Last week I posted a list of recently published books relevant to the history of ornithology. This week I will begin to review them, one at a time, as I finish reading each one. I am a slow reader, so don’t expect me to finish before the end of the year.

This first review is about a very recent book by my friend, colleague and collaborator, Tim Birkhead, at the University of Sheffield. Tim and I have been friends for 30 years, so this review comes to you with a host of disclaimers and biases [1]. One distinct advantage of writing a book review on a blog—rather than for a scientific journal or the popular press—is that I can write in a less formal, more intimate, and ultimately, I hope, more interesting format.

So, here’s a book published in May 2018, by Bloomsbury, who have published some of Tim’s other recent books, as well as the entire Harry Potter series.

Birkhead TR (2018) The Wonderful Mr. Willughby. London: Bloomsbury

Birkhead TR (2018) The Wonderful Mr. Willughby. London: Bloomsbury

About 20 years ago, Tim wrote to me to ask who I thought was the first real ornithologist. He knew that I knew that Aristotle, Frederick II, and Aldrovandi (and others) had written about birds a long time ago, but he wanted to know who I thought had actually written about ornithology in a way that provided the foundation for development of our discipline.

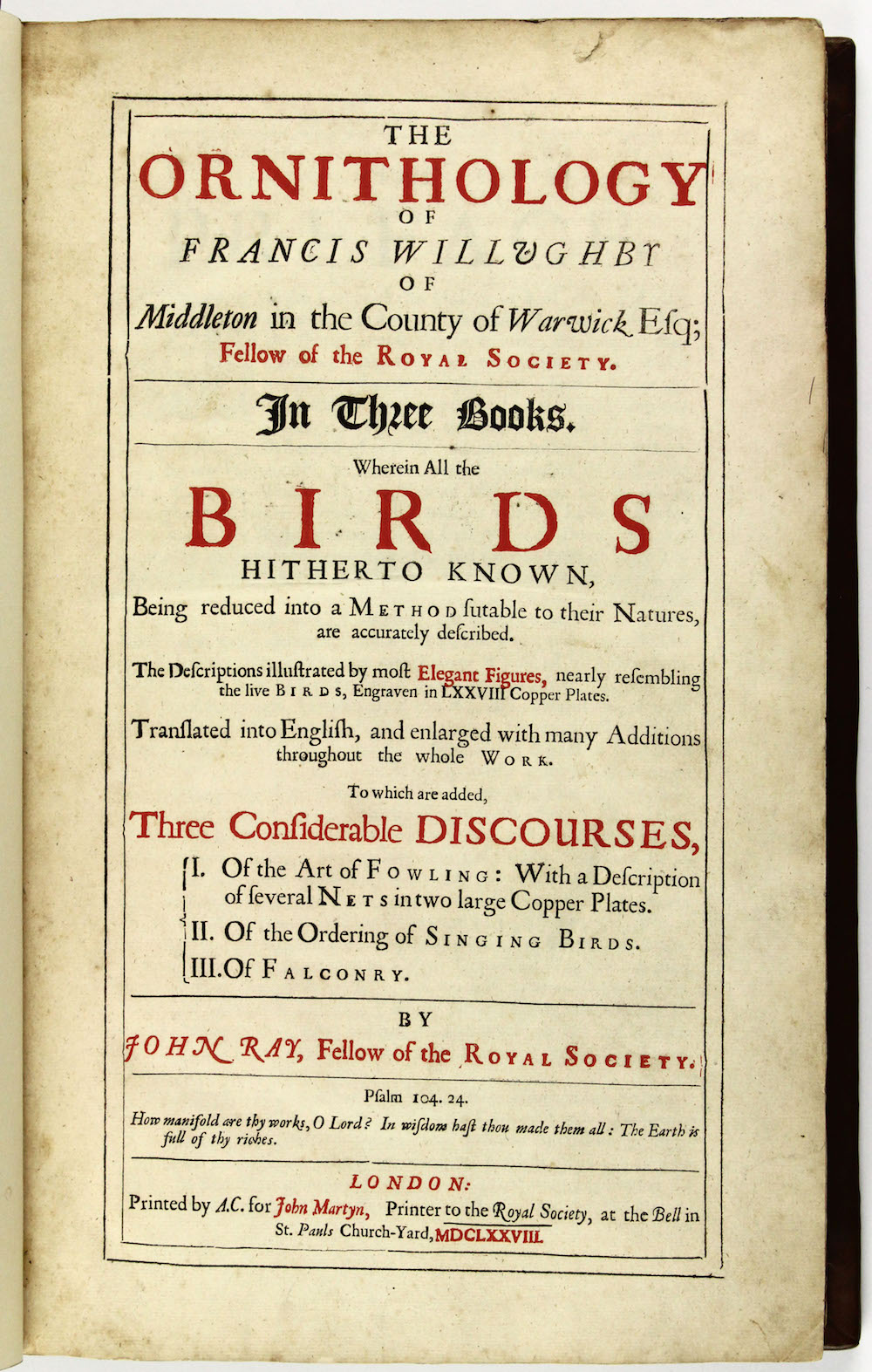

I guessed John Ray, who had written Ornithologia Tres Libris in 1676 and that was exactly what Tim was thinking, too. But I think he was more than a little surprised that I had even heard about that book.

