Guest post by researcher Vincent Naude

Linked paper: Using web-sourced photography to explore the diet of a declining African raptor, the Martial Eagle (Polemaetus bellicosus) by V.N. Naude, L.K. Smyth, E.A. Weideman, B.A. Krochuk, and A. Amar, The Condor: Ornithological Applications 121:1, February 2019.

The Martial Eagle is one of the largest and most powerful of the booted eagles. These menacing giants dominate the skies over sub-Saharan Africa, ranging from Senegal to Somalia and down to South Africa. Their name is derived from the Latin word Martialis, meaning “from Mars,” referring to the Roman god of war—quite fitting, as these raptors are expert hunters, whether swooping in on their quarry from breathtaking heights or sitting secretly perched in the dense foliage of a tree ready to ambush. Unfortunately, a recent, rapid decline across much of their range has led to their uplisting from “Near Threatened” to “Vulnerable” on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. While it is still unclear what factors are driving this decline, evidence suggests that it may be related to their diet, specifically a reduction or shift in the availability of prey species. So, what do Martial Eagles eat, how do we measure that, and what can we do with this information?

Very little data is available on the diet of Martial Eagles. Regrettably, only three published studies exist to date, and these were conducted in South Africa in the 1980s. Traditionally, raptor diet is measured by examining prey remains or pellets at nest sites, as well as through hide watches, camera traps, and even stable isotopes. However, large eagle nests are surprisingly hard to find, and these approaches only measure diet in the breeding season. Eagles have enormous home ranges (>100km2) and nest at low densities (1 pair per 140km2), which makes studying them costly and logistically challenging.

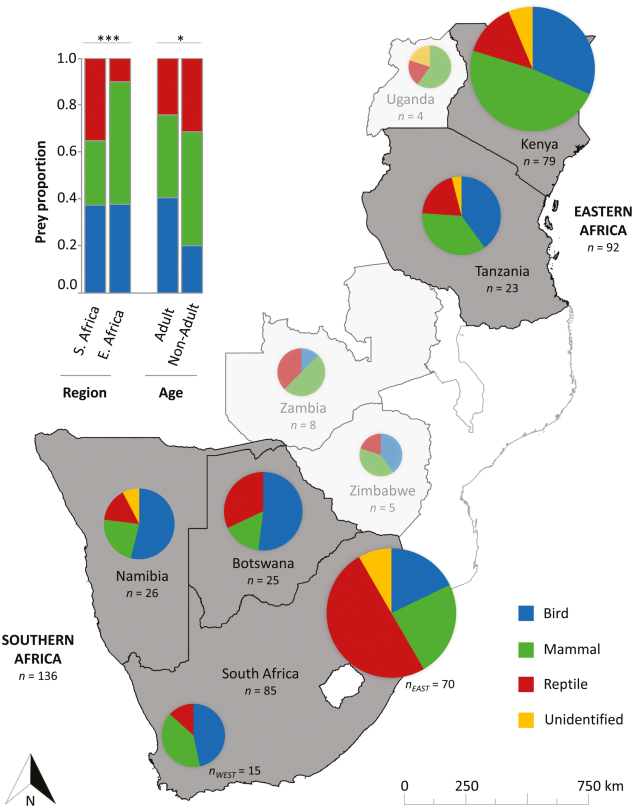

To overcome some of these challenges, we turned to a form of citizen science: using Google Images to determine Martial Eagle diet across their range from uploaded photographs. Using a specialized, open-access software platform called MORPHIC to scan Google Image results for a series of twelve unique search terms, we found 4872 photographs, 254 of which turned out to be of Martial Eagles and their prey after checking for duplication and filtering by relevance. They were taken in eight African countries between 1998 and 2016. From these photographs, we determined relative eagle age based on plumage, recorded the eagle’s feeding position, identified the prey items, and estimated prey weight.

We were pleasantly surprised to find that not only did our data agree with the only existing studies in South Africa, but it also agrees with a recently completed master’s thesis on Martial Eagle diet and behavior in the Maasai Mara of Kenya. We were able to expand on the data produced for South Africa and even reliably determine diet for four new countries.

Overall, Martial Eagles everywhere feed on the same combination of bird, mammal, and reptile prey, but the proportions of these prey types differ drastically between eastern and southern Africa. While eagles in both regions consume equal proportions of bird prey, eagles in eastern Africa rely more heavily on mammals, and those in southern Africa eat more reptiles. Martial Eagles in largely arid areas like Namibia, Botswana, and western South Africa consume mostly bird prey, whereas in wetter areas like Tanzania and Kenya, they feed more on mammals. This is obviously dependent on the relative abundance of these prey species, but the overall trends can tell us something about how dietary declines or shifts in prey numbers might be affecting these eagles. Adult eagles also consumed more bird prey than non-adults overall, which makes sense as adults are more experienced and birds are harder to catch.

Bird prey consisted mostly of guineafowl and spurfowl species, with some surprising rarities such as Spur-winged Geese, flamingos, and Kori Bustards. Antelope and small mammal species were the most frequently taken mammals, but eagles were also observed eating lion cubs, caracal, and even chacma baboons. Reptile prey included monitor lizards, a rock python, and even small Nile crocodiles.

While our study doesn’t have the fine-scale power of the nest-site surveys, we have been able accurately replicate these existing studies and provide landscape-level diet data on Martial Eagles at a fraction of the effort and cost. We hope that these new, citizen science-based and open access data approaches find a place in a conservation, as they provide new perspectives to old problems and can sometimes unveil landscape-level trends which had previously been nearly impossible to assess.