

The Ross’s Gull, on the other hand, is named after James Clark Ross, but even that troubles me a bit. Ross (or a member of his party) collected the first specimens of this beautiful gull in Foxe Basin off the east coast of Nunavut’s Melville Peninsula in June 1823. Ross really did little more than send the specimens of two odd-looking gulls back to England. William Macgillivray mentioned these specimens in a 1824 in a footnote to a paper on gulls, where he says that the name Larus roseus is: “The name given pro tempore to a new species of gull, discovered by the Arctic expedition, but which is to receive its proper designation from Dr Richardson.” [6] The ‘Dr Richardson’ that he refers to here is the great Arctic naturalist John Richardson who identified the bird as a distinct species and described it—as the Cuneate-tailed Gull Larus Rossii—in 1824 in his appendix to Parry’s journal of his second voyage. Richardson, rather than Ross, should really have been immortalized in this species’ common name. Richardson loses doubly on this one because the rules of zoological nomenclature require that Macgillivray be listed after the scientific name because he was the first to publish—by only a few months— that name even though he was just vaguely referring to Richardson. Moreover, Macgillivray referred to the bird as Larus roseus and not Larus Rossii that Richardson seem to prefer.

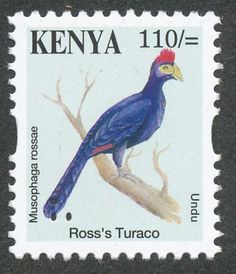

There is one other bird named Ross—the Lady Ross’s Turaco—which has, like the other Ross’s birds, what seems to me to be an inappropriate common name. Lady Eliza Solomon Ross was the wife of Major General Sir Patrick Ross [7], the governor of St Helena from 1846-1850. St Helena is a tiny tropical island in the mid-Atlantic about 2000 km west of Namibia. It became a British Crown Colony in 1836 after being ‘owned’ by the East India Company for more than 150 years. The St Helena Rosses were not, as far as I can tell. closely related to the James, John or Bernard Ross mentioned above.

There is one other bird named Ross—the Lady Ross’s Turaco—which has, like the other Ross’s birds, what seems to me to be an inappropriate common name. Lady Eliza Solomon Ross was the wife of Major General Sir Patrick Ross [7], the governor of St Helena from 1846-1850. St Helena is a tiny tropical island in the mid-Atlantic about 2000 km west of Namibia. It became a British Crown Colony in 1836 after being ‘owned’ by the East India Company for more than 150 years. The St Helena Rosses were not, as far as I can tell. closely related to the James, John or Bernard Ross mentioned above.

Lady Ross must have kept a small menagerie or aviary on St Helena that included a turaco brought there from the west coast of Africa [8]. On a visit to England she gave two feathers and a drawing (by a Lieutenant J. R. Stack) of her bird to John Gould, presumably wondering what species it was. Based on that material, Gould described this individual as a new species at a meeting of the Zoological Society of London in 1851 [9].

In my opinion, either John Gould—or nobody—should have been immortalized in the common name of that turaco, and certainly not Lady Ross.

The naming of birds has a long and checkered—and interesting—history that continues even today. I see, for example, that the AOS checklist committee is currently wrestling with some proposed changes to the common names of North American birds, to right some perceived wrongs (Gray Jay to Canada Jay, and Rock Pigeon to Rock Dove), harmonize names between Europe and the Americas (Common Moorhen to Eurasian Moorhen, and Common Gallinule to American Moorhen), and to indicate the correct taxonomic affinities (Red-breasted Blackbird to Red-breasted Meadowlark).

