A couple of years ago, my family and I had an early morning stopover in Frankfurt, Germany, en route to our spring bolthole in the French Pyrenees. As we stumbled bleary-eyed to the end of the passport and customs lines, a tall, burly passport control agent took us aside and rather gruffly asked me “Are you with Her Majesty’s Secret Service?” My eloquent response was “Huh?”, to which he even more loudly repeated what he had just said. Passport control agents make me nervous at the best of times, so I blurted out the only response I could think of: “No, sir, I work for Queen’s University, not the Queen. There must be some mix-up.” He scowled, then broke into a broad smile and said, “No, I am just kidding, you are in seat 007.” Who knew that border agents had a sense of humour?

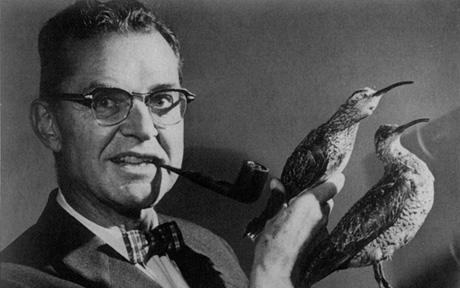

I was reminded of that incident when I read, last week, that the real James Bond—the ornithologist, James Bond—was born on 4 January 1900. The story of Ian Fleming adopting the name ‘James Bond’ for his fictional hero is well-known (see the Wikipedia link, above) so I won’t repeat it here. Instead, at least from an ornithological perspective, the real James Bond is more interesting.

In the obituary that he wrote for The Auk, Kenneth Parkes said that Bond “was a bridge between the centuries in his ornithology as in his lifespan” [1]. I interpret this as meaning his approach to ornithological collections bridged the 19th (Victorian) and 20th century approaches. I consider there to be at least 4 distinct periods of ‘museum’ work in ornithology which I would call: (1) the Curiosity period where individual natural historians maintained small cabinets of curiosity and the focus was on identification and discovery, (2) the Victorian period where large collections were most often amassed by wealthy men who were largely self-taught, and the focus was on classification based on subjective comparison of specimens, (3) the Qualitative period where those private collections moved to museums and the focus was on distributions and zoogeography, obtaining series of specimens to study the extent of within and between species variation, and (4) the present Quantitative period where museum collections are used to obtain data information about colours, shapes, sizes, and genetics of birds to test hypotheses about evolutionary change and anthropogenic influences. In many ways Bond bridged the Victorian and Qualitative periods.

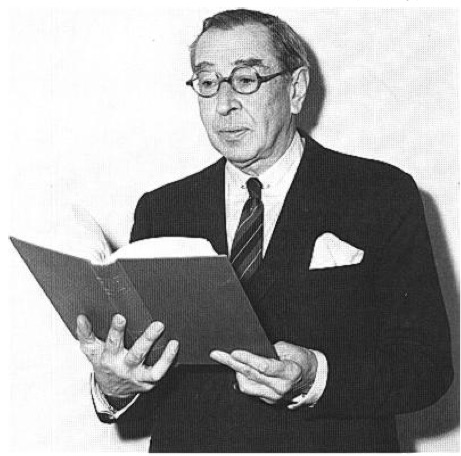

Bond grew up in Philadelphia but spent 8 years in England before graduating from Cambridge in 1922. Although he was always interested in natural history, his first job was in the foreign exchange department of a bank in Philadelphia. He quit that job in 1925 to pursue his interest in birds by joining the staff at The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. Almost right away he was to accompany Rudolphe Meyer de Schauensee on a bird collecting expedition to the lower Amazon of Brazil, from 10 Feb – 26 May 1926. de Schauensee was exactly one year younger than Bond, but was already a curator of birds at The Academy. On that expedition, they collected 500 birds and a few mammal specimens, and obtained valuable information [2] on species distributions and abundances . Even though they were outside the main part of the breeding season, they found and described the nests of several species, a topic (nidification) that became one of Bond’s life-long interests.

Many aspects of that expedition and Bond’s early career typify what I have called Victorian ornithology in that the major goals were to build up collections in museums, to learn about distributions of species, and to gather information relevant to systematic relationships among species. Bond, in particular, thought that the study of nesting habits might provide useful clues to systematic relationships. Also, like most Victorian ornithologists both Bond and de Schauensee had no formal training in science beyond an undergraduate education and worked at the museum without salary as both had independent wealth.

