Unpublished manuscript dated March 26th, 1918

by Lloyd Kerswill, King City, Ontario [1]

It’s nearly the end of March and I have in front of me the first issues for 1918 of the world’s major ornithological journals—The Ibis, The Auk, The Condor, The Wilson Bulletin, The Emu, and Journal für Ornithologie. Even though there are probably only a few thousand professional and amateur ornithologists worldwide, the number of scientific publications about birds has burgeoned this century. Several journals do a nice job of publishing information on some current papers, but I thought it might be useful to provide a general overview here.

Even just summarizing all of the books—let alone the scientific papers—about birds in any of the great libraries is a daunting task that may soon be impossible. I know that Messrs. William Mullens and Kirke Swann are putting together a comprehensive bibliography of British ornithology, but even that may take years to complete [2]. The AOU has almost completed a Bibliography of Bibliographies summarizing approximately 200 bibliographies including 26,000 titles and that might see publication in the next year or two [3]. The sort of listing of all ornithological publications attempted by earlier compilers, however, is probably a thing of the past.

These are trying times for humanity. The German juggernaut has just this month crossed the Somme in this endless war, and may soon occupy all of Europe. For months, now, the front page of the New York Times has been dominated by war news. I see also that there has been an outbreak of Spanish influenza in Kansas. This deadly disease is the scourge of modern medicine as it seems to appear from nowhere then sometimes spread like wildfire [4]. The AOU is taking up a collection to support our members who have gone overseas to aid in the war effort and I encourage you all to contribute to this worthy cause. The AOU will also not require that dues be paid by members in active military service [5].

As I write, the very popular Darktown Strutters’ Ball is playing on my gramophone. This catchy song was written by fellow Canadian, Shelton Brooks, who was born down in Amherstburg near Point Pelee where we go every year to watch the spectacular spring migrations. Those new musical rhythms are uplifting in this time of world tragedy, as are the ornithological journals. There’s a lot of interesting natural history being published and we should be grateful that most scientific research transcends the boundaries of nations and politics.

Here’s a brief summary of what’s in those first issues of ornithological journals in 1918 [6], in alphabetical order:

THE AUK (Jan 1918): papers and notes on species’ distributions (21), breeding biology (2), migration (1), taxonomy (2), history (1), anatomy (1), behaviour (1) plus a memorial, and notes on society business, ornithological journals, papers in other (i.e., not major ornithological) journals, publications (mainly books) received, and 18 brief notes on bird papers from the recent literature.

THE AUK (Jan 1918): papers and notes on species’ distributions (21), breeding biology (2), migration (1), taxonomy (2), history (1), anatomy (1), behaviour (1) plus a memorial, and notes on society business, ornithological journals, papers in other (i.e., not major ornithological) journals, publications (mainly books) received, and 18 brief notes on bird papers from the recent literature.

THE CONDOR (Jan-Feb 1918): papers and notes on species’ distributions (12), migration (2), anatomy (1), and behaviour (1) plus 2 brief reviews of recent books, and a note from the editor (Joseph Grinnell) on some recent papers that interested him and society news including the recent deaths of members. I like the personal touch that Grinnell adds to this journal and his insights into all things avian.

THE EMU (Jan 1918): papers and notes on species’ distributions (2), breeding biology (3, incl 1 on oölogy), and taxonomy (1), plus a memorial, some 3 letters from members on a variety of ornithological topics, and the annual report of the RAOU for 1917. That report includes details of the recent donation of H. L. White’s magnificent egg collection to the RAOU, as well as many other donations of egg and skin collections to the society. The RAOU will deposit all of these specimens in the National Museum in Sydney where they will be preserved for study and the education of future generations.

THE EMU (Jan 1918): papers and notes on species’ distributions (2), breeding biology (3, incl 1 on oölogy), and taxonomy (1), plus a memorial, some 3 letters from members on a variety of ornithological topics, and the annual report of the RAOU for 1917. That report includes details of the recent donation of H. L. White’s magnificent egg collection to the RAOU, as well as many other donations of egg and skin collections to the society. The RAOU will deposit all of these specimens in the National Museum in Sydney where they will be preserved for study and the education of future generations.

THE IBIS (Jan 1918): papers and notes on species’ distributions (1), breeding biology (3, and 2 of these on oölogy), taxonomy (1), history (1), anatomy (1), behaviour (1) plus a memorial, some notes on recent ornithological publications (including books and journals), and 7 letters from members on a variety of ornithological topics, as well as some ornithological news. One of those news items summarized the eggs presented at the Third Oölogical Dinner held in London last September where the main topic of discussion (and display) was erythristic eggs. The paper that I have categorized as ‘history’ lists all of the coloured plates published in The Ibis from 1859 to the present—a wonderful resource.

THE IBIS (Jan 1918): papers and notes on species’ distributions (1), breeding biology (3, and 2 of these on oölogy), taxonomy (1), history (1), anatomy (1), behaviour (1) plus a memorial, some notes on recent ornithological publications (including books and journals), and 7 letters from members on a variety of ornithological topics, as well as some ornithological news. One of those news items summarized the eggs presented at the Third Oölogical Dinner held in London last September where the main topic of discussion (and display) was erythristic eggs. The paper that I have categorized as ‘history’ lists all of the coloured plates published in The Ibis from 1859 to the present—a wonderful resource.

JOURNAL FÜR ORNITHOLOGIE (Jan 1918): papers on species’ distributions (4), and breeding biology (1), plus summaries of recent meetings of the Deutsche Ornithologen-Gesellschaft. The paper that I have categorized as ‘breeding biology’ is an interesting one on the effects of the war on birds.