It is perhaps rather ironic that four of the ornithologists directly involved in what I consider to be the misnaming of the three Ross’s birds have all been immortalized—and rightly so—in the common names of other birds—Cassin’s Auklet, Townsend’s Warbler, Gouldian Finch, Macgillivray’s Warbler, for example. While I consider the Ross’s birds to be misnamed—or at least inappropriately named—I would not suggest changing those names as they are well established. The origins of those common names also provides an interesting window on the state of ornithology in the 1800s. As Macgillivray said in the paper where he first listed the scientific name of the Ross’s Gull: “With regard to the outcry against change of names, I have only to observe, that names, as well as descriptions, must continue to fluctuate until they be rendered of such a nature as to be harmonized with common sense and sound judgment.” [10]

SOURCES

-

Baird SF, Brewer TM, Ridgway R (1884) The Water Birds of North America. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

-

Cassin J ( 1861). Permission being given, Mr. Cassin made the following communication in reference to a new species of Goose from Arctic America. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 13: 72-72

- Grant CHB (1915) On a collection of birds from British East Africa aid Uganda, presented to the British Museum by Capt. G. P. Cosens.-Part 111. Colii-Pici. Ibis 57: 400-473

- Hearne S (1795) A Journey From Prince of Wales’s Fort in Hudson’s Bay to the Northern Ocean. London: Strahan and Cadell.

- Macgillivray W (1824) Descriptions, characters, and synonyms of the different species of the genus Larus, with critical and explanatory remarks. Memoirs of the Wernerian Natural History Society 5: 247-276

- Nelson EW (1887) Report upon Natural History Collections Made in Alaska Between the Years 1877 and 1884. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office

-

Parry WE (1824) Journal of a second voyage for the discovery of a northwest passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific; performed in the years 1821-22-23, in His Majesty’s ships Fury and Hecla, under the orders of Captain William Edward Parry. London: John Murray.

-

Pennant T (1784) Arctic Zoology, 2 vols. London: Henry Hughs.

-

Ross BR (1862) List of mammals, birds, and eggs observed on the Mackenzie River District, with notices. Canadian Naturalist 7:137-155

-

Swainson C (1885) Provincial names and folk lore of British birds. London: English Dialect Society.

-

Whitman CH (1898) The birds of Old English literature. The Journal of [English and] Germanic Philology 2:149–198.

Footnotes

- old books about bird names: see, for example, Swainson (1885) and Whitman (1898)

- North-Western Territory and Rupert’s Land: Ross was employed from 1843-1862 at the Hudson’s Bay Company trading posts at Norway House and York Factory in present-day Manitoba, as well as Fort Simpson, Fort Norman, and Fort Resolution in the present-day Northwest Territories

- Bernard Ross publications: e.g. Ross (1862); see here for a listing

- quotation: from Hearne 1795, page 412; Hearne wrote that passage long after he returned to England and was presumably surprised to learn that there were no specimens in Pennant’s book, published in 1784; Hearne died in 1793 and his Journey was published posthumously

- Ross’s Goose specimens: Kennicott also collected “a large number of individuals of this species” (Baird et al. 1884, page 446)) at Fort Resolution in 1860, and I am surprised that Cassin did not honour him in the scientific name of this species

- quotation from footnote on Ross’s Gull: Macgillivray 1824, page 249

- Lady Eliza Solomon Ross : some sources incorrectly identify this Lady Ross as Sir James Ross’s wife.

- west coast of Africa: possibly Angola, see Grant 1915 page 413

- turaco described by Gould: presumably Lady Ross later gave the turaco to Gould because it is now a specimen in the BM(NH) “the type, which is a worn and faded caged bird” (Grant 1915, page 413)

- quotation on changing bird names: Macgillivray 1824, page 276

Bob,

Most enjoyable. The history and use of birds names is fascinating. There are a couple of dictionaries of US bird names (Holloway, 2003: Loose, 1989; Gruson, Choate, 1983; Stickney, 2009) that are fun to ponder. I think Elliot Coues bio (Cutright & Brodhead, 1981) is a good introduction to the battles within the AOU on the use of trinomials, thinking about species, etc., is also interesting.

This is not a topic I have explored much…yet, so thanks for those references. I have, however, read a lot about that debate about trinomials in the late 1800s and will report on that in the blog some day soon. There are certainly many book about bird names that I will add a page of references to the History website as soon as I get a chance as others might find that compilation useful.