By Donald Kroodsma

Related paper: Genetic analysis of Cistothorus palustris (Marsh Wren) across a broad transition zone in southern Saskatchewan reveals deep divergence and little hybridization between two cultural phenotypes by Donald E. Kroodsma, Devon Andrew DeRaad, Bruce E. Byers, Donald E. Winslow, and F. Keith Barker. Ornithology.

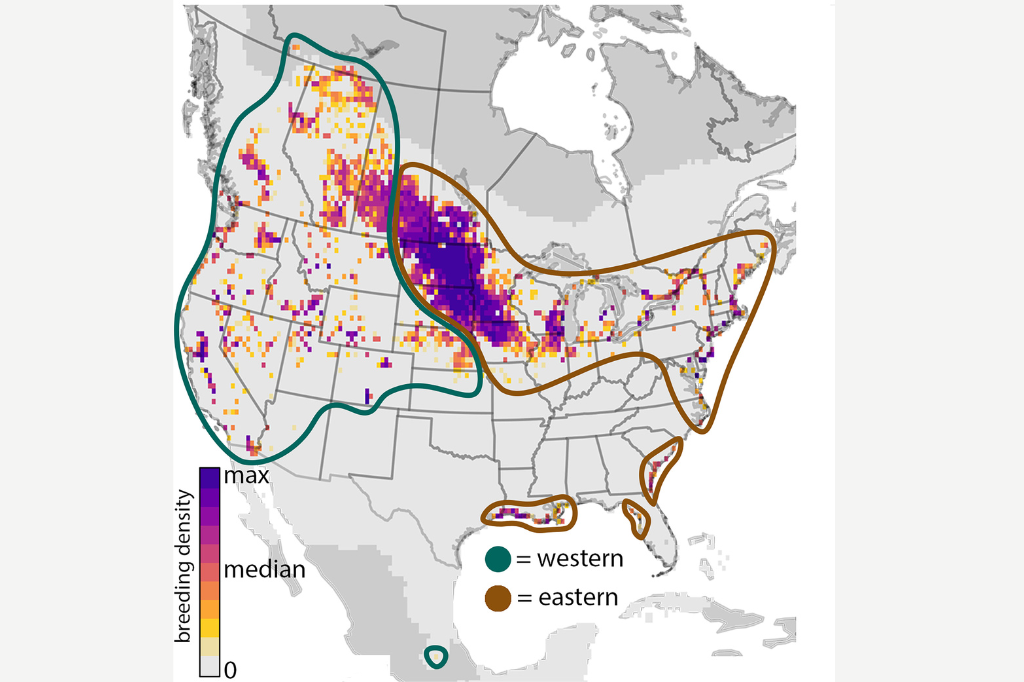

Since the late 1980s, we’ve known of an abrupt transition in Marsh Wren singing styles across the Great Plains of the United States. To the west of the transition zone, songs are harsh, grating, and highly variable, with each male having a large repertoire of up to 150 different songs. To the east, songs are semi-musical and far more homogeneous, and males learn only about 50 different songs.

Listen to the difference between these two singing styles by taking an audio tour across the continent. In the recordings linked below, you can first listen to a minute of each bird as you would hear them in the field. If you can’t hear the differences at normal singing speed (or for the simple fascination of listening to details that the birds themselves can hear), try listening to slowed-down versions of four songs from each selection. (The western and eastern males recorded in Nebraska nested side by side on adjacent territories.)

| Western | Western | Eastern | Eastern | |

| Normal songs: | Oregon-1 | Nebraska-1 | Nebraska-3 | Massachusetts-1 |

| Slowed 8x: | Oregon-2 | Nebraska-2 | Nebraska-4 | Massachusetts-2 |

Now, thanks to a > 400-km-wide zone in southern Saskatchewan where these two wrens overlap, and thanks even more to modern techniques for analyzing songs and DNA, data we collected a third of a century ago (!) reveal a glimpse of how these two wrens regard each other.

First, even though western and eastern males freely learn each other’s songs in the laboratory, in nature they rarely do, so that the cultural distinctiveness of these two Marsh Wrens is largely maintained in the overlap zone. Most of the more than 200 males that we recorded were either western or eastern singers; only a few were mixed singers that had both western and eastern songs in their repertoires. Our analyses showed that the western and eastern singers could be reliably distinguished by a key measurement of within-song variability. The measurement was larger for western males than for eastern males, with no overlap between the two groups.

Equally interesting, ancestry analysis of adult males revealed that most birds in the overlap zone are genetically either pure western or pure eastern. The relatively few birds with intermediate ancestry are first-generation hybrids or the result of recent backcrossing into a parental lineage. Conspicuously absent from our samples are birds derived from pairings between first-generation hybrids; later-generation hybrids are also rare, suggesting that strong isolating barriers prevent the two wrens from freely interbreeding.

Then, how fascinating that males of each genotype largely choose to learn the song phenotype that matches their genetic ancestry. The intriguing exceptions to this general rule were the nine mixed singers for which we had both vocal and genetic data; their ancestry ranged from 63 percent to 100 percent eastern ancestry, with six of the nine mixed singers having pure (100 percent) eastern ancestry.

Listen to these four males on territories at Nicolle Flats, Saskatchewan, Canada. From left to right: a pure western male in both songs and genes, a western singer with 100 percent eastern ancestry, a mixed singer with 100 percent eastern ancestry, and a pure eastern male in both songs and genes.

| 100% western ancestry; western singer | 100% eastern ancestry; western singer | 100% eastern ancestry; mixed singer | 100% eastern ancestry; eastern singer | |

| Normal songs: | 1_SK_Western | 3_SK_Western | 5_SK_Mixed | 7_SK_Eastern |

| Slowed 8x: | 2_SK_Western | 4_SK_Western | 6_SK_Mixed | 8_SK_Eastern |

If females choose a mate in part based on song, they can fairly reliably find the genotype of their choosing just by listening to the learned songs of a male. The relatively few mixed singers could then play an outsized role in generating the few hybrids that we find, if, for example, a genetically western female pairs with a genetically eastern male who has western songs. Perhaps our (future) analysis of the ancestries of ~170 nestlings (and the adults attending the nests) in these Saskatchewan marshes will help reveal the extent to which males and females pair and mate with others of their own genetic ancestry, the frequency of nestling hybrids, and the selective forces that help maintain the distinctiveness of the Western Marsh Wren and the Eastern Marsh Wren in sympatry.