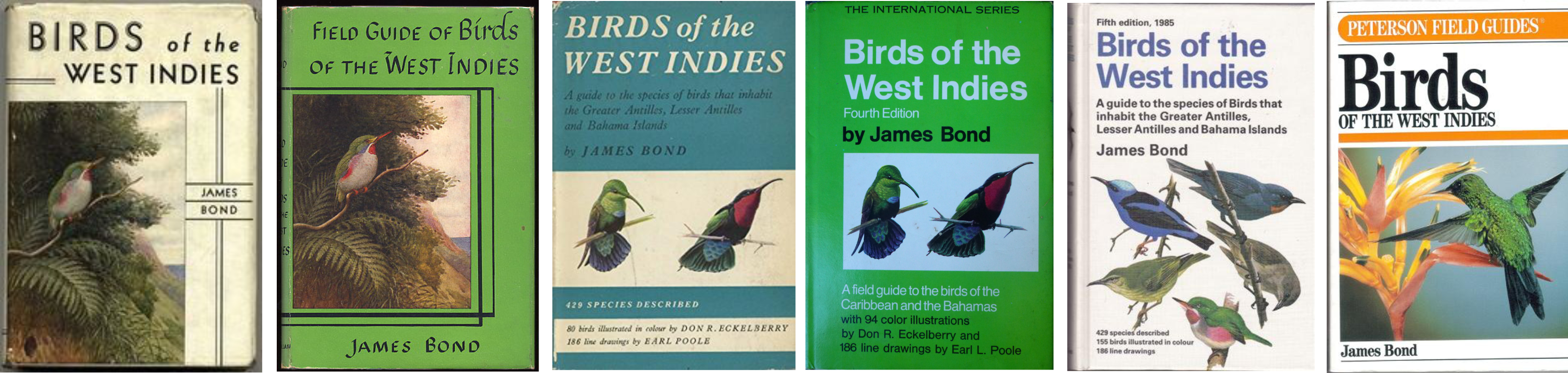

Bond is certainly best known for his work on the zoogeography of Caribbean birds, which soon became his main life-long interest. The second (1947) edition of his Field Guide to the Birds of the West Indies [3] was illustrated with line drawings by Earl Poole and the third (1963) with spectacular plates by Don Eckleberry. That guide was, of course, how the novelist and birdwatcher, Ian Fleming, came across his name while on holiday at his estate on Jamaica. Bond revised the 6th edition of his field guide just before he died and it is still—30 years later, and more than 70 years after the 1947 edition—in print and available on Amazon.