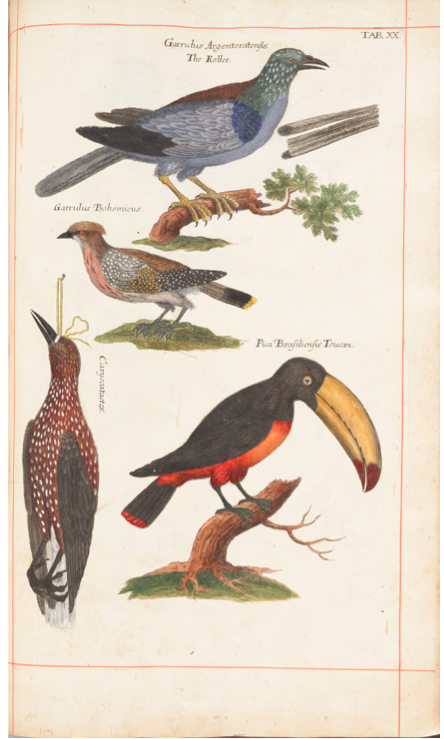

I had actually spent a couple of hours with the English edition of Ray’s Ornithologia in the rare book collection at McGill University in 1974. I started my PhD at McGill in the fall of 1973 and soon began spending every Friday morning in their fabulous Blacker-Wood Library of Ornithology and Zoology. There weren’t many of us interested in birds at McGill so I usually had the place to myself and got to know the new Blacker-Wood librarian, Eleanor MacLean, quite well. One day she asked if I’d like to see the rare book collection and that’s where I saw 3 copies of the English edition of Ray published in 1678, one of which had all the birds in colour.

When, more than 25 years later, I told Tim about this experience, he thought I must have been mistaken about the coloured edition because the book was not hand coloured. When we visited the library in 2008, sure enough both the hand-coloured book—and Eleanor MacLean—were still there. That unique copy of this book was ostensibly given to Samuel Pepys by Ray himself, and had been purchased by the library’s founder, Casey Wood, in 1922 [2].

When, more than 25 years later, I told Tim about this experience, he thought I must have been mistaken about the coloured edition because the book was not hand coloured. When we visited the library in 2008, sure enough both the hand-coloured book—and Eleanor MacLean—were still there. That unique copy of this book was ostensibly given to Samuel Pepys by Ray himself, and had been purchased by the library’s founder, Casey Wood, in 1922 [2].

Tim was convinced that Ray’s book was an under appreciated masterpiece, so he used it as the foundation for his first book on the history of ornithology *The Wisdom of Birds*, the title of which is a paean to Ray’s best-known work, *The Wisdom of God* [3].

Tim was also convinced that Francis Willugby’s contributions to the book were also under appreciated, to the point that Willughby was virtually unknown, and largely ignored in the history of science in general and ornithology in particular. Willughby and Ray were friends and collaborators but Willughby died when he was only 36, before he had published anything about birds, leaving Ray to write up his research on natural history, comprising books about birds, fishes and insects based on their 20 years of study and exploration focussed on natural history.

Ray published the Latin edition of the book giving full credit to Willughby’s contributions in the preface, but—possibly feeling a bit guilty—put Willughby’s name in the title of the English edition The Ornithology of Francis Willughby.

In retrospect that title says it all to me—this is Francis Willughby’s contribution to ornithology, written by his collaborator John Ray after Willughby’s untimely death. Many others seemed to have missed that point, Tim told me, giving full credit to the ‘genius’ John Ray and relegating Willughby to the dustbin of history.

In 1943, the Reverend Charles Raven seemed to have put the final nail in Willughby’s coffin with his detailed and fawning biography of Ray, largely dismissing Willughby as a helper who died before he could make any useful contribution.

To learn more about the relatively unknown Willughby, Tim secured funding from the Leverhulme Trust (UK) to assemble an international coterie of scholars with expertise in the life, times and interests of Francis Willughby. The first product of that collaboration was a scholarly, edited volume on Willughby pulling together all of the known facts [4]. Even though Willughby’s notebooks and archives have largely disappeared in the almost 350 years since he died, there was much to be learned, and that volume is comprehensive. Tim’s new book is based on that project, bringing Willughby to life for a more general audience, and much, much more.

Willughby and Ray met at Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1653, where the 18-year-old Willughby was a student and Ray—some 8 years his senior—was his tutor. They seemed to hit it off right away as they shared a passion for natural history and became friends despite the large gap in their social status—Willughby was wealthy and Ray a poor blacksmith’s son. Together they explored the local area with the occasional trip farther afield in southern England, with Ray focussing on botany and Willughby on zoology. But general ideas about natural history, the demarcation and identification of organisms, and thoughts about how to group them logically were their common ground.

