Guest Post Karl Schulze-Hagen, Mönchengladbach, Germany

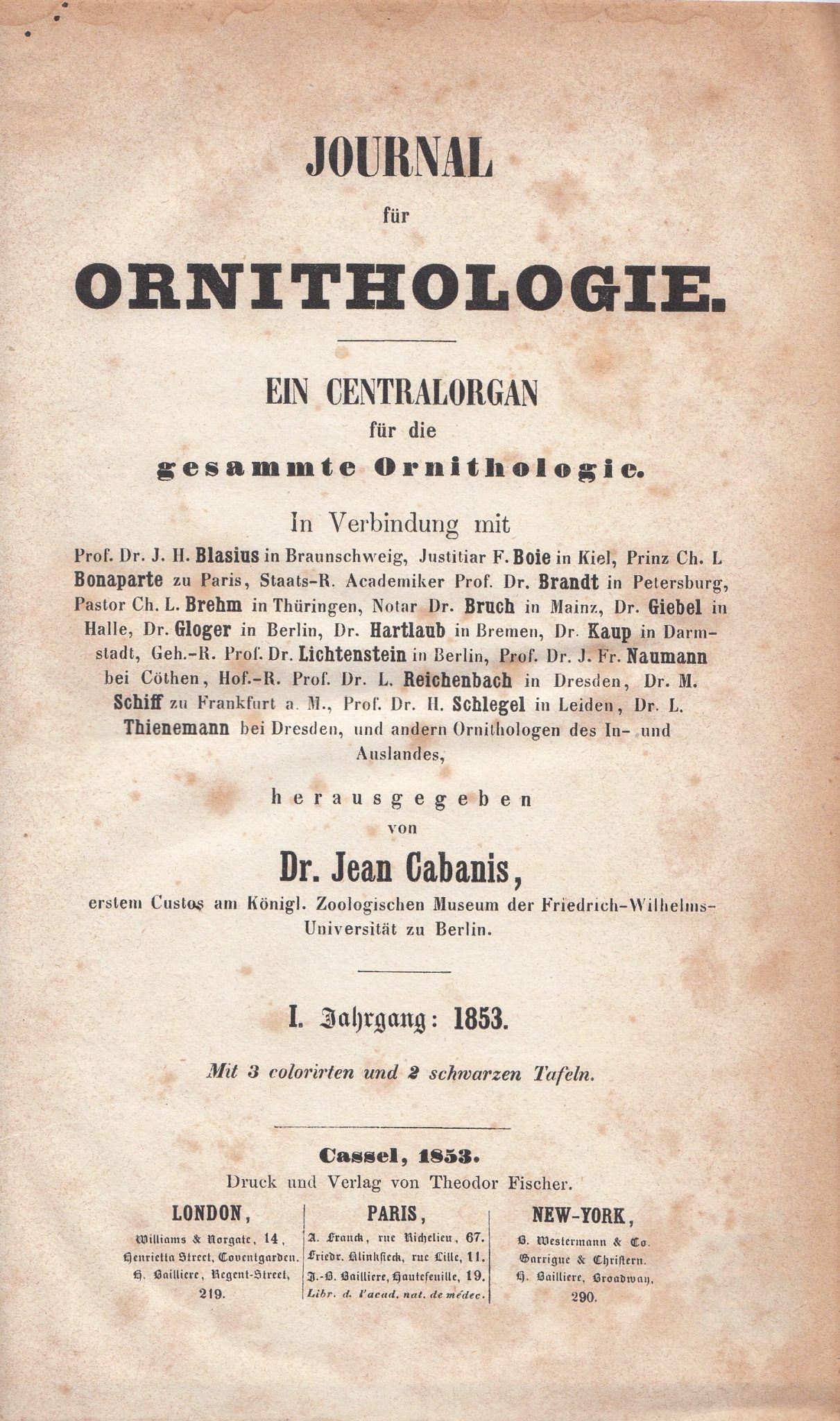

The very first paper published in the Journal für Ornithologie, in 1853, was written by the Dresden zoologist Ludwig Reichenbach (1793-1879). That paper {On the concept of species in ornithology} [see footnote 1] is a bit long-winded and difficult to comprehend by today’s standards, but it is historically important because it was the seed around which a newly formed society for the natural sciences—the Deutsche Ornithologen-Gesellschaft (DO-G)—would crystallize. The DO-G {German Ornithologists’ Society} was the first scientific ornithological society and one of the first taxon-based scientific societies world-wide.

