Post updated on 14 May 2024, to add Harris’s Sparrow to the list of extant species with eponymous English names whose regular breeding and nonbreeding ranges occur entirely within the U.S. and Canada or nearly so. Post updated 23 September 2024 to correct image caption.

In an effort to address past wrongs and engage more people in the enjoyment, conservation, and study of birds, the Council of the American Ornithological Society (AOS) announced a decision in November 2023 to change all English common bird names within its geographic purview that are currently named directly after people (eponymous names), as well as other names deemed offensive and exclusionary. The AOS Council decided to establish a diverse, new committee to oversee this work and to involve the public in the process of selecting new English common bird names. The AOS leadership has been working diligently since that decision to determine the best way to carry out these commitments, which entail a marked change from how name changes have been handled in the past. Since the announcement, there has been an outpouring of both supportive and critical reactions from our members and the public, showing the multiplicity of feelings around the issue. We realize that the Council’s decision came as a surprise to many people, and we have received feedback questioning its scope, both from our members and from the broader ornithological community. This message is the first of many future communications that will help explain the background behind the decision, the complexities involved in adopting a new naming process, and the progress of the project to date.

Background of the Decision

The American Ornithological Society (AOS) and one of its predecessor societies, the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU), have long been recognized as the taxonomic and nomenclatural authority for maintaining a standardized list of the scientific and English common names for all species of birds found in North America, ever since it published the first Check-list of North American Birds in 1886 (hereafter Check-list; AOU 1886, Winker 2022). The AOS’s North American Committee on Classification and Nomenclature (otherwise known as the North American Classification Committee or NACC) maintains the Check-list, whose geographic coverage now includes continental North America, Middle America (Mexico through Panama), Hawaiʻi, and the West Indies (Winker 2022).

During the past several years, the AOS has been engaged in discussions, forums, and decisions about how best to handle eponymous and other English common bird names that may be perceived as offensive or exclusionary. The NACC first changed an offensive English common name, unassociated with a change in the scientific name, in 2000 (changed to the Long-tailed Duck from an offensive term for an Indigenous woman; AOU 2000). In 2019, the NACC formally revised its policy to allow vernacular names perceived as derogatory or otherwise offensive to be changed on a case-by-case basis (AOS NACC 2020). In 2020 the NACC renamed one eponymously named species to the Thick-billed Longspur, which had previously been named after an individual who served at the rank of major general in the Confederate Army during the U.S. Civil War (Chesser and Driver 2020). That same year, the AOS leadership was presented with a public petition initiated by a group called Bird Names for Birds with over 2,500 signatories requesting the AOS to change all English eponymous names of birds, rather than to consider changes on a case-by-case basis, as had been the traditional practice. In 2020 and 2021, a subcommittee of the AOS Diversity and Inclusion (D&I) Committee conducted several listening sessions about eponymous English common bird names with scientists, birders, educators, and other representatives from the ornithological community and then hosted a public discussion on the name change process (Liu et al. 2024). In 2022, the AOS leadership constituted the Ad Hoc English Bird Names Committee (EBNC) with the following charge: to develop a process that would allow the AOS to change harmful and exclusionary English bird names in a thoughtful and proactive way for species within the purview of the AOS. The EBNC presented their final report and recommendations to the AOS Council in August of 2023 (AOS EBNC 2023).

After reviewing the EBNC’s report and discussing it in depth, the AOS Council (2023) announced on 1 November 2023 three important commitments relating to the English common names of birds: (1) to change all English-language names of birds within its geographic purview that are named directly after people (primary eponyms), along with other names deemed offensive and exclusionary, focusing first on those species that occur primarily within the U.S. or Canada; (2) to establish a new committee to oversee the assignment of all English common names for species within AOS’s jurisdiction; and (3) to actively involve the public in the process of selecting new English bird names.

The objectives of the Council’s commitments are not only to change harmful English names but also to develop a more inclusive process for identifying new names. Stated goals behind this decision are to remove exclusionary barriers to participation in the enjoyment of birds and to educate the public about the birds themselves, their recent population declines (cf. Rosenberg et al. 2019), and their critical conservation needs.