Willughby and Ray met at Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1653, where the 18-year-old Willughby was a student and Ray—some 8 years his senior—was his tutor. They seemed to hit it off right away as they shared a passion for natural history and became friends despite the large gap in their social status—Willughby was wealthy and Ray a poor blacksmith’s son. Together they explored the local area with the occasional trip farther afield in southern England, with Ray focussing on botany and Willughby on zoology. But general ideas about natural history, the demarcation and identification of organisms, and thoughts about how to group them logically were their common ground.

With the encouragement and assistance of several friends, Willughby and Ray sought to develop a universal language of words and symbols to describe any organism [5], to compile a description of all of the known species in several large groups [6], and to formulate a classification system that would group together similar species in a hierarchical fashion [7].

On completing their studies at Cambridge, they, and two friends, embarked on a long tour of Europe, starting in the Low Countries. Travelling on foot, horseback, and, presumably, horse-drawn carriage, they gradually worked their way through Germany, Italy and Spain, before returning home. Along the way they explored woodlands, fields and waterways, haunted local markets for exotic species, visited learned naturalists and inspected their collections, and bought drawings and paintings of animals and plants whenever they could. They returned to England [8] with a treasure trove of material and set to work right away to get it organized with a goal to publish on each major grouping.

When Willughby died in 1672, they still had not written anything publishable, but they must have been close to putting pen to paper. Ray immediately began preparing a book on ornithology based on Willughby’s notes and ideas. Willughby, for example, hit on the idea that each species must have distinctive ‘characteristic marks’ that could be used to identify it conclusively, years before Roger Tory Peterson used this principle in his wildly successful series of field guides. I assume that Ray started with birds as a memorial to his friend and benefactor’s too-short life. Within two years of publishing the original book in Latin, he produced an expanded English edition, presumably to reach a wider audience, and, this time, giving proper credit to Willughby in the title. Among his many other works, Ray eventually wrote up Willughby’s notes on the fishes and insects as separate books, both in Latin and both only acknowledging Willughby’s help, as he had in the Latin Ornithologia.

To make the best of the limited information available on Willughby, and to make his new book more interesting and accessible, Tim infuses the text with his own experiences that parallel Willughby’s. Like Willughby, Tim dissected some of the same birds so that he could see first-hand what Willughby must have experienced. Tim has also been to many of the places where Willughby travelled both in England and Europe, read many of the same books, and studied many of the same birds in the field. In a few places he describes some of Willughby’s experiences in an attempt to recreate Willughby’s voice and experience—in essence, being Francis Willughby—to enliven the text. The result—history, biography, ideas and birds—is, in a word, wonderful.

SOURCES

- Birkhead TR (2008) The wisdom of birds: an illustrated history of ornithology. London: Bloomsbury.

- Birkhead TR, editor (2016) Virtuoso by Nature: The Scientific Worlds of Francis Willughby FRS (1635-1672). Leiden: Brill

- Birkhead TR, Charmantier I, Smith PJ, Montgomerie R. (2018) Willughby’s Buzzard: names and misnomers of the European Honey-buzzard (Pernis apivorus). Archives of Natural History 45: 80-91.

- Montgomerie R, Birkhead TR. 2009. Samuel Pepys’s hand-coloured copy of John Ray’s ‘The Ornithology of Francis, Willughby’ (1678). Journal of Ornithology 150:883-891.

Footnotes

1. disclaimers and biases: as Tim developed this project we discussed it often and I read some bits of the manuscript for him as the writing progressed. We also wrote two papers Germaine to the topic (Montgomerie and Birkhead 2009, Birkhead et al. 2018) but I was not part of the Leverhulme Trust project nor had I seen most of this book before beginning to read it about a month ago.

2. hand-coloured edition: see Montgomerie and Birkhead (2009) for more details

3. Wisdom of God: this is considered by many (non-biologists) to be Ray’s most important work, in which he interprets the natural world as evidence of God’s design. Such an interpreation was the goal of natural philosophy in the 1600s and Ray might well be considered to be the finest example of that approach

4. edited volume on Willughby: see Birkhead (2016)

5. universal language of natural history: they were encouraged in this endeavour mainly by their friend John Wilkins, but like the much later attempt by others to invent a universal language—Esperanto—this was a complete failure and they soon abandoned the idea, much to our benefit today.

6. descriptions of species: they focussed largely in birds, fishes, insects and flowering plants. There existed previous descriptions (Aldrovandi, Belon, etc) but these tended to be of local fauna, were mainly focused on external features, and could rarely be used for positive identification. Willughby and Ray, on the other hand, recognized that internal anatomy, habitats, song, and behaviour could all be used to distinguish species.

7. classification systems: while still crude by today’s standards, Linnaeus acknowledged their work in developing his own enduring system a century later. Willughby and Ray, for example, started by dividing all birds into land birds and water birds, then within each group made smaller grouping based on bills, feet, internal anatomy and size.

8. returned to England: Willughby returned to the family estate at Middleton Hall, and provided the funds for He and Ray to devote full time to their natural history work, even after Willughby died.

And F Willughby gets a mention early on in our ‘Catesby’ volume (pg 12 ). Guys trying to figure out what dieversity is all about and what it means. It’s great fun and I will get Tim’s book.

Cheers,

Alan