The very first paper published in the Journal für Ornithologie, in 1853, was written by the Dresden zoologist Ludwig Reichenbach (1793-1879). That paper {On the concept of species in ornithology} [see footnote 1] is a bit long-winded and difficult to comprehend by today’s standards, but it is historically important because it was the seed around which a newly formed society for the natural sciences—the Deutsche Ornithologen-Gesellschaft (DO-G)—would crystallize. The DO-G {German Ornithologists’ Society} was the first scientific ornithological society and one of the first taxon-based scientific societies world-wide.

Following the example of entomologists and conchologists, the German ornithologists wanted to found their own society and publish a journal of their own. Before they could publish a journal, however, they wanted to have clear definitions and rules for their field of endeavour [2]. The dominant question of the day was, “What is a species?”. This controversial subject had been debated constantly in Germany since 1822, when the Gesellschaft Deutscher Naturforscher und Ärzte {Society of German Naturalists and Physicians} was founded. The meetings of that society provided the German ornithologists with an opportunity to exchange ideas.

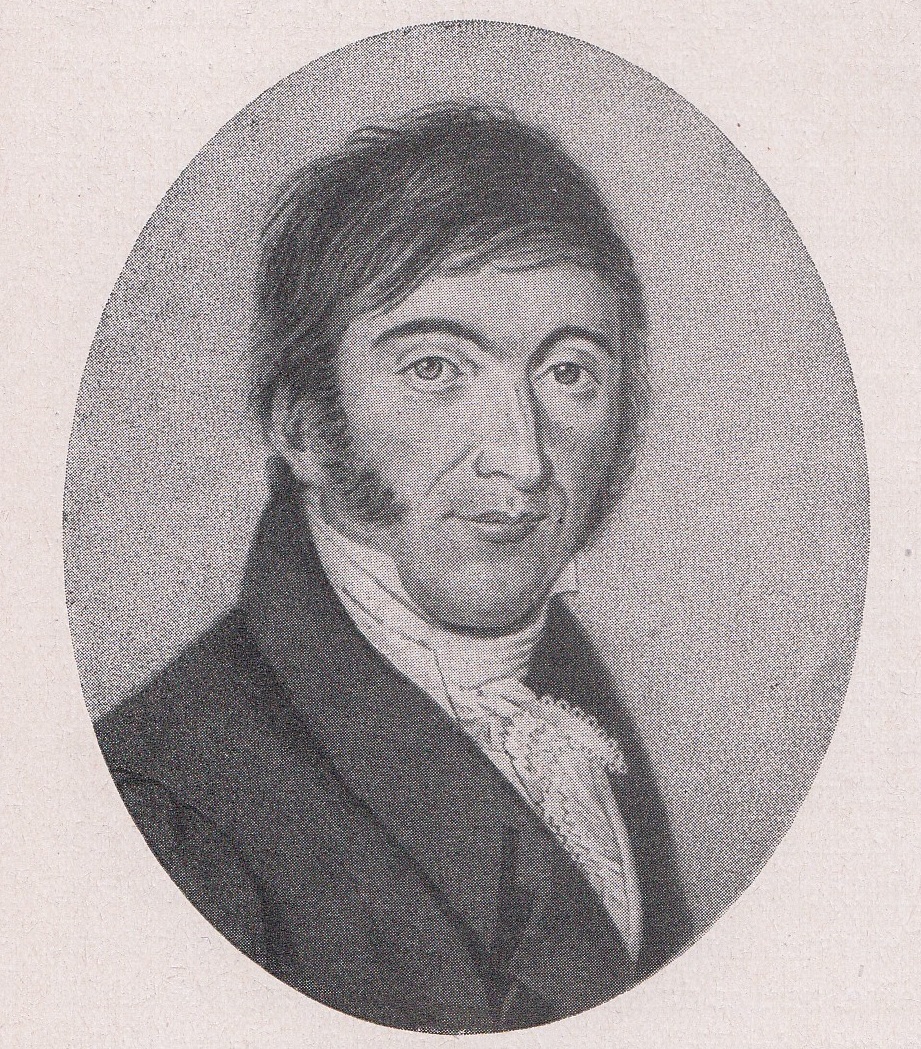

Almost a quarter of a century passed before those ornithologists could finally gather for their own meeting—in 1845—in the small town of Köthen in central Germany. But why Köthen? In the neighborhood of this rural Residenzstadt—where the local aristocratic rulers had their residence—lay the modest farmstead of the autodidact Johann Friedrich Naumann (1780-1857). Naumann’s 12-volume Naturgeschichte der Vögel Deutschlands {Natural History of the Birds of Germany} had just been completed the previous year. At over 7000 pages and 337 plates, it was then the world’s most complete description of a

regional fauna. This gigantic work “{gave the impulse to the existing but scattered forces of German ornithology to finally come together. Everywhere the work encouraged others to further research}” [3]. It was Naumann who urged “{a meeting with a few friends of ornithology}” [4]. So Naumann became the spiritus rector of German ornithology, and it was in his honor that its first assembly was held in Köthen. Presumably due to the political turbulence of 1848 in Germany that it wasn’t until 1850 that the DO-G was finally constituted, in Leipzig, with Naumann as its first President.