Recent Responses to the Decision

Since we publicly announced the decision last November, the AOS has received a wide range of supportive and critical feedback both in the news media and in direct correspondence. Hundreds of national, international, and local news sources disseminated stories about the AOS’s commitment, including articles in major sources such as The New York Times, the The Washington Post, National Public Radio, USA Today, and the Associated Press, and the Wilson Ornithological Society released a public statement in support of the AOS’s decision. Based on an informal evaluation of social media and email responses to the AOS in the first two months after the announcement, general reactions fit into several themes:

- Supportive feedback that this is the right thing to do, will be more welcoming and inclusive, and will put the focus on birds rather than on people.

- Neutral responses or questions, which often included suggestions for new names for specific species or questions about timelines and processes.

- Criticism that this decision was too broad and would promote taxonomic instability, waste resources, and erase history.

- Criticism over a perceived lack of an open and democratic process for making decisions.

In March 2024, the AOS received a formal public petition to reconsider the decision to change all eponymous names and instead return to the previous case-by-case method for removing offensive names. This petition had almost 6,000 signatories when submitted. In early April 2024, the AOS received a formal resolution signed by 231 AOS Fellows and Honorary Fellows requesting that the AOS “defer on replacing all eponymous names until a more inclusive approach is undertaken to inform the decision to remove all eponymous names.” The authors encouraged us to proceed with the proposed pilot project to change an initial set of names (see update below) but requested that we then engage in a thorough and open discussion with AOS members about the matter, solicit input from the general public and other ornithological societies, and conduct a formal poll of AOS members about the decision. The AOS Fellows also requested a forum to discuss the decision at the upcoming AOS Annual Meeting in Estes Park, Colorado, in early October 2024.

The announcement of the AOS’s decision to change eponymous names has also spurred additional important conversations about the responsibility for English common bird names outside of North America. The AOS Council statement on changing English bird names acknowledged the need to work with ornithological societies in Central and South America to determine which organizations would be the most appropriate stewards of English common names in these regions. Our decision to change all eponymous English names of birds within our geographic purview triggered a marked response from the AOS’s South American Classification Committee (SACC), which has maintained the globally recognized checklist of South American birds since 1998. The SACC had been formally affiliated with the AOS since 2002, but after the AOS announced its decision to change all eponymous names, almost all members of the SACC joined the International Ornithologists’ Union (IOU) as a regional committee within the IOU’s Working Group on Avian Checklists, whose goal is to produce and maintain a global checklist of birds. This change in affiliation has resulted in an additional complexity relative to our decision, namely, the need to discuss and decide with other checklist committees and ornithological societies what is truly within the AOS’s geographic purview for naming (and renaming) birds. The AOS is committed to engaging in such collaborative discussions and efforts.

Geographic Purview and Other Complexities

The 2023 Check-list of North American and Middle American birds includes 2,186 species (Chesser et al. 2023). It is important to understand that, although the AOU (and now AOS) has been long recognized as the authority on the scientific and English common names of these species, this authority is not legally conferred nor guaranteed. Rather, this authority has been granted by others through common recognition of the expertise of members of the NACC and respect for their decisions regarding avian taxonomy and nomenclature. The standard practice for NACC has been to make decisions about taxonomy and names only for those species that occur primarily in North or Middle America or both. Decisions about species with broad geographic distributions across the Americas have been decided either jointly by the NACC and SACC or through a consensual agreement for one to defer to the other’s decision. The NACC has generally deferred to other authorities (regional or global checklist committees) for species whose primary breeding and nonbreeding ranges occur elsewhere.

On the NACC Check-list (Chesser et al. 2023), there are currently 150 species of birds with primary eponyms (e.g., Clark’s Nutcracker and Montezuma Quail; see Appendix for scientific names). About half of the species with eponymous names have significant breeding ranges in the U.S. and Canada. Many of these, however, spend most of the year in Mexico, Central America, or South America and only come north for two to three months to breed (e.g., Baird’s Sandpiper, Swainson’s Thrush). Some of these have broad Arctic breeding distributions and occur elsewhere across the globe during the nonbreeding season (e.g., Steller’s Eider, Ross’s Gull). Among the other half of the species are many that are endemic to Mexico or Central America (e.g., Sumichrast’s Wren, Canivet’s Emerald) or that breed and winter primarily outside of the Americas and are only on the NACC Check-list due to peripheral occurrence in the region (e.g., Temminck’s Stint, Zino’s Petrel). There are only eight extant species with eponymous English names whose regular breeding and nonbreeding ranges occur entirely within the U.S. and Canada or nearly so: Clark’s Nutcracker, Smith’s Longspur, McKay’s Bunting, Bachman’s Sparrow, LeConte’s Sparrow, Nelson’s Sparrow, Harris’s Sparrow, and Henslow’s Sparrow. The range of a ninth species, the Barrow’s Goldeneye, is largely restricted to these two countries, but a small, disjunct population breeds in Iceland.

These geographical considerations highlight the importance and complexities of working with other checklist committees and ornithological societies throughout the species’ ranges when making naming decisions. Clearly, the AOS needs to initiate discussions on eponymous English common bird names with our international partners for the species that we share and to determine the best way to engage with the diverse public users of English names throughout the species’ ranges when making any name changes.

Pilot Project and Next Steps

The AOS is moving forward with a pilot project to determine new English common names for an initial set of six species of North American birds. A new ad hoc committee will be appointed to oversee this pilot project, vested with the charge of further developing and testing a new process for determining the replacement names for these six species. The core AOS committee will have expertise in ornithology, taxonomy, and nomenclature as well as experience in communications and social science. This core committee will work closely with an internal AOS working group, including members of the AOS’s NACC, D&I Committee, History Committee, and Conservation Committee, as well as one or more external working groups. External working group members will include species and geographic experts, representatives of ornithological organizations and diverse stakeholder groups, and other expertise as needed. The committee will also be supported by the new AOS D&I Coordinator and other AOS staff as needed.

Key tasks of the committee and working groups will include developing partnerships for this pilot effort with ornithological checklist committees, scientific societies, birding organizations, and other interested groups throughout the species’ geographic ranges; developing a platform for engaging the public in the U.S., Canada, and elsewhere in the species’ ranges; soliciting suggestions for names and educating the public about conservation challenges; ensuring a diversity of perspectives have been sought on suitable replacement names; and following appropriate naming conventions that will ensure stability.

