Birds’ eggs can bring out the worst in people. In the UK, for example, the avaricious collecting of birds’ eggs more than 60 years ago threatened or hastened local extinctions of rare raptors and the endangered red-backed shrike Lanius collurio, whose beautifully marked eggs seemed irresistible to collectors.

Egg collecting, or öology as it was once known, became illegal in the UK in 1954, and collectors have since been excoriated to such an extent than even the sight of a clutch of eggs in a museum can trigger an indignant outburst. A colleague was given a copy of my book The Most Perfect Thing: the Inside (and Outside) of a Bird’s Egg by his partner, but she said that she wouldn’t be reading it because the thought of eggs and egg collecting made her feel sick. Many museums that have acquired öologists’ collections are reluctant to display those eggs for fear of deterring visitors.

Nowhere was this attitude more prevalent than in a recent exhibition. The idea was to display birds’ eggs as ‘art’, but overlain with a sense of self-righteous condemnation of those who had collected them. The irony was that the eggs on display were replicas—and rather clumsily done at that—because the originals, confiscated from a collector, were reported to have been ‘officially’ destroyed. Exhibiting crude replicas of eggs was as much art as replacing paintings in the National Gallery with coloured photocopies would be. Having rarely had the opportunity to see the eggs of wild birds, the vast majority of exhibition visitors knew no different.

In the late 1800s, when Oscar Wilde wrote the words in the title of this essay, the eggs of wild birds were still a great adventure for both scientists and hobbyists. Eggs were first collected in earnest at the beginning of the scientific revolution when they became objects of curiosity to be added to the cabinets of wealthy virtuosi. The physician, Sir Thomas Browne, who was also a naturalist and polymath, was among the first to make such an egg collection in the 1650s.

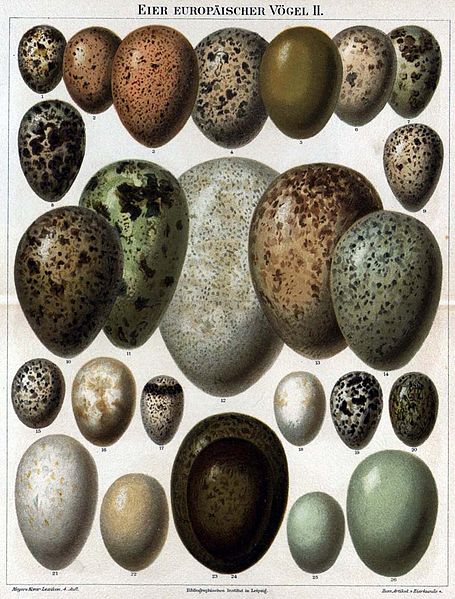

As science gained stature, egg collecting became increasingly widespread, morphing into ‘öology’ in the optimistic belief that egg shape, colour, and size might inform the on-going quest to discover the true natural order (phylogeny) of birds. By the 1890s, as the great Victorian ornithologist Alfred Newton made clear, this was a lost cause, as indeed it was with many of the morphological traits of the birds that taxonomists used to try to construct a phylogeny.

As science gained stature, egg collecting became increasingly widespread, morphing into ‘öology’ in the optimistic belief that egg shape, colour, and size might inform the on-going quest to discover the true natural order (phylogeny) of birds. By the 1890s, as the great Victorian ornithologist Alfred Newton made clear, this was a lost cause, as indeed it was with many of the morphological traits of the birds that taxonomists used to try to construct a phylogeny.

Despite this lack of scientific success, öology continued apace through the early 1900s, with most schoolboys (rarely girls) collecting eggs. A few continued to collect to eggs as adults, by which time—for most of them— it had become an obsession. By the 1920s, there were rumblings of discontent in some quarters as the need for bird protection was becoming more apparent.

After egg collecting became illegal in 1954 in the UK, egg collections moved from private ownership into museums. Today, as the last of the pre-1954 collectors reach the ends of their lives, private egg collections continue to be added to those in museums in the form of bequests, although there are those that would rather see such collections shattered rather than saved for posterity.

The truth is that museum egg collections have served a valuable scientific role, helping, for example, to identify and resolve environmental problems associated with the insidious effects of DDT and acid rain. Collections of eggs have also informed us about evolution, and in particular the co-evolutionary arms races between brood parasites and their hosts—exemplified by the work of Claire Spottiswoode.

Recently, the vast egg collection of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at Berkeley has provided data for a comparative study of egg shape by Cassie Stoddard and colleagues that promises to fuel new interest in this topic.. Environmental problems such as climate change will continue to challenge biologists trying to stem the worldwide decline in bird numbers. The collections of eggs in museums may well serve once again to help resolve environmental problems that we haven’t yet even begun to imagine.

Recently, the vast egg collection of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at Berkeley has provided data for a comparative study of egg shape by Cassie Stoddard and colleagues that promises to fuel new interest in this topic.. Environmental problems such as climate change will continue to challenge biologists trying to stem the worldwide decline in bird numbers. The collections of eggs in museums may well serve once again to help resolve environmental problems that we haven’t yet even begun to imagine.

SOURCES

- Birkhead, T. R. The Most Perfect Thing: the Inside (and Outside) of a Bird’s Egg. Bloomsbury, London.

- Newton, A. 1896. A Dictionary of Birds. Black. London.

- Russell, G. D., White, J., Maurer, G. & Cassey, P. 2010. Data-poor egg collections: cracking an important research resource. J. Afrotrop. Zool. Special Issue 77-82.

- Spottiswoode, C.N. & Stevens, M. 2012 Host-parasite arms races and rapid changes in bird egg appearance. American Naturalist 179: 633-648.

- Walters, M. 1994. Uses of egg collections: display, research, identification, the historical aspect. Journal of Biological Curation 1: 29-35.

And don’t forget the contributions of studies of egg white proteins. They contributed to systematics, geographic variation, and molecular biology.