The production of a dedicated journal for the DO-G proved troublesome. An earlier German ornithological journal, Rhea, edited by F. A. Ludwig Thienemann (1793-1858), ceased publishing in 1848 after only two issues. This was followed by another short-lived bird journal, Naumannia, produced in 1849 by Eduard Baldamus (1812-1893), an energetic and passionate Naumann admirer. It was to be a further four years before the first issue of today’s Journal für Ornithologie (JfO) appeared, under the editorship of Jean Cabanis (1816-1906).

In the JfO’s volumes, now spanning 158 years, the historical development of ornithology can be traced. On the first page of that first issue, the future framework was established in a Prospectus: “{In as varied a diversity as possible …. treatises dealing with the entire range of ornithological subjects will be published, including paleontology and physiology. Specific and general ornithology, systematics and oology. ….. Monographs, description of new species, faunas, geographical distribution, and life histories, including consideration of the mental [‘psychisch’ in German, literally ‘of the soul’!] capabilities of birds}”. [3]

From the very beginning, German ornithology consisted of two strands: taxonomy or systematics, and avian biology. Perhaps surprisingly, both subdivisions of the field were given equal space in the Journal—while the first volume began with an article outlining a basic definition of ‘species’, it ended with two contributions from Constantin Gloger (1803-1863)—one on host-species choice in the Cuckoo and the other on interspecific copulation in ducks.

But the problem troubling all ornithologists of the day—the question of what a species is—remained unresolved. The 10th DO-G conference, in 1856 and again in Köthen, revolved around this conundrum alone [5]. For several days Naumann, Christian Ludwig Brehm (1787-1864), Baldamus, Gloger, Charles Lucien Bonaparte (1803-1857) and other colleagues debated the topic. Finally they agreed on a provisional definition: “{Individuals forming a community on the basis of common descent or for the purpose of reproduction can be regarded as belonging to the same species.}“ [3]

In 1856, Darwin’s On The Origin of Species had yet to appear in print. Neither was it foreseeable that a century later Ernst Mayr (1904-2005)—an ornithologist and evolutionary biologist who grew up in Germany but worked in the USA—would have a lasting influence on our current thinking with his own biological species concept.

SOURCES

- Cabanis J (1853) Prospectus. Journal für Ornithologie 1: 1-4.

-

Naumann JA (1820-1844) Naturgeschichte der Vögel Deutschlands: nach eigenen Erfahrungen entworfen. 12 volumes. Leizig: G. Fleischer.

- Reichenbach L (1853) Über den Begriff der Art in der Ornithologie. Journal für Ornithologie 1:5–15.

- Schalow H (1901) Ein Rückblick auf die Geschichte der Deutschen Ornithologischen Gesellschaft. Journal für Ornithologie 49: 6-25.

FOOTNOTES

- quotations and titles enclosed in curly brackets {} are English translations of the original German

- see Cabanis (1853)

- quotation from Schalow H (1901)

- quotation from Bezzel E (1988) Die Vesammlungen deutscher Ornithologen 1845-1987: Ein Streifzug durch die Geschichte der Deutschen Ornithologen-Gesellschaft. Journal für Ornithologie 129. Sonderheft: 2-21.

- see Schalow (1901)

Karl Schulze-Hagen, MD, is a member of the Advisory Committee of the DO-G. He has written extensively about birds and the history of ornithology, and is coauthor (with Bernd Leisler) of a book on the European reed warblers. Their Reed Warblers: Diversity in a Uniform Bird Family was published in 2011 by KNNV Publ. (available from Amazon here) and won the BB/BTO Best Bird Book of the Year award in 2012.

Karl Schulze-Hagen, MD, is a member of the Advisory Committee of the DO-G. He has written extensively about birds and the history of ornithology, and is coauthor (with Bernd Leisler) of a book on the European reed warblers. Their Reed Warblers: Diversity in a Uniform Bird Family was published in 2011 by KNNV Publ. (available from Amazon here) and won the BB/BTO Best Bird Book of the Year award in 2012.

COMMENTS