THE WILSON BULLETIN (March 1918): papers and notes on species’ distributions (6), and breeding biology (1), plus a complete listing of the 54 women and 205 men who are currently members of the Wilson Ornithological Club, including my friend James H. Fleming of Toronto and 8 other Canadians.

From today’s perspective (March 2018)

I was surprised to find so little taxonomy in these journals as that was probably the main scientific pursuit of professional ornithologists in those days. Papers and notes on the birds of different places and regions dominated all of the journals. The Auk had the most papers and the widest diversity of topics but I found the papers in The Ibis and The Emu most relevant to my current interests in behavioural ecology. I was also surprised at both the number and quality of photographs in those journals.

I was surprised to find so little taxonomy in these journals as that was probably the main scientific pursuit of professional ornithologists in those days. Papers and notes on the birds of different places and regions dominated all of the journals. The Auk had the most papers and the widest diversity of topics but I found the papers in The Ibis and The Emu most relevant to my current interests in behavioural ecology. I was also surprised at both the number and quality of photographs in those journals.

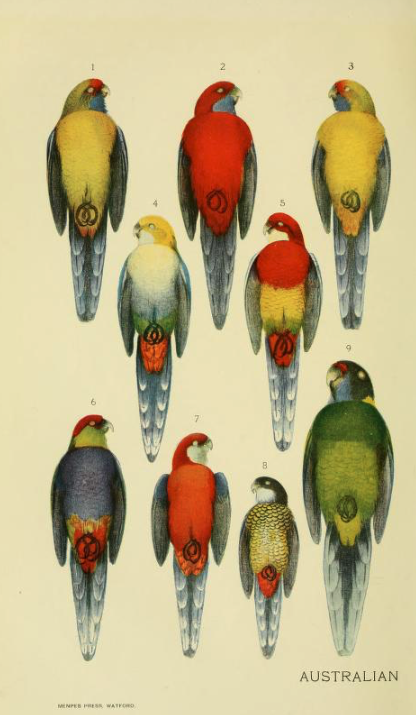

I particularly liked a paper by Gregory M. Mathews on the plumage colours of Australian Rosellas published in The Ibis, with two beautiful plates painted by the superb Danish artist Henrik Grønvold. That paper speculated on the evolution of the different colour patterns within and between species and is full of interesting insights.

Besides the science noted above, one striking thing about The Auk in 1918 is that the editor required manuscripts to be submitted to him at least 6 weeks before the publication date. That means 6 weeks from submission to print! Presumably the editor did all of the reviewing (if any) but even that is a remarkable turnaround by today’s standards.

SOURCES

-

Mathews GM (1918) The Platycercine parrots of Australia: a study in colour-change. Ibis Tenth Series Vol 6: 115-127

-

Mullens WH, Swann HK (1919) A bibliography of British ornithology from the earliest times to the end of 1912, including biographical accounts of the principal writers and bibliographies of their published works. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited.

Footnotes

1. Article from 1918: This post intended to be my (first and rather feeble) attempt at historical fiction. My idea is to try to recreate the language and feel of something written in a century ago, based on the facts available. The fictitious writer is my real maternal grandfather, Lloyd Kerswill, who did live in on the family farm in King City in 1918 (when he was 34) but he was not particularly interested in birds. He did fuel my interest in behaviour and natural history, though, and I can remember enough about him to write in his voice and to relate to some of his lifestyle on the farm, which still exists on the outskirts of Toronto. I used to listen to his ancient one-sided, shellac-based records on his wind-up gramophone in the 1950s.

2. Mullens and Swann: This work was initially published in parts, and part 6 had just been issued by Jan 1918. That turned out to be the final part so the book was put together and published officially in 1919, and a further supplement was published as a single volume in 1923.

3. Bibliography of Bibliographies: In a brief search, I can find no further mention of this work and assume that it was never published

4. Influenza: The 1918 flu pandemic eventually killed a staggering 50–100 million people worldwide

5. No AOU dues for military: see Palmer 1981 Auk 35: 70

6. Journals from 1918: back issues of The Auk, The Condor and the Wilson Bulletin are all freely available at SORA; back issues of Ibis, Emu and Journal für Ornithologie are available at the BioDiversity Heritage Library

Wonderful post as always, Bob. Regarding “only a few thousand ornithologists worldwide”, I assume you mean in 1918. Today, Auk and Condor alone have 10,000 ornithologists in its author database. So there must be tens of thousands now, if not more.

Best,

Kathleen

On Mon, Mar 26, 2018 at 5:04 AM, History of Ornithology wrote:

> Bob Montgomerie posted: “BY: Bob Montgomerie, Queen’s University | 26 > March 2018 Unpublished manuscript dated March 26th, 1918 by Lloyd Kerswill, > King City, Ontario [1] It’s nearly the end of March and I have in front of > me the first issues for 1918 of the world’s major ornitholo” >

I was afraid that that might not be clear. The entire top part of that post was meant to appear to have been written in 1918. As far as I could determine there were about 1000 members in those societies back in 1918, so I thought saying ‘a few thousand’ would be in the right ball park. As you say, there must be tens (or even hundreds) of thousands of professional and amateur ornithologists today.

Hi Bob

I was intersted by your comment on Dr. Palmer and his collection of obituaries and portraits of ornithologists. Maybe no one has had a look in his estate which is housed in the library of Congress. Maybe an interesting task for someone in the region and with interst in the history of ornithology

Kind regards

Josef

Great idea. I will make some enquiries at the upcoming AOS meeting in Tucson. Once I have finished teaching this term I will be able to spend some time on this.