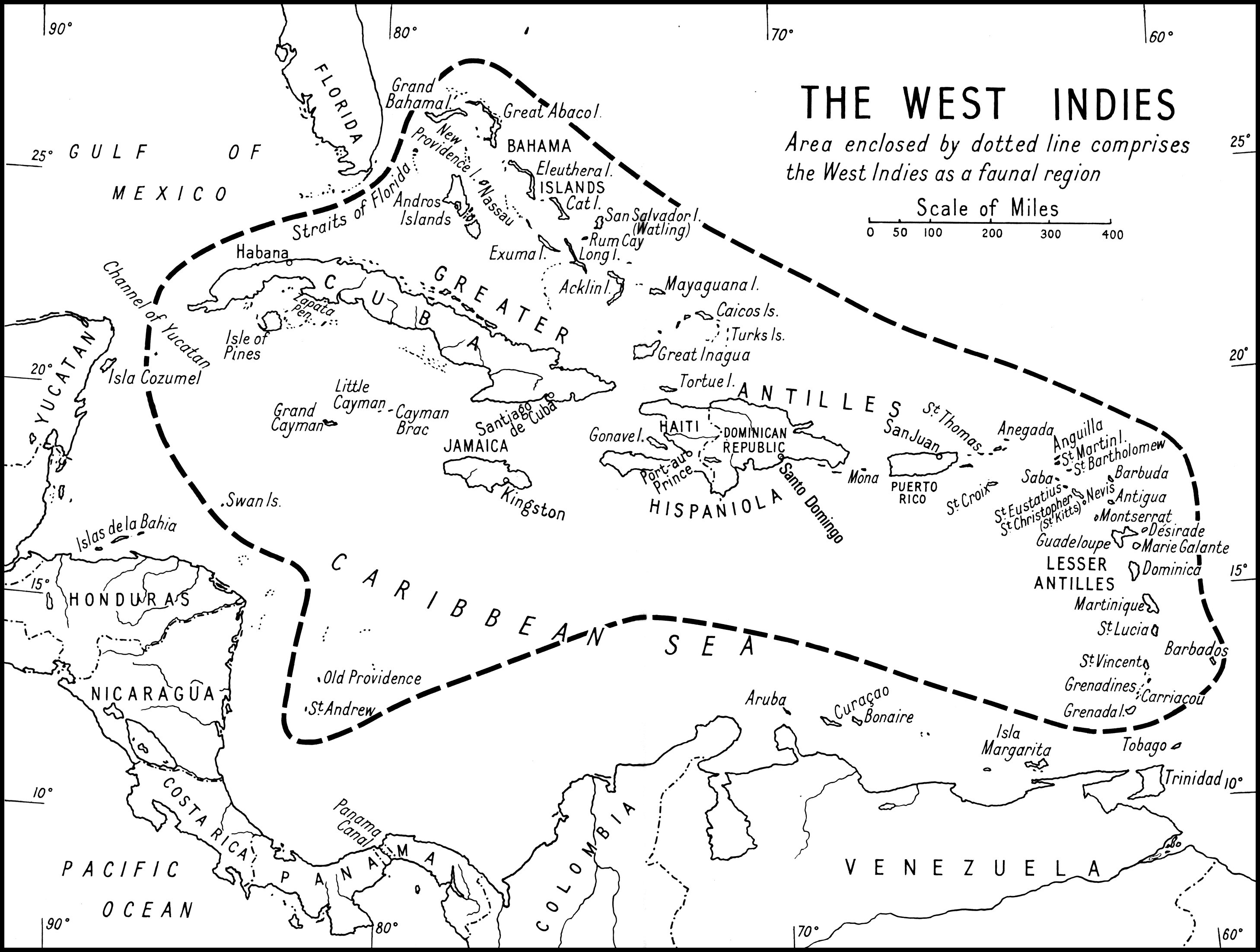

Bond’s research on Caribbean birds was more typical of the Qualitative period of museum ornithology in that he used his specimens to develop ideas about the zoogeography of Caribbean birds. David Lack once suggested to him that the avifaunal boundary that he had described between the birds of Tobago and those of the Lesser Antilles should be called Bond’s Line. Good idea!

Bond remained on the staff at The Academy for the rest of his career, publishing more than 30 papers on birds of the Caribbean islands. By the mid-1960s, he was well known as the inspiration for the name of Ian Fleming’s hero. On one of his trips to Jamaica he met Ian Fleming who gave him a copy of his novel You Only Live Twice, inscribed, “To the real James Bond, from the thief of his identity”. [4]

Before they visited Bond on Jamaica, Ian Fleming replied to a letter from Bond’s wife Mary concerning his use of her husband’s name for his swashbuckling, womanizing hero: ”It struck me that this brief, unromantic, Anglo-Saxon and yet very masculine name was just what I needed, and so a second James Bond was born. In return, I can only offer you or James Bond unlimited use of the name Ian Fleming for any purposes you may think fit. Perhaps one day your husband will discover a particularly horrible species of bird which he would like to christen in an insulting fashion by calling it Ian Fleming.” [5] It’s probably too late to expect the discovery of new and suitably horrible species of bird, but maybe we should call particularly ugly bird chicks ‘flemings’. Those of White Pelican would get my vote [6].

SOURCES

- Anonymous (1989) James Bond, Ornithologist, 89; Fleming Adopted Name for 007. New York Times, 17 Feb 1989, page D19

- Bond J (1947) A Field Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. New York: MacMillan.

- Bond J (1993) Birds of the West Indies. Fifth edition (Peterson Field Guides). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Parkes K (1989). In Memoriam: James Bond. The Auk 106: 718–720.

- Ripley SD (1986) In Memoriam: Rudolph Meyer de Schauensee. The Auk 103: 204-206

- Stone W (1928) On a collection of birds from the Para Region, eastern Brazil. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 80: 149-176

- Salvador RB, Tomotani BM (2015) The birds of James Bond. Journal of Geek Studies 2: 1-9 [accessed online 5 Jan 2019 here]

Footnotes

- quotation: from Parkes 1989 page 718

- obtained valuable information: their observations and findings were published by Witmer Stone (1928) who was, at the time, the senior scientist at the Academy of Natural Sciences, Director 1925-1928 and Curator of Vertebrates 1918-1936

- Field Guide to the Birds of the West Indies: the first edition was published in 1936 as Birds of the West Indies and Bond reverted to that title in for editions 3-6. The first two editions had no colour plates so were not in the same genre as modern field guides.

- inscription by Ian Fleming: reported in The Telegraph (UK) for 2 Dec 2008 [see here] when the book was sold at auction for £50,000

- Ian Fleming quotation: from Bond’s obituary in the New York Times (anonymous 1989)

- white pelican chicks: This suggestion was inspired by a brilliant graduate course term paper written almost 40 years ago by Bruce Lyon (now a prof at UC Santa Cruz) entitled ‘Why are baby pelicans so ugly?’

IMAGES: Bond from The Paris Review 26 Nov 2012; de Schauensee from Ripley (1986); covers from various bookseller sites; Bond Line from Bond (1993); pelican photo courtesy Bruce Lyon

Dear Bob,

Enjoyed your piece on James Bond, whom I knew at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, and whose work inspired my long-term interest and work on taxon cycles in West Indian birds. What a character he was!

Best wishes for 2019,

Bob

________________________________

Ah, as ever you are inspiring. What a great story. It is so true that in different ages people collect different kinds of data and come to different conclusions. I think we are in the eBird age.

I agree about the eBird age, and that, to me, is especially inspiring. Some people say that science is not so much about discovering truth but rather ‘truth for now’. Sometimes it bothers me to think that my discoveries are not THE TRUTH but I have come to accept that times change and the facts that I report may not be considered forever to support or reject the hypotheses they test.