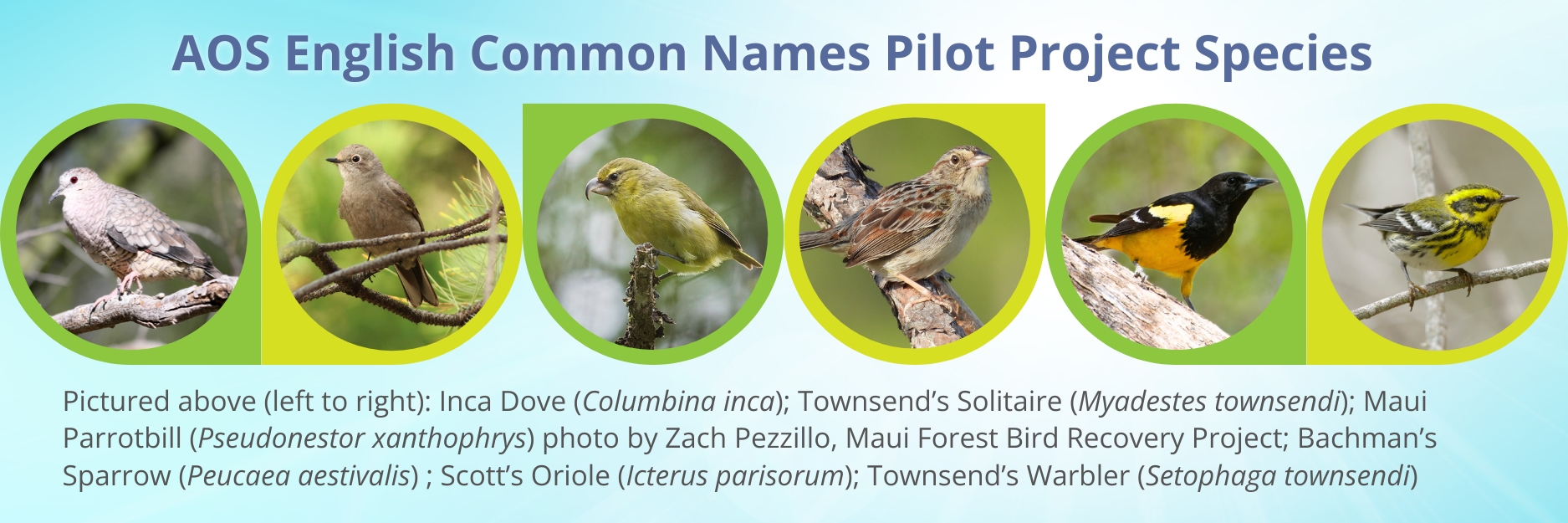

The following six species will be included in the pilot project, all of which have significant breeding ranges within the U.S. and Canada and whose English common names have all been recommended by the AOS EBNC for changing:

- Inca Dove

- Townsend’s Solitaire

- Maui Parrotbill

- Bachman’s Sparrow

- Scott’s Oriole

- Townsend’s Warbler

This group of species includes four eponymous names (Townsend’s Solitaire, Bachman’s Sparrow, Scott’s Oriole, Townsend’s Warbler); one of the three non-eponymous names recommended to be changed because they had derogatory or culturally unsuitable references (Inca Dove); and one name of an Hawaiian species (Maui Parrotbill) that had been recommended previously for changing to a local Hawaiian name (Kiwikiu), an action that would acknowledge the importance of considering Indigenous names, particularly for endemic species with limited ranges. Two of the species are year-round residents in the U.S. (Maui Parrotbill, Bachman’s Sparrow); three breed primarily in the U.S. and Canada but occur year-round regularly as far south as Mexico (Townsend’s Solitaire, Scott’s Oriole) or winter as far south as Costa Rica (Townsend’s Warbler); and the sixth (Inca Dove) is a Middle American species with a significant portion of its breeding range in the southern U.S., and not within the original range of the Inca people. The Bachman’s Sparrow is considered Near Threatened on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species and the Maui Parrotbill is Critically Endangered (BirdLife International 2024); both provide significant opportunities to educate the public about conservation challenges. All these species provide opportunities for educating the public about the need to change harmful and exclusionary English common names. At the conclusion of this pilot project, the committee will be asked to provide an assessment of how well the new structure and process worked for engaging the public and selecting the replacement names.

AOS Public Forum on English Common Names at 2024 Annual Meeting in Estes Park

The AOS will be hosting a public forum on English common names for those attending our annual meeting in Estes Park, Colorado, in October 2024. At this forum we plan to provide an update on the current status of the pilot project as well as discuss some of the topics addressed above. We invite everyone to submit suggestions for discussion topics and potential formats for the forum itself using the online form below.

Other Opportunities for Involvement

We encourage anyone who has ideas about how best to design and implement the pilot project, including engaging with the broader public throughout the target species’ ranges, to share your suggestions with AOS leadership. If you have key expertise and interest in participating in a working group for the pilot project, we also encourage you to contact us. Please use the online form below to submit your contact information and a brief summary of your expertise, interest, and ideas to us.

We encourage everyone who has an interest in North American birds, whether you’re excited about moving forward or you’re uncomfortable about the scope of the renaming decision, to participate in this pilot project and to provide constructive feedback on any aspect of it, as desired.

Once the pilot project has begun, everyone will be encouraged to submit their ideas for suitable replacement names for these six species. At the conclusion of the pilot project, we will conduct a professional evaluation of the pilot project, including a survey of AOS members and other participants about the goals, methods, and accomplishments of the project as well as suggestions for improvement.

The AOS leadership is interested in any ideas, comments, feedback, and suggestions you would like to share with us about the development of this pilot project and how you might become involved; about any AOS decisions or actions regarding English common bird names; or about the upcoming AOS public forum that will address this initiative at our 2024 annual meeting. Please submit your ideas and comments to us through this online form by Friday, 31 May 2024.

For more information about this project, please see answers to our Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ).

We appreciate your engagement in this important initiative.

AOS Executive Committee

Colleen Handel, AOS President

Sara Morris, AOS President-Elect

Matt Carling, AOS Treasurer

Sushma Reddy, AOS Secretary

Judith Scarl, AOS Executive Director

References

American Ornithological Society (AOS) ad hoc English Bird Names Committee (EBNC). 2023. Ad hoc English Bird Names Committee recommendations for Council of the American Ornithological Society (AOS). https://americanornithology.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/1-AOS-EBNC_recommendations_23_10_19.pdf

American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU). 1886. The Code of Nomenclature and Check-list of North American Birds. American Ornithologists’ Union, New York, NY, USA.

American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU). 2000. Forty-second supplement to the American Ornithologists’ Union Check-list of North American Birds. Auk 117:847-858.

Chesser, R. T., and R. Driver. 2020. Proposal 2020-S-1, Change the English name of McCown’s Longspur (Rhynchophanes mccownii). https://americanornithology.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/2020-S.pdf

Chesser, R. T., S. M. Billerman, K. J. Burns, C. Cicero, J. L. Dunn, B. E. Hernández-Baños, R. A. Jiménez, A. W. Kratter, N. A. Mason, P. C. Rasmussen, J. V. Remsen, Jr., and K. Winker. 2023. Check-list of North American Birds (online). American Ornithological Society. https://checklist.americanornithology.org/

Liu, I. A., E. R. Gulson-Castillo, J. X. Wu, A.-Ju. C. Demery, N. Cortes-Rodriguez, K. M. Covino, S. B. Lerman, S. A. Gill, and V. Ruiz-Gutierrez. 2024. Building bridges in the conversation on eponymous common names of North American birds. Ibis. https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.133320

Rosenberg, K. V., A. M. Dokter, P. J. Blancher, J. R. Sauer, A. C. Smith, P. A. Smith, J. C. Stanton, A. Panjabi, L. Helft, M. Parr, and P. P. Marra. 2019. Decline of the North American avifauna. Science 366:120–124. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw1313

Winker, K. 2022. A brief history of English bird names and the American Ornithologists’ Union (now American Ornithological Society). Ornithology 139:ukac019. https://doi.org/10.1093/ornithology/ukac019

Appendix

List of common and scientific names of species mentioned in the text.

Steller’s Eider (Polysticta stelleri)

Barrow’s Goldeneye (Bucephala islandica)

Montezuma Quail (Cyrtonyx montezumae)

Inca Dove (Columbina inca)

Canivet’s Emerald Cynanthus canivetii)

Temminck’s Stint (Calidris temminckii)

Baird’s Sandpiper (Calidris bairdii)

Ross’s Gull (Rhodostethia rosea)

Zino’s Petrel (Pterodroma madeira)

Clark’s Nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana)

Sumichrast’s Wren (Peucaea sumichrasti)

Townsend’s Solitaire (Myadestes townsendi)

Swainson’s Thrush (Catharus ustulatus)

Maui Parrotbill (Pseudonestor xanthophrys)

Smith’s Longspur (Calcarius pictus)

McKay’s Bunting (Plectrophenax hyperboreus)

Bachman’s Sparrow (Peucaea aestivalis)

Harris’s Sparrow (Zonotrichia querula)

LeConte’s Sparrow (Ammospiza leconteii)

Nelson’s Sparrow (Ammospiza nelsonii)

Henslow’s Sparrow (Centronyx henslowii)

Scott’s Oriole (Icterus parisorum)

Townsend’s Warbler (Setophaga townsendi)

“There are only seven extant species with eponymous English names whose regular breeding and nonbreeding ranges occur entirely within the U.S. and Canada or nearly so: Clark’s Nutcracker, Smith’s Longspur, McKay’s Bunting, Bachman’s Sparrow, LeConte’s Sparrow, Nelson’s Sparrow, and Henslow’s Sparrow. ” Let’s not forget about Harris’ sparrow.

Or Lewis’ Woodpecker

Thanks, Scott. We have updated our post to reflect this oversight.

I would add Newell’s Shearwater and Tristram’s Storm-Petrel.

I’m interested in all whose names have appeared as names of birds. Will you provide a list?

Or Lewis’ Woodpecker, or Barrow’s Goldeneye, and perhaps Abert’s Towhee….

I am very encouraged with this process.

Harmful? Please, leave the names alone and find a worthy cause.

PLEASE include changing all first names “Common” to something else…species are no longer “common”!

Who decided that any of these names are/were harmful? do you have any data, polls, or other information supporting this assertion? What happened to “Sticks & stones may break my bones, but names will never hurt me”?

This is a complete waste of time, energy, and money that could be better spent on preserving habitat and other more pressing conservation issues. If accepted, this proposal will NOT change history, or any perceived wrongs based on a 21st century outlook. The only thing “harmful” is what this ill-thought proposition has done to the birding community. Doesn’t the committee have better more important things to do? Stay focused on the science and leave politics out.

This initiative is encouraging if this approach will be adopted going forward. Changing the names of birds whose current names celebrate the perpetrators of apologists for racial discrimination or offensive acts such as grave-robbing makes sense, and avoids assuming that everyone after whom a bird was named was somehow complicit in such acts.

We havevery important work to do in the study and conservati0on of bird species. These activities, including current and future listing designations, depend on a name that corresponds to a taxon of concern. Anything that disrupts this, weakens our conservation efforts, does not help the species, and probably doesn’t mean anything to most birders or ornithologists. Names should be changed if there is confusion over what bird(s) the name refers to. Keeping in mind that the scientific names won’t change, YET. The AOS has the capacity and opportunity to cause chaos and confusion and could be headed in that direction.. As a birder for 75 years, learning, and sometimes unlearning names, I am opposed to the AOS taking any blanket action to destabilize the names of birds. The process of naming news taxa was both a challenge and an opportunity we should be attentive going forward. I was Okay when the “McCown’s” longspur was on the block, but suggestions to undo “Audubon” represent a disregard for our history to very little purpose. I vote for discontinuing any generic approach to renaming. I doubt whether there is any name change that could become a recruiting tool. .

In all due respect, I don’t see where AOS has proven that eponymous bird names are a hindrance or harmful to Black & Indigenous people. Nor have you proven that changing ALL eponymous bird names will make the field more welcoming to and inclusive of folks of color. The AOU was founded in 1883 now called AOS. In 141 years the field remains predominantly ‘white’’. What has been done in 141 years to change this trend? To be inclusive and welcoming? It’s very disappointing that the AOS leadership ignored the well-thought out and written ‘PETITION’ submitted last fall regarding the changing of eponymous bird names and to consider making changes on a case by case basis. What’s the hurry? You totally ignored over 6,000 passionate ornithologists, naturalists, conservationists, researchers, scientists, enthusiastic citizen scientists and passionate birders (like myself) How do we know you the AOS leadership isn’t planning to ram forward your pilot program and future endeavors with out the inclusion of concerned and diverse groups of people? Actions speak louder than words.

Just one more thing. I think Wilson’s Warbler is a perfect name. When I see one in the field or in a book, the bird reminds me of what Alexander Wilson actually looked like! (Yes, I am one of those people that is passionate about birds, ornithological history and likes to read about some of the folks for whom a particular bird was named after) If you look at the famous portrait of him the top of Wilson’s head and hair looks like a black cap. He has black beady eyes and a long pointed nose. The bird, Wilson’s Warbler has a black cap, black beady eyes and a long pointed bill! Perfect!

I am happy to see the Pilot Project treating 6 eponymous names individually, and I trust that this process will go well, adding impetus to forge ahead with our traditional case-by-case considerations of all other eponymous et al. English names that may warrant a change.

Is there any discussion of removing “American” from the names of the American Three-toed Woodpecker, American Dipper, American Robin, American Avocet, and others, as well as from the society name itself given that the moniker ‘America’ is an honorific for the 15th-century Florentine cartographer Amerigo Vespucci.

wow, this is the first time I have heard about this.

If democracy is still important, I think the AOS should take into account what most birders and ecologists think about this. This change should be decided by a popular vote. Maybe it would be good using eBird to allow users to vote for this. The AOS states that they are doing this to include more people. However, by taking this decision without a popular vote they are not including non-ornithologists.

This has become a divisive issue in the birding community. Support for retaining some eponymous bird names should not infer racism. Some of those in support of removing all eponymous names imply their opponents are guilty of prejudice. I have been a birder for many years and I have seen very few instances of